Michelangelo, the Madonna of Bruges

In 1501 Michelangelo had returned to Florence from Rome, and was working on the execution of the great David. Through the banker Jacopo Galli, his friend and guarantor, the two Mouscron brothers, Flemish fabric merchants, clients of Galli’s bank, commissioned Michelangelo to create the sculpture of a Madonna and Child for their chapel in the church of Our Lady of Bruges.

|

Church of Our Lady of Bruges |

Church of Our Lady of Bruges, facade |

|

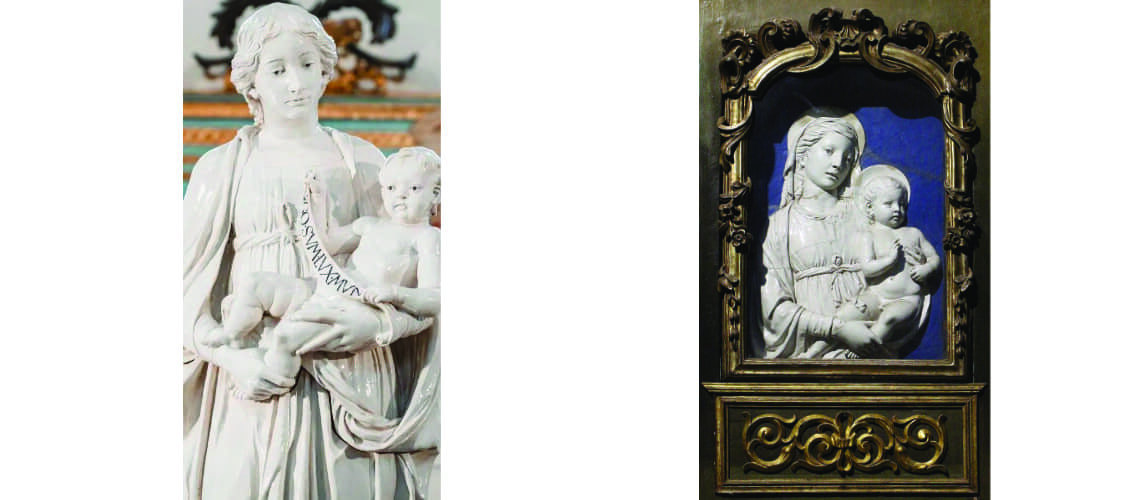

Michelangelo’s Madonna inside the Church of Our Lady of Bruges |

Michelangelo’s Madonna in the niche inside the Church of Our Lady of Bruges |

The agreed fee was 4,000 florins, a very high sum promised to Michelangelo probably to convince him to find the time to carry it out even though he was working on other works; they were given to him in two payments between 1503 and 1505.

This would also be confirmed by the fact that Michelangelo sculpted it, keeping it hidden until he embarked in Viareggio towards Flanders around 1506. Giovanni Balducci in Rome on 14 August 1506 wrote to Michelangelo:

…Michelagnolo carissimo, resto avisato chome Francesco del Puglese avrebbe chomodità al mandarla a Vioreggio, e da Vioreggio in Fiandra…

[…My dearest Michelagnolo, I am advised that Francesco del Puglese would be happy to send you to Viareggio, and from Viareggio to Flanders…]

The Madonna of Bruges

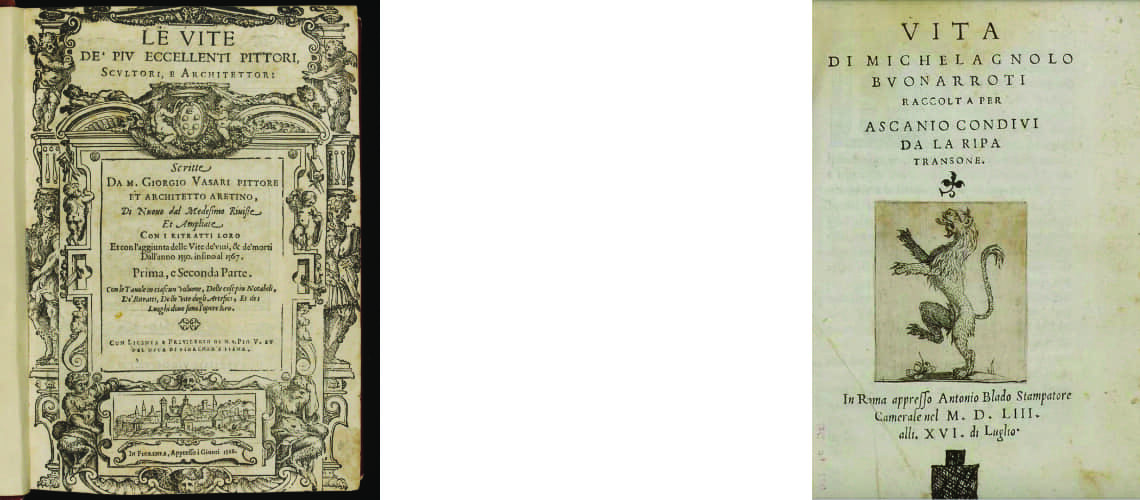

Not even his biographers knew exactly what it was: Condivi thought it was a bronze sculpture, Vasari thought it was a round one.

Michelangelo wrote to his father in this sense:

…Prego voi che duriate un pocho di fatica in qusta due cose, cio è in fare. Riporre quella cassa [contenente la Madonna] al coperto in luogo sicuro; l’altra è quella nostra Donna di marmo, similmente vorrei la faciessi portare costì in casa e non la lasciassi vedere a persona…

[…I ask you to make a little effort in these two things, that is, in doing. Place that crate [containing the Madonna] indoors in a safe place; the other is that Marble Woman of ours, similarly I would like to have her brought into the house and not let anyone see her…]

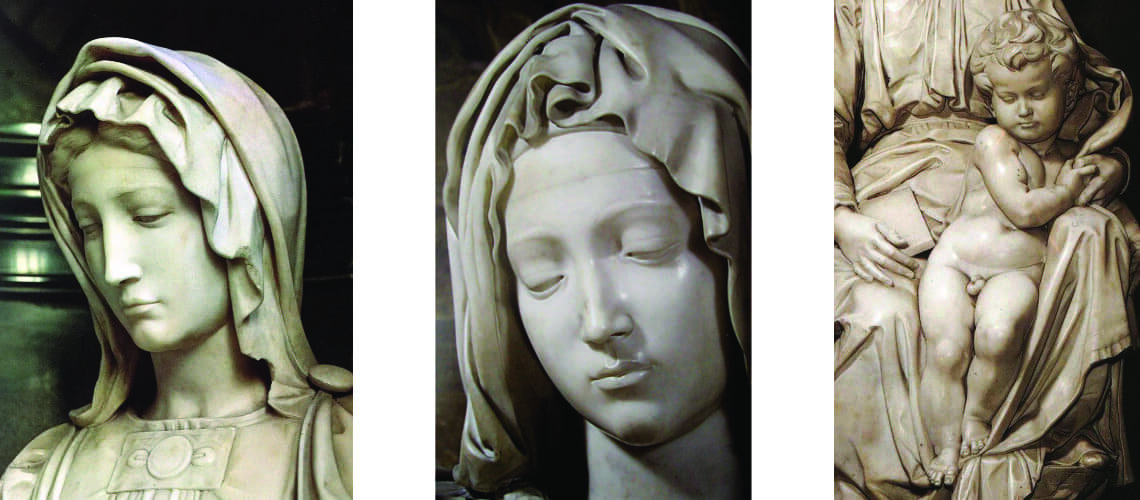

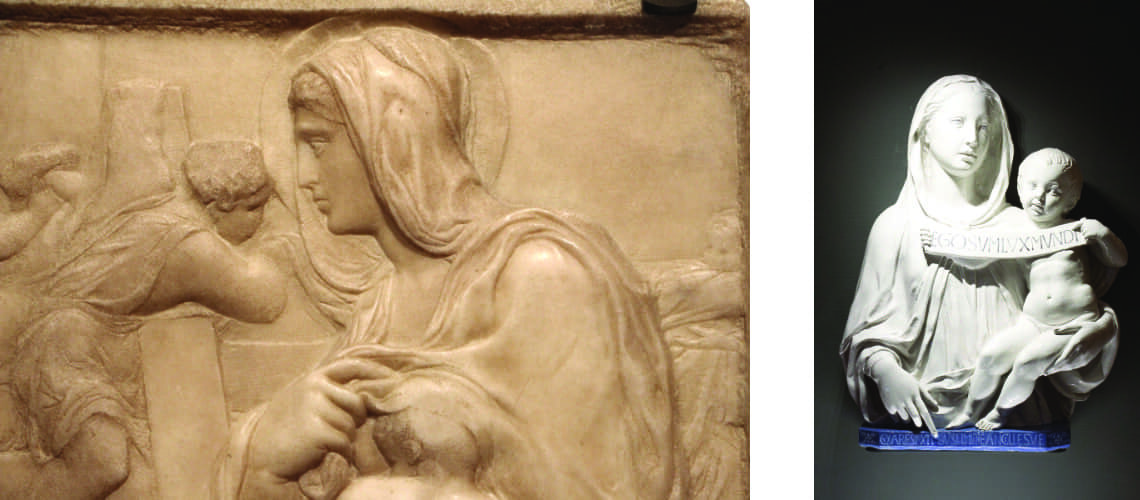

While he was sculpting it, he still had his previous Vatican Pietà in mind: this can be understood in a particular way from the similarity of the faces of the two Madonnas, both with their gaze turned downwards, and the veil on their heads. The Child’s body presents a twist that seems to be due to his sliding on the Mother’s dress while he holds on to his left hand and leans with his feet on the edge of her dress, as if he wanted to get off her lap.

The Madonna, on the other hand, is perfectly still and absorbed in the thought of the terrible end that her Son will meet.

|

Michelangelo, Madonna of Bruges, detail of the Madonna |

Michelangelo, Vatican Pietà, detail |

Michelangelo, Madonna of Bruges, detail of the Child |

The Madonna was taken and transported to Paris by Napoleon, and was returned in 1815. In 1944 it was stolen by the Nazis and taken to Germany, it was discovered in 1946 hidden in a mine in Altaussee in Austria and was brought back to Bruges.

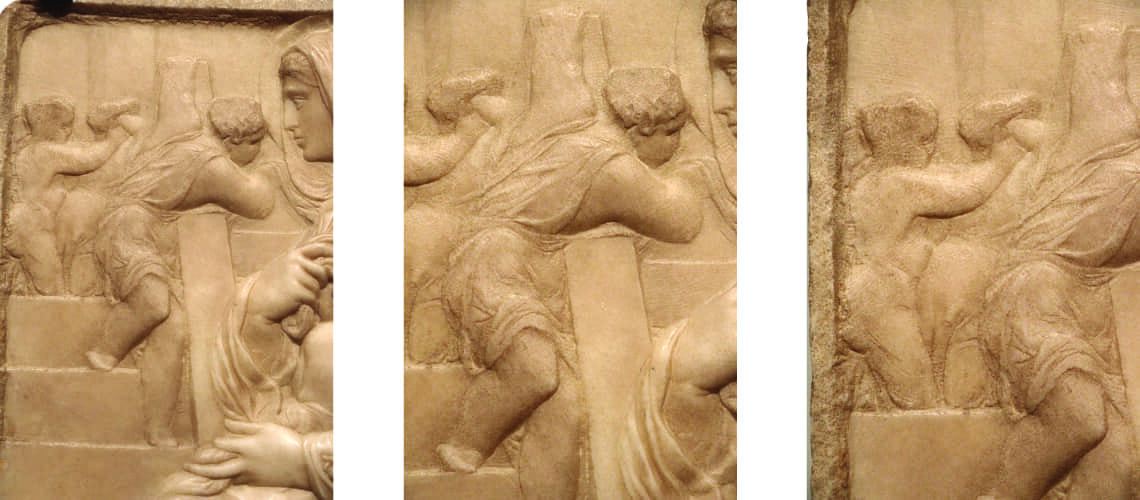

Posthumous original statuary bronze casting from a mould made on the original by the Ferdinando Marinelli Artistic Foundry of Florence