The vaccine by Edward Jenner and the sculpture by Giulio Monteverde

Part 1

Lady Mary Wortley Pierrepont, wife of the English ambassador to Istanbul Lord Montague, fell ill with smallpox in 1714 and managed to recover.

She had followed her husband to Turkey, where she had seen some women infect themselves and her children with smallpox pustule serum. These became very slightly ill, and yet became immune to smallpox.

The Lady, of modernist ideas, did not hesitate to inoculate the disease to her children, with excellent results, and she tried to publicize the method in England, but she found strong resistance among doctors and ecclesiastics. But in many parts of Europe this technique was accepted and the kings of Denmark and Sweden, the dukes of Parma and Tuscany and the Tsarina Catherine II were vaccinated.

But she found that a small percentage of the vaccinated took smallpox severely, and died from it.

Edward Jenner (1749 – 1823) in his youth was infected with smallpox, which he overcame, but which marked him deeply. Due to this disease, he was not accepted at the University of Oxford, where he would have liked to attend medicine courses.

He managed to become a pupil and assistant of a country doctor, Dr. Ludlow, who taught him the profession. He then went to London where he attended the hospital under the guidance of Dr. Hunter.

Jenner saw that farmers who milked cows that had caught cowpox, other than human pox, got sick, but not fatally. And he did this experiment: he took serum from a cowpox patient and inoculated it into a child who became slightly ill; shortly thereafter he inoculated human smallpox serum to him, and the child did not get sick. He discovered that cowpox immunized against human smallpox without causing serious or fatal symptoms.

Jenner published these findings and despite strong medical and religious opposition, this practice was followed across much of Europe. In 1803 the Jenner Institute was opened in London.

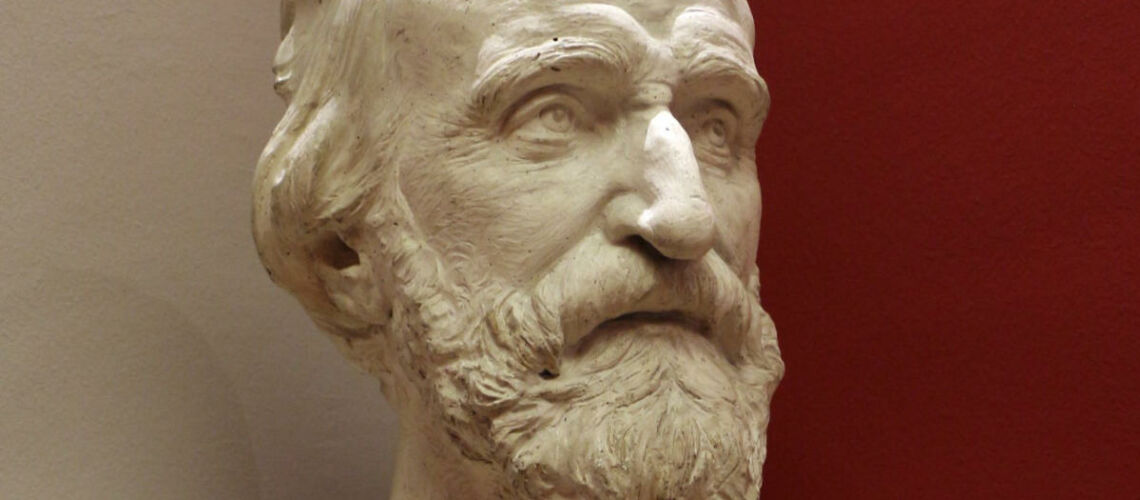

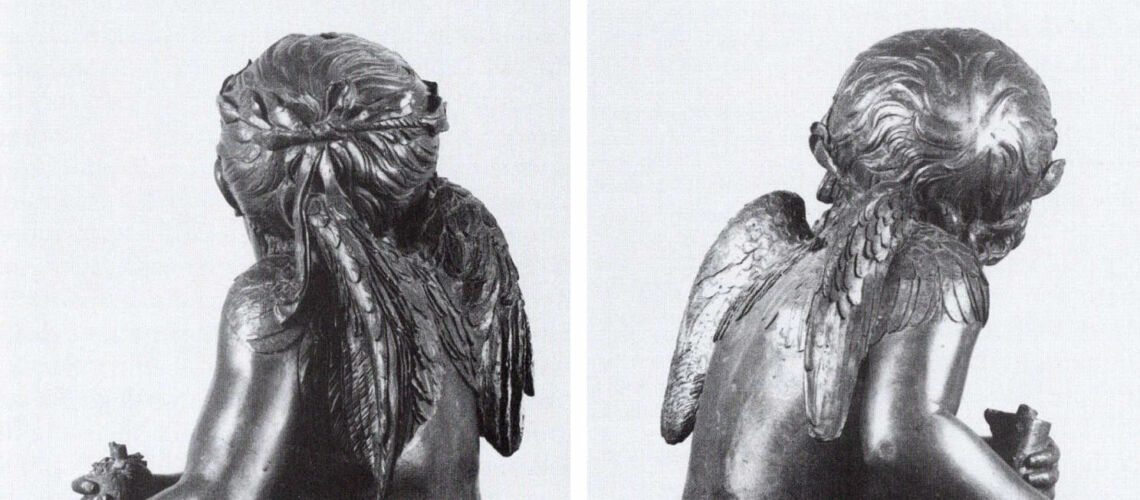

The Piedmontese sculptor Giulio Monteverde

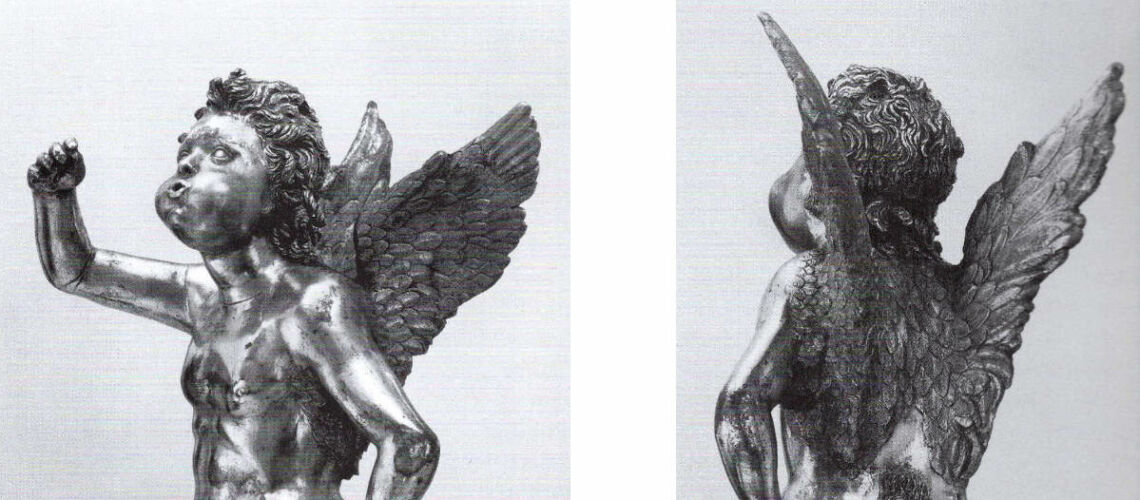

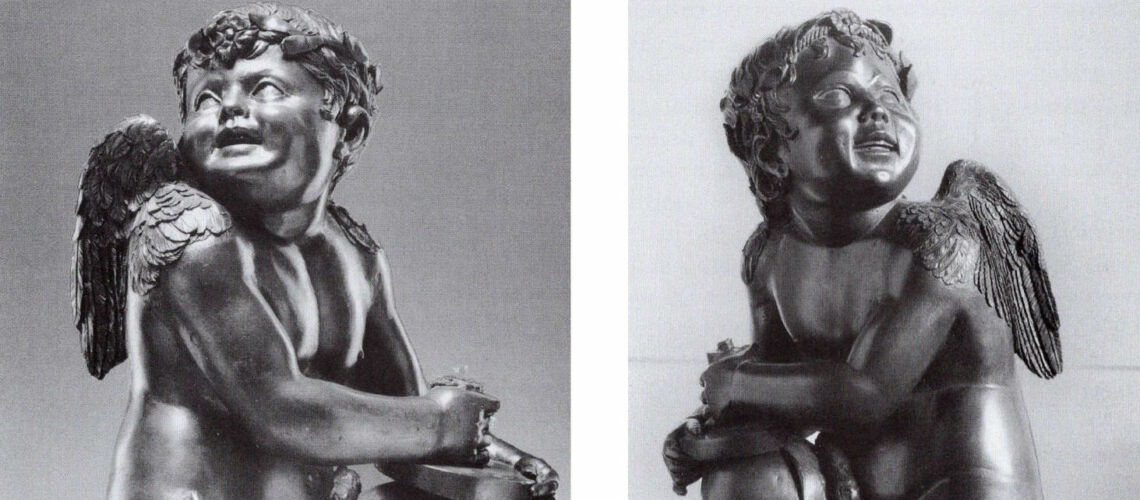

in 1873 modeled the sculpture “Jenner inoculating the smallpox vaccine to the son”; he cast a bronze original and carved also a marble original, who won the gold medal at the Universal Exhibition in Vienna. It is an important and beautiful work that shows Jenner while, focusing on the responsibility he takes, inoculates the smallpox vaccine on a child.

Dr. David B. Agus M.D. of the “Lawrence J. Ellison Institute for Transformative Medicine of USC” in Los Angeles, asked the Ferdinando Marinelli Foundry in Florence to cast two bronze copies of the sculpture taken from the original, and therefore to find out where to find the original in plaster of the author from whom these copies could be made.

It turned out that the original plaster model is kept at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Genoa together with the marble original.

The Foundry obtained from Dr. Francesca Serrati, director of the Museum, to allow those in charge of the Lawrence J. Ellison Institute for Transformative Medicine of USC to make a mould and create a life-size model.

The very faithful model has been delivered to the Ferdinando Marinelli Foundry in Florence, which has begun to create by lost wax casting two bronze replicas of the sculpture.