Giambologna and the rape of the Sabines - Part II

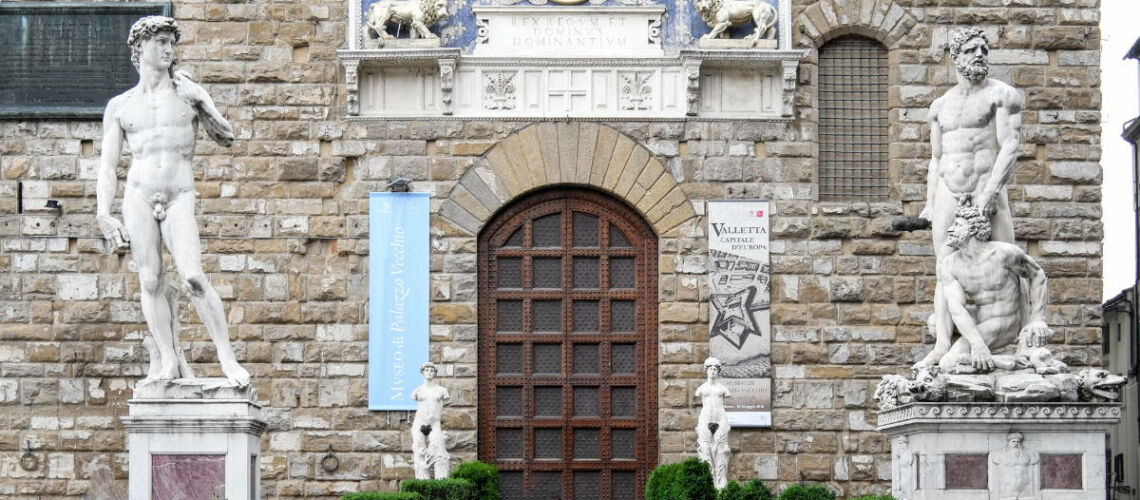

The David and the Hercules

It was in 1504 with Michelangelo‘s gigantic marble David placed outside the door of Palazzo della Signoria, now Palazzo Vecchio, that the government of Florence allowed the taboo of nudity seen from the front to be completely overcome, so much so that it was exhibited in such a public important place.

And in fact in 1534 the naked David was flanked by Baccio Bandinelli’s Hercules subduing Cacus. Duke Cosimo I of the Medici had in fact chosen as his symbol no longer David, as had been done first by the Medici of the Cafaggiolo branch, then by the Florentine republic, but precisely by Hercules.

| Michelangelo’s David (19th century copy) outside Palazzo Vecchio | Hercules and Cacus outside Palazzo Vecchio |

Perseo, Giuditta e Oloferne

In 1554, the bronze of Perseus with the head of the Medusa by Benvenuto Cellini, also naked and with his genitals visible, was placed in the Loggia dei Lanzi; it had been chosen as a pendant of Donatello’s group of Judith and Holofernes previously seized from the garden of the Palazzo Medici in via Larga (now via Cavour) in 1494 as a trophy of the republican victory.

With the Medici’s return to power, the group was not removed, because the new rulers wanted them to be identified with the ancient Jewish heroine Judith and their republican adversaries identified with Israel’s enemy Holofernes.

Perseus by Benvenuto Cellini, Loggia dei Lanzi, Florence

Only in August 1583 was the bronze of Judith and Holofernes moved to make room for Giambologna’s colossal marble statue with three naked figures of both sexes entwined with violent sensuality. However, the positioning under the arch of the Loggia dei Lanzi, in the same point as the Judith, created limitations on the possibility of walking around the work, which was created to be seen at 360°.

| Judith and Holofernes outside Palazzo Vecchio, Florence | Rape of the Sabines, Loggia dei Lanzi, Florence |

The model

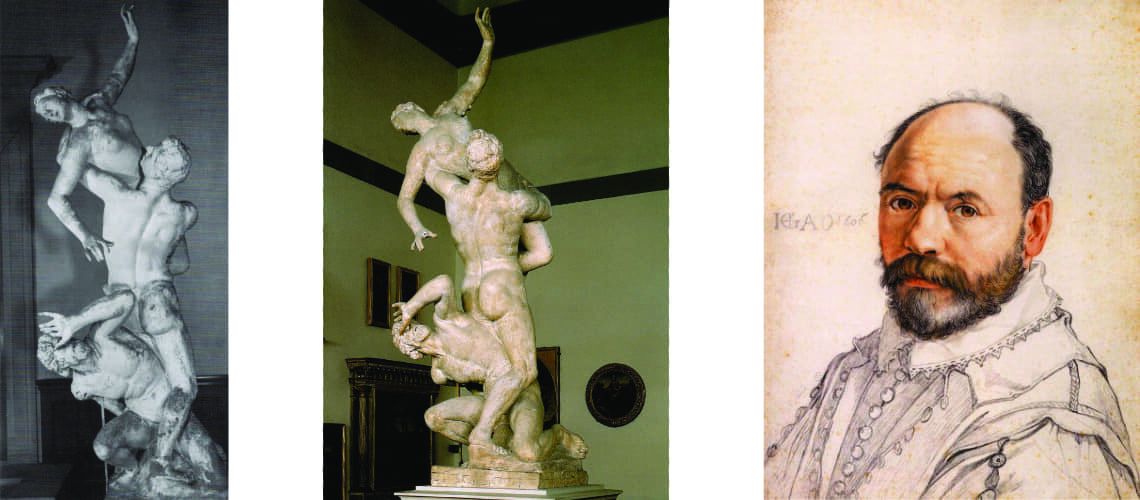

Giambologna, after having created the life-size model, now kept in the Museum of the Academy of Florence, called in a series of assistants for the rough-hewing of the marble, first of all the French sculptor from Cambrai Pierre de Francqueville, whose name was Italianized as Pietro Francavilla.

| Rape of the Sabine Women, model (photo 1932) | Rape of the Sabine Women, model around 1581, Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence | Portrait of Pietro Francavilla, Hendrick Goltzius |

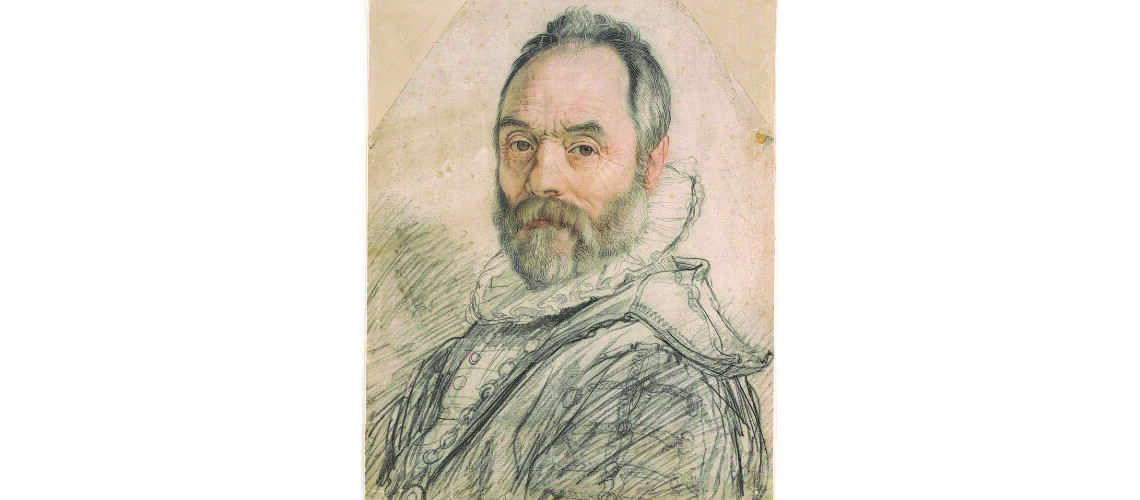

Giambologna, actually the Frenchman Jean Boulogne born in Douai in Flanders in 1529, already renowned in his homeland as a skilled sculptor, probably came to Rome during the Jubilee of 1550 to learn about classical and Renaissance sculpture. He remained there to study for two years, creating a large quantity of sketches and models, most of which, in clay or wax, have come down to us. So much so that when Federico Zuccari painted his portrait in the 1570s, he put one of his sketches in his hand.

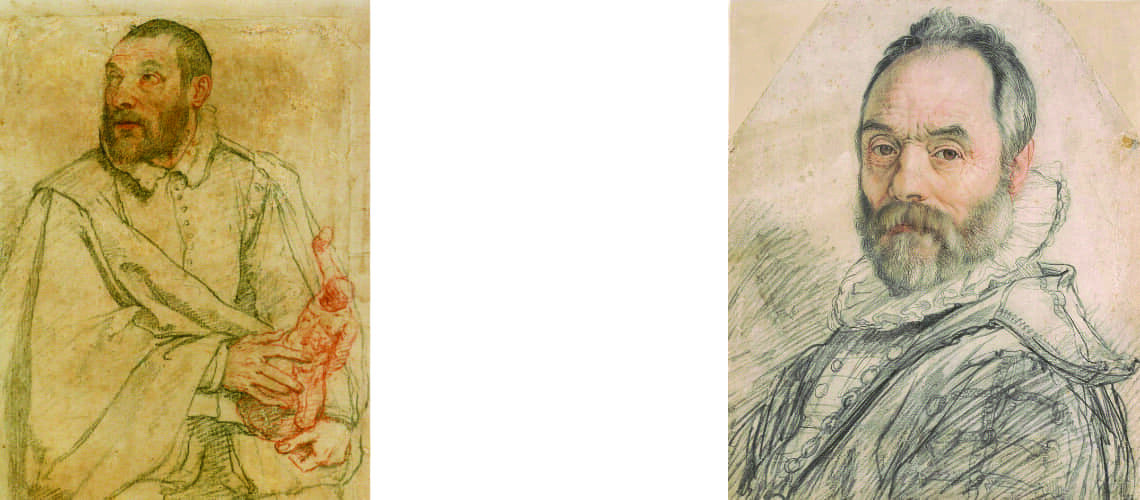

| Giambologna portrait, Federico Zuccaro | Giambologna portrait, Hendrick Goltzius |

Shortly after arriving in Rome, Giambologna went to the almost eighty-year-old Michelangelo to show him a wax model of his that he had worked on with great passion and attention. Michelangelo, leaving him astonished, took him, crushed him, quickly reshaping him into a completely different figure, telling him “Now go first and learn to draft, and then to finish”.

Giambologna developed the idea for a sculpture of a man kidnapping a woman in 1579, and when the Grand Duke commissioned him to create a monumental marble group, the sculptor envisaged a third figure placed at the bottom to ensure stability for the two characters. In fact, he realized that the ankles of the standing man holding the suspended woman were too thin to support himself; he had had the same problem when he had created the Flying Mercury for the Farnese and in fact he was forced to have it cast in bronze, sturdier than marble, to allow the single foot resting on the base to support the sculpture.

| “Rape of the Sabina”, Giambologna, Capodimonte Museum, Naples | Mercury, Giambologna, Bargello Museum, Florence |

He then inserted a third elderly man kneeling as support: we can see from the wax model of the Rape of the Sabine Women how the third kneeling character was modeled and added later.

| “Rape of the Sabina”, wax, Giambologna, Victoria & Albert Museum, London (front) | “Rape of the Sabina”, wax, Giambologna, Victoria & Albert Museum, London (back) |

The success of the sculpture

Giambologna’s monumental work was a huge success, so much so that in 1583 the printer Bartolomeo Sermantelli published a volume with laudatory sonnets and engravings of the sculpture, followed in 1584 by a pamphlet by Grazio Grazi published by Giorgio Marescotti, entitled Rime e versi latini di Gratiamaria Gratii, on the rape of the Sabine women. Sculpted in marble by the excellent Giambologna.

In 1584 Raffaello Borghini, in his Il Riposo, narrates the story of the sculpture from its origin to the success of the work, saying that he himself suggested to Giambologna to title the gigantic group Rape of the Sabines as the most suitable subject for the work.

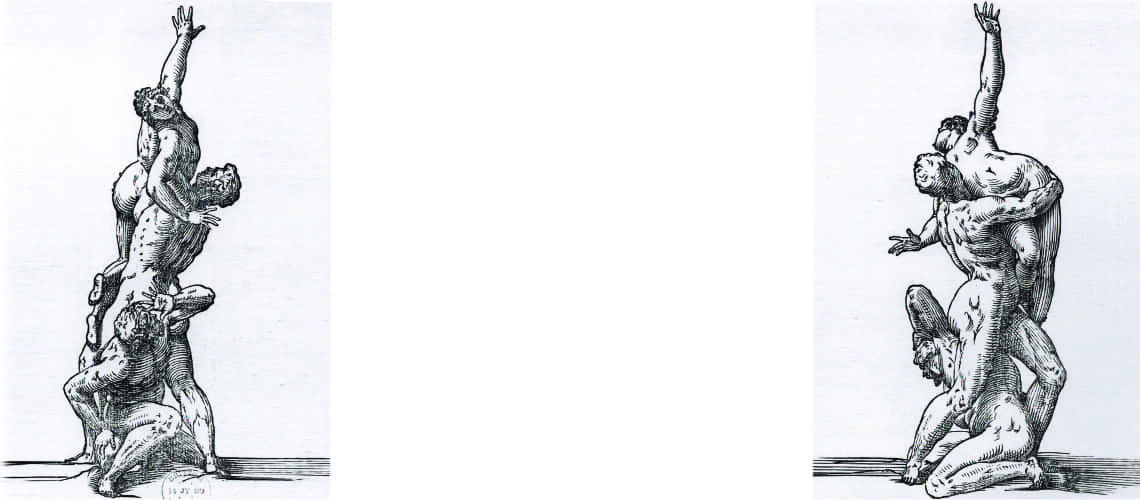

Engravings from the volume “some compositions by different authors in praise of the portrait of Sabina”, British Library, London

Ocean

With the death in 1560 of Baccio Bandinelli, sculptor of the Medici court, a competition was announced for the execution of a large marble Neptune for the fountain to be created at the Palazzo della Signoria. Giambologna participated with a life-size clay model, but the winner was Ammannati.

Giambologna re-used his model, with modifications to transform it into the figure of the Ocean, for a fountain in the Boboli Gardens (now in the Bargello).

When a Flemish painter painted the portrait of Giambologna, he wanted the model of the Ocean to be seen from a window in the painting.

| “Neptune”, Ammannati, Piazza della Signoria, Firenze | “Ocean”, Giambologna, Museo del Bargello, Firenze |

Portrait of Giambologna in his studio, unknown 16th century Flemish painter, Scottish Nat. Gall. Edinburgh

Samson and the Philistine

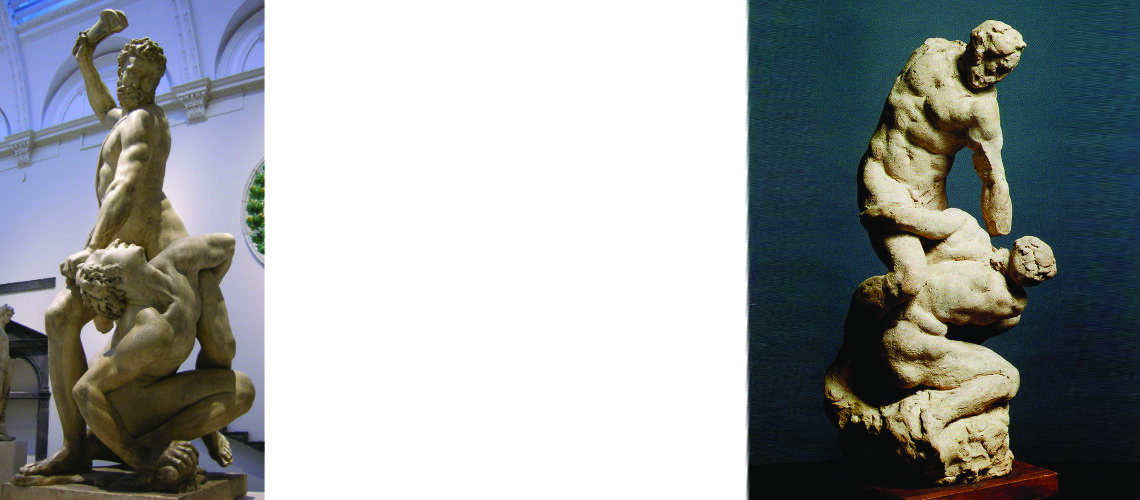

To please his protégé sculptor who had not won the competition for the Neptune fountain, Grand Duke Francesco I dei Medici commissioned him to create a colossal monument of Samson defeating the Philistine, sculpted in marble (kept in the Victoria and Albert Museum). Michelangelo had already set himself in motion when the Florentine Republic asked him for a group of two wrestlers to be positioned symmetrically to the David; the model that Michelangelo created on earth has fortunately come down to us preserved by the Casa Buonarroti.

| “Samson and a Philistine”, Giambologna, Victoria and Albert Museum, London | “Two Wrestlers”, Michelangelo, Casa Buonarroti, Florence |

Bartolommeo di Lionardo Ginori

Interesting is what Filippo Baldinucci writes in the “Notizie de’ professori del disegno” regarding the model that Giambologna had found for his great Roman of the Rape of the Sabine Women: Bartolomeo di Lionardo Ginori lived in Florence, a gigantic man “four whole arms tall” (2 .30 meters), warrior of fortune but pious and kind. Giambologna saw it in the church of San Giovannino dei Gesuiti and began to look at it without stopping. Lionardo kindly asked him what he wanted and Giambologna replied: “I seek nothing more from you than to observe the beautiful, or rather the marvelous, proportion of your figure; and since you so kindly invite me, I will go on to tell you about my need, and it is that since I, who am Gio. I could make some studies from your limbs… Ginori… immediately offered himself to his need; so the Sculptor was then able to personally make the studies and models he made for the figure of that robust young man.”

Giambologna, to thank him, gave him a bronze crucifix made by the well-known foundryman Alberghetti.

Ritratto di Bartolommeo di Lionardo Ginori, Santi di Tito, collezione privata, Firenze