Donatello and the Putto in the scultpture

Part VII

Another important bronze casting by Donatello is that of Judith and Holofernes in natural size (236 cm with a bronze base) today in front of the Palazzo della Signoria in Florence, but probably commissioned by the Medici for the courtyard of their building. The heroic Jewish Judith is about to cut off the head of Holofernes, general of Nebucodonosor, completely drunk, thus saving his people.

On the pillow in which Oloferne is seated there is the signature of Donatello OPVS – DONATELLI – FLO, and also the writing EXEMPLUM – SAL – PVB – CIVES – POS- MCCCCXCV, a writing that was added when the statue was placed outside the Palazzo della Signoria in 1495.

But by August 1464, when it was still in the Medici palace, there were two other writings on the basement that had been lost: “Regna cadunt luxu surgent virtutibus urbes caesa vides humili with superb manu”, that is: “The kingdoms fall by lust, rise again thanks to the virtues: here is the neck of pride cut from the hand of humility “. And between the years 1464 and 1469 Piero de ’Medici added a second inscription: Regna Cadunt / Salus Publica / Petrus Medices Cos. Fi. Libertati simul et fortitudini hanc mulieris statuam quo cives invicto constantique animo ad rem pub. redderunt dedicavit, that is “Piero son of Cosimo dedicated the statue of this woman to that freedom and fortitude conferred on the republic by the unconstrained and constant spirit of the citizens.” Everything suggests that for Donatello and his peers Giuditta, heavily clothed and covered, represented continence that overcomes pride and lust symbolized by Holofernes limply seated on a pillow. And, by definition, the republic, like Florence and Venice, was compared to ancient Greece and Rome and opposed to tyrannical states like Milan, the enemy of Florence. Holofernes was the general of a totalitarian monarch. Giuditta, savior of the freedom of Israel, was related to the resistance of the Florentine Republic against the tyranny of the Visconti of Milan.

On the triangular base of the statue there are three bas-reliefs based on the cherubs. On the first one winged, naked or semi-naked putti of different ages, they harvest and carry the grapes in the baskets; below is a lying drunk figure, wearing a mask and holding a jug. It is a Bacchic scene, as in the feast in honor of Dionysus in ancient Greece, where they acted masked actors.

On the second bas-relief two putti crush the grapes inside a crater, also decorated on the edge with putti and garlands. A putto drinks directly from the crater, another pulls up his robe, two are lying down drunk.

On the third bas-relief a putto sitting on Dionysus’s lap kisses him, others play horns and dance.

The three scenes represent a bacchanal and its deleterious effects, and have nothing to do with the Christian scenes of harvest and wine production used in a Eucharistic sense. They refer to the drunkenness of Holofernes. In the “Republica” Plato writes that drunkenness transforms man in a tyrant, like the tyrannical Eros, a neo-Platonic interpretation followed by Donatello.

Also on Judith’s dress, putti appear: on the front of the bodice two naked winged cherubs support the circle, on the other side two more putti with desperate faces are at the side of a vase, others behind, others on the right cuff.

Unlike those of the bas-reliefs, the cherubs on Judith’s dress symbolize her victory.

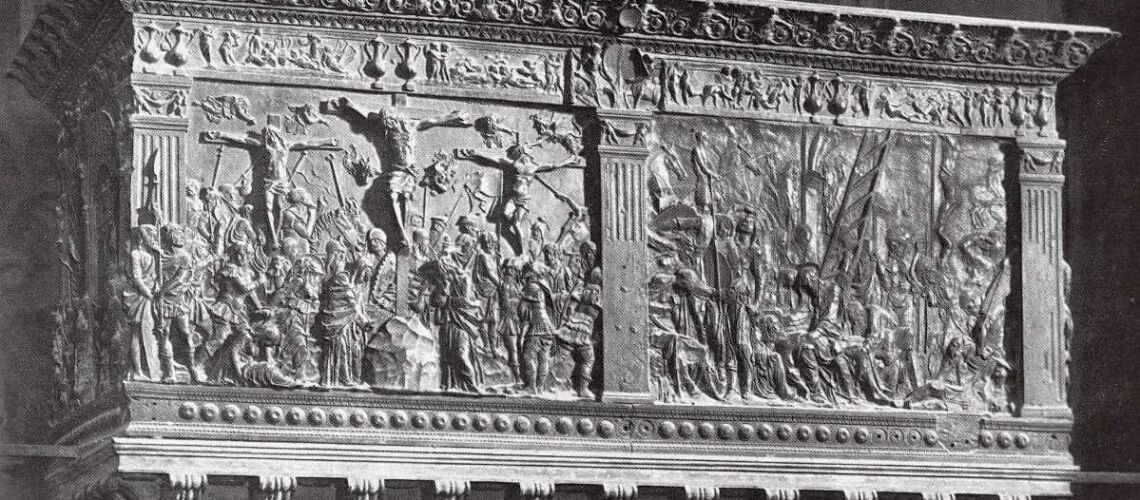

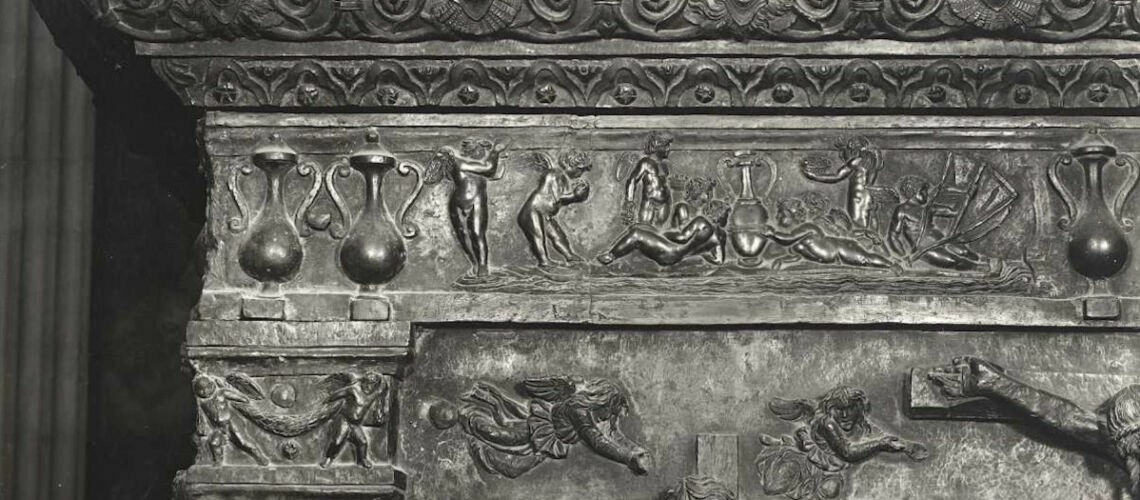

Donatello’s last masterpieces are the two lost wax bronze pulpits for the church of San Lorenzo in Florence, executed after 1460. It is likely that at the time of his death in 1466 they were completed by his helpers Bartolomeo Bellano and Bertoldo of Giovanni, the latter also a friend of Lorenzo the Magnificent. They have suffered various vicissitudes including the arrangement on the columns at the beginning of the ‘500 and a subsequent reassembly in the middle of the’ 500. In both of them Donatello created a narrow trabeation band in which the small putti appear, and it is the first time that this type of decoration reappears after the classical era, in fact Donatello was inspired by the Roman sarcophagi. In these two pulpits the putti return to be secondary elements that comment on the scenes below, with Bacchic dances and references to the grape harvest and wine.

The Pulpit of the Passion

It consists of seven scenes: Prayer in the Garden of Olives, Jesus by Pilate and Caiaphas, Crucifixion, Compianto, Burial (the two bas-reliefs of the Flagellation and of St. John the Evangelist are made of wood and date back to the ‘600). In the trabeation of this pulpit the putti are Bacchic because they refer to the work of the vineyard and the wine but are not drunk, and symbolize, in the context of the Passion of Christ, the Eucharist. In ancient times the cult of Dionysus promised a life after death, and its rites included drinking wine. For the Neo Platonists of the Renaissance, Dionysus prefigures Christ with his promise of salvation, given to the initiated through participation in the Christian Mass with the offering of bread and wine. There are also some parallels in the life of Dionysus-Bacchus and that of Christ: they both had a miraculous birth, both performed miracles with wine, both have grapes as attributes, in both religions there are aspects of suffering, death and life in the afterlife.

We see another connection to the scene of Jesus in the Olive grove in two cherubs to the right of the trabeation kissing foreshadowing the traitor kiss of Judas.

In the bas-relief of the Crucifixion one of the putti on the left is navigating holding a sail.

Sailing putti are present in the ancient frescoes and mosaics as a symbol of the passage of life to the afterlife, and in the Crucifixion the passage from life to the death of Christ. In that of the Burial, in addition to playing with grapes, the Eucharistic symbol, two cherubs play musical instruments and two embrace to console themselves.

and also on the capitals of the pillars, putti holding garlands appear, just as putti appear on the capitals of the Crucifixion and of the Lamentation.

Others are placed above the capitals of the columns of Christ before Caiaphas and Pilate.

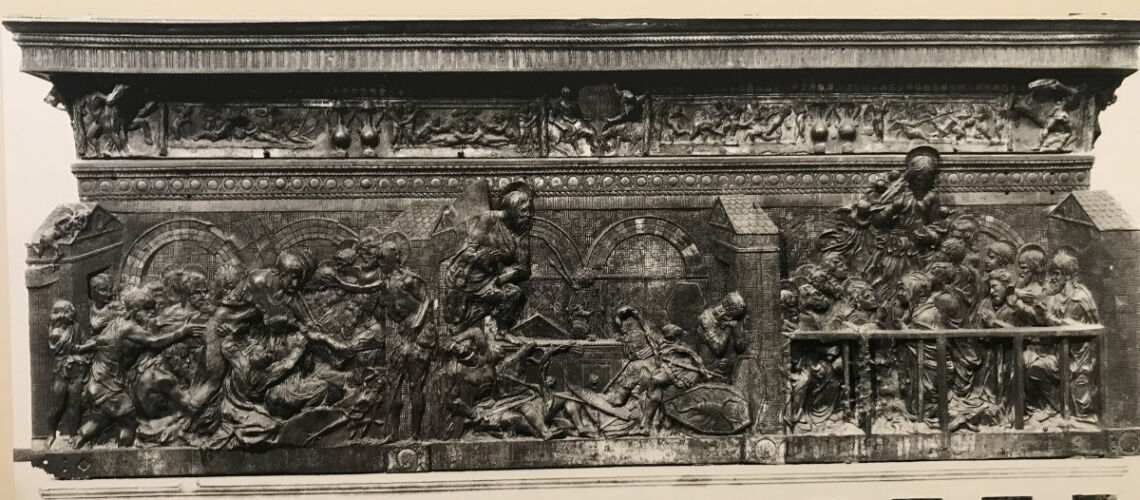

The pulpit of the Resurrection

it is composed of eight scenes: The Pious Women at the Sepulcher, Descent to Limbo, Resurrection, Ascension, Pentecost, Martyrdom of San Lorenzo, Christ derided, St. Luke the Evangelist, and also this the entablature with cherubs.

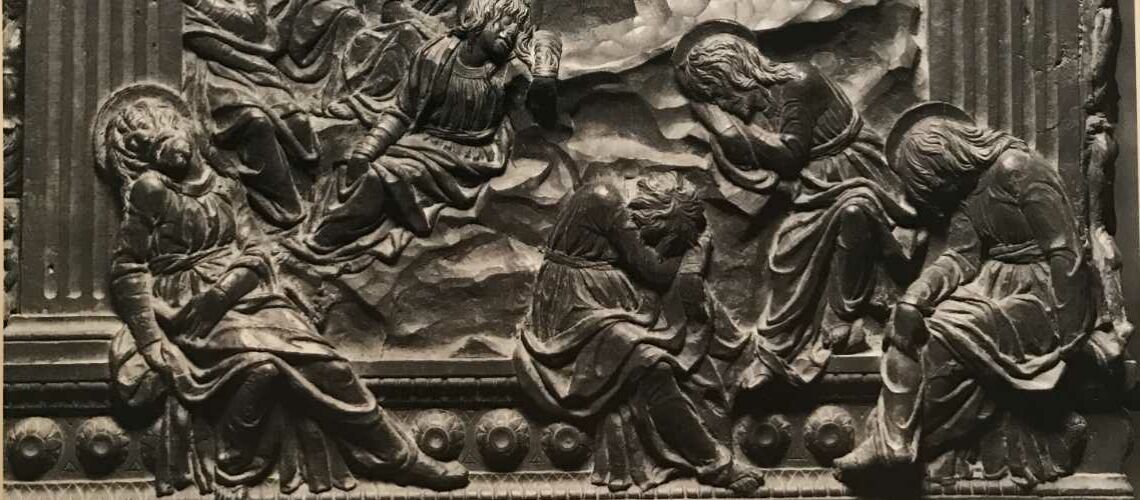

In the Pious Women at the Sepulcher a putto is sleeping, in harmony with the two soldiers on the far right of the bas-relief.

Within the scene of the Ascension winged putti fly attached to the Christ’s mantle

and in the trabeation of the putti they are raising a fallen herm, and on the left others raise the statue of a putto with the cornucopia. They could both be symbols of Christ’s resurrection.