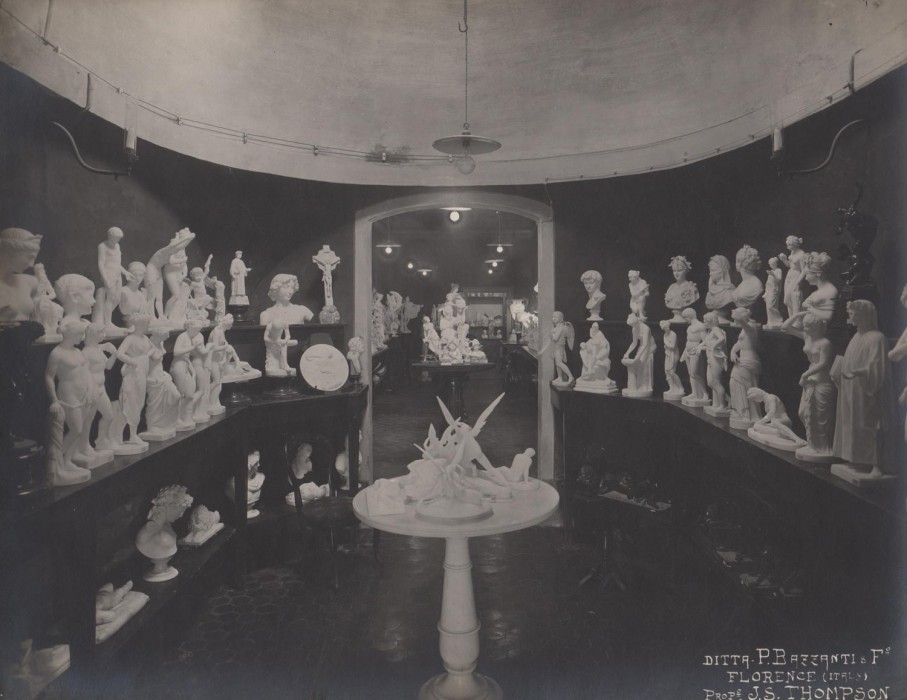

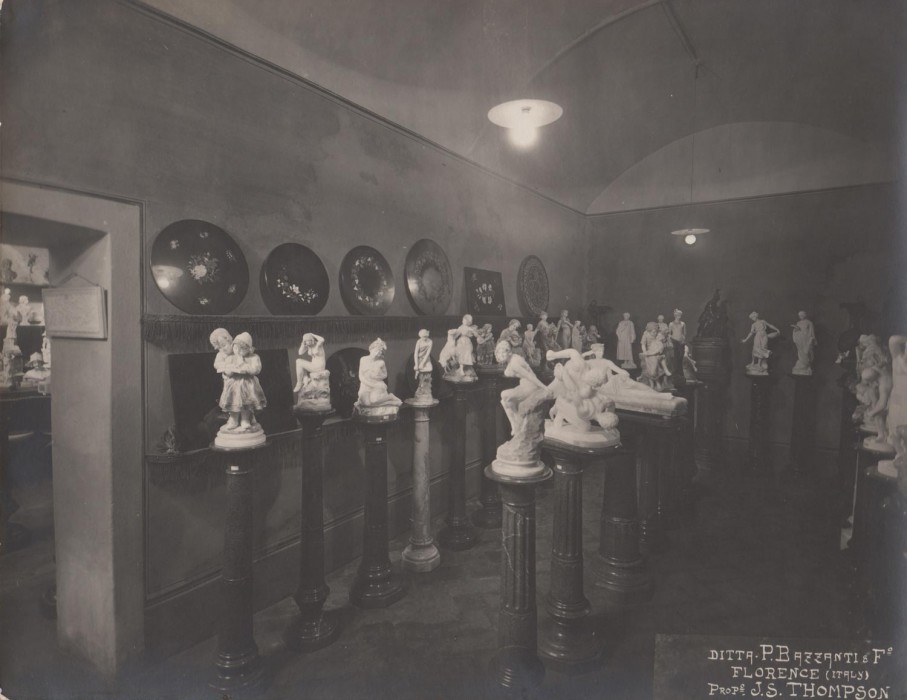

A selection of pictures and postcards with images of works by the Art Gallery Peter Bazzanti and Son and the Ferdinando Marinelli Artistic Foundry of Florence concerning Cart of the Pioneers, the Monumental Staircase in the Vatican, the Holy Door of St. Peter’s Basilica, The Porcellino in Florence, statues and fountains for the Casino of Las Vegas Strip, the Fountain of the Broncos, as well as an overview of the Gallery and the Lungarno Corsini from ‘800 until recent times.

- Vintage Postcards

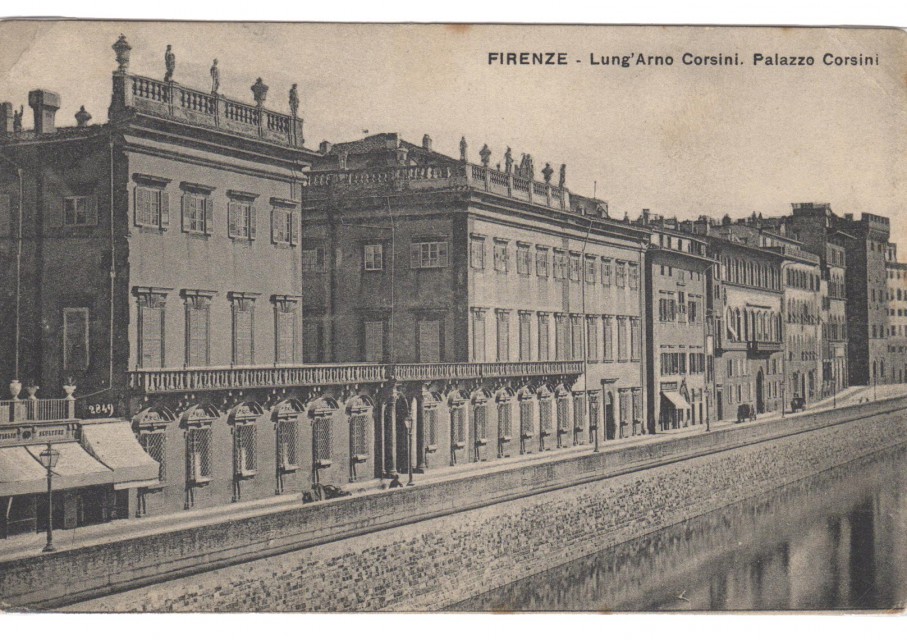

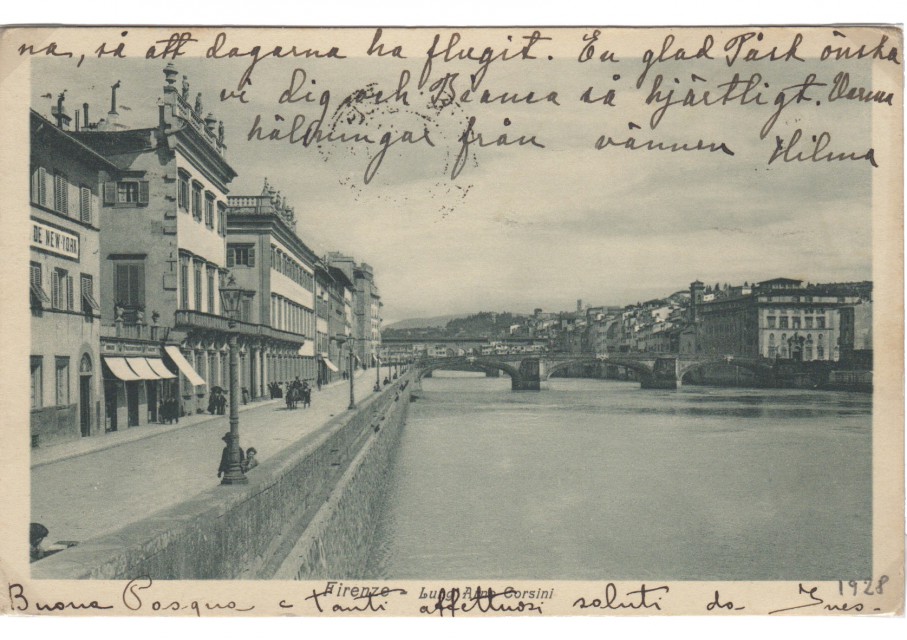

- The Lungarno Corsini

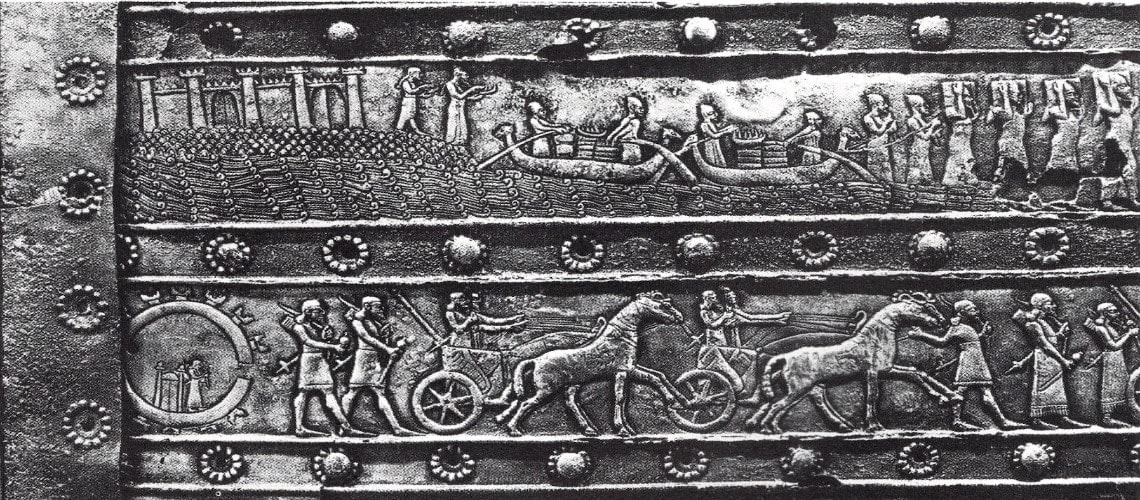

- The Pioneers Cart

- Vatican Museum Stairs

- Chimeras of Arezzo

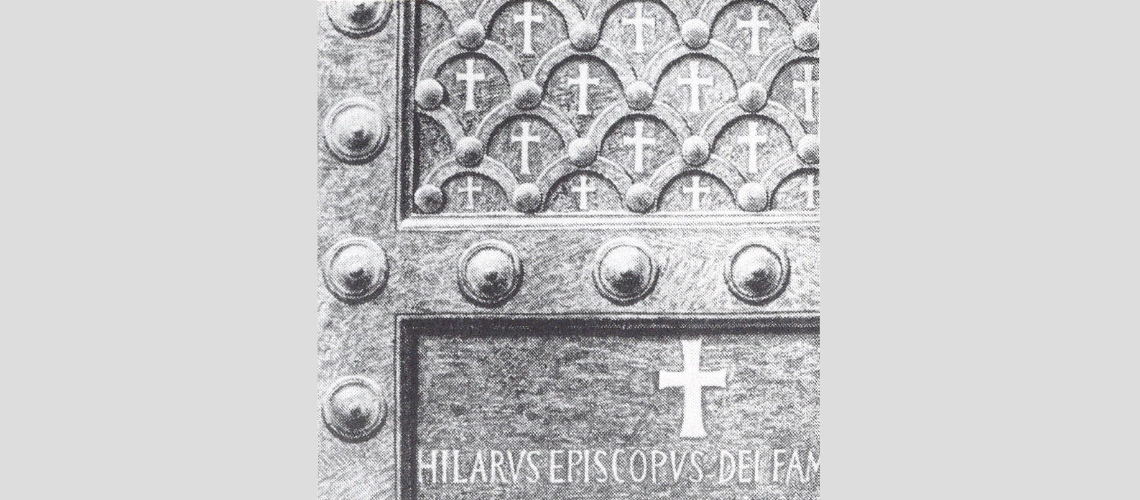

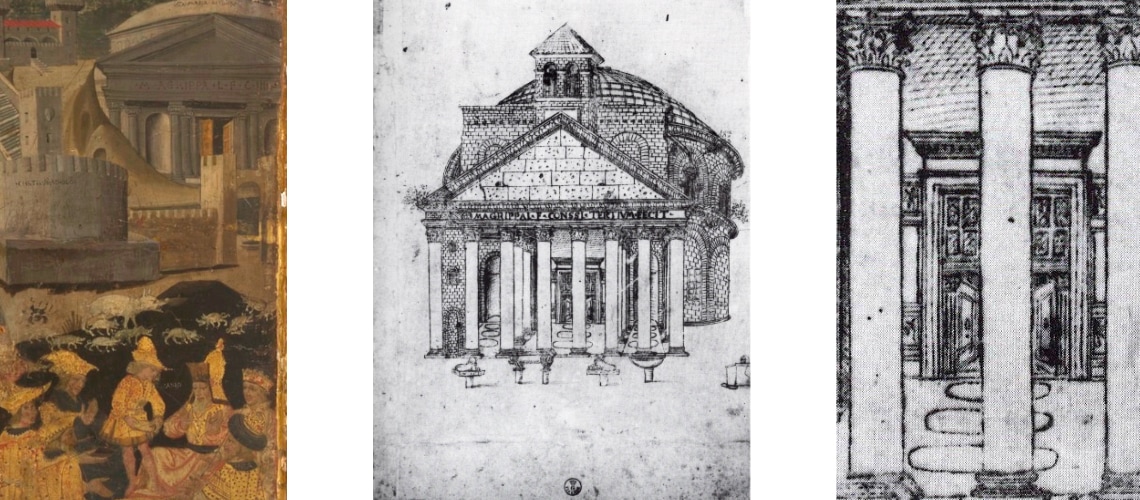

- Siena Cathedral

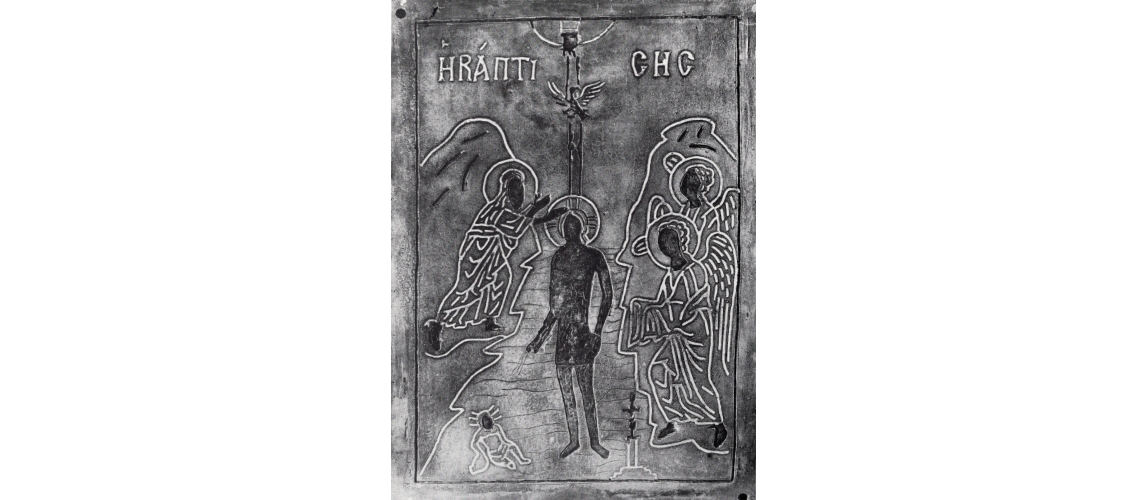

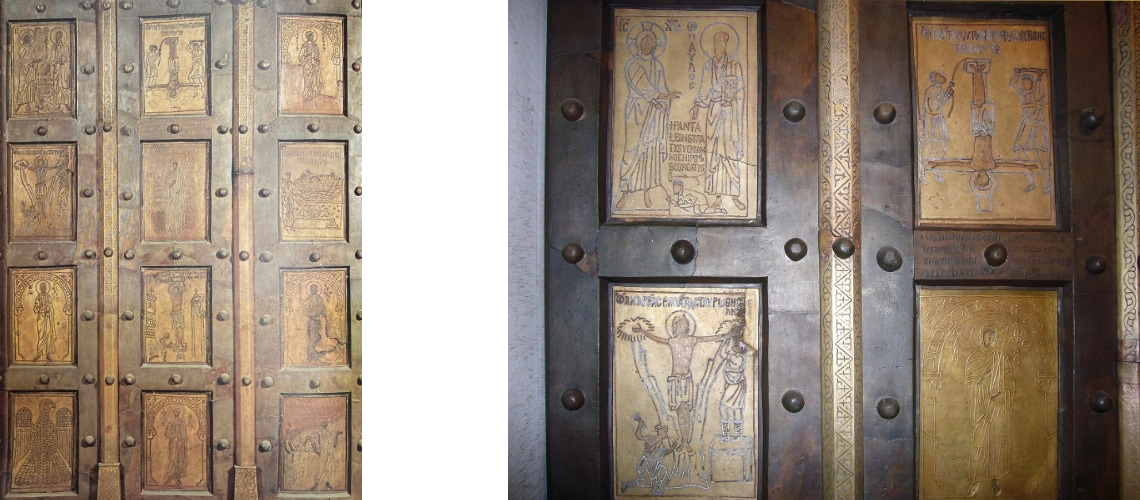

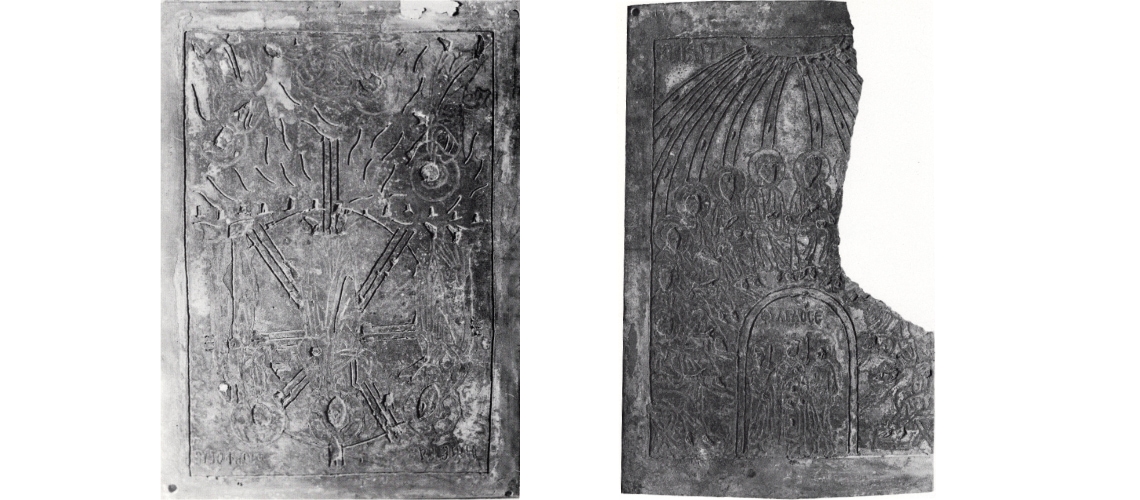

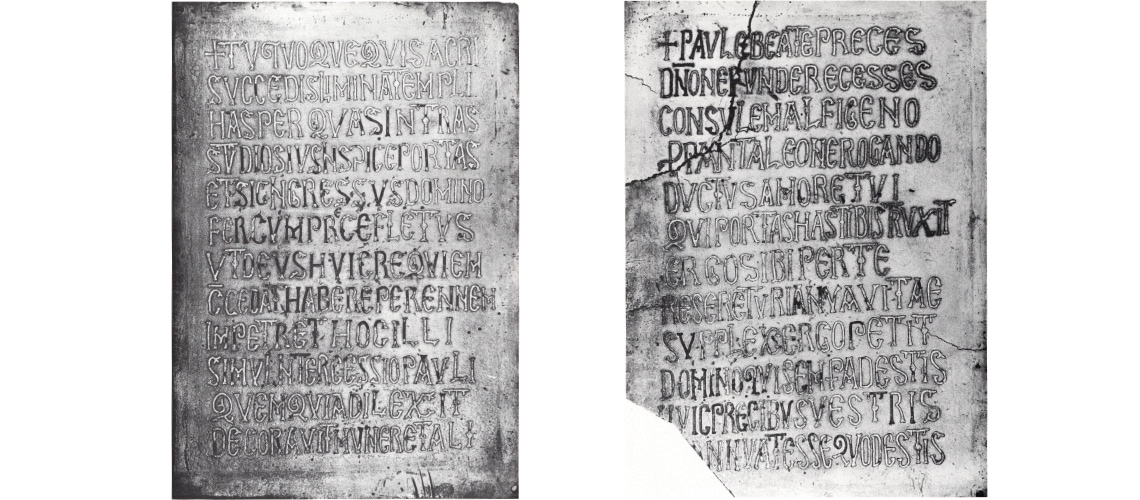

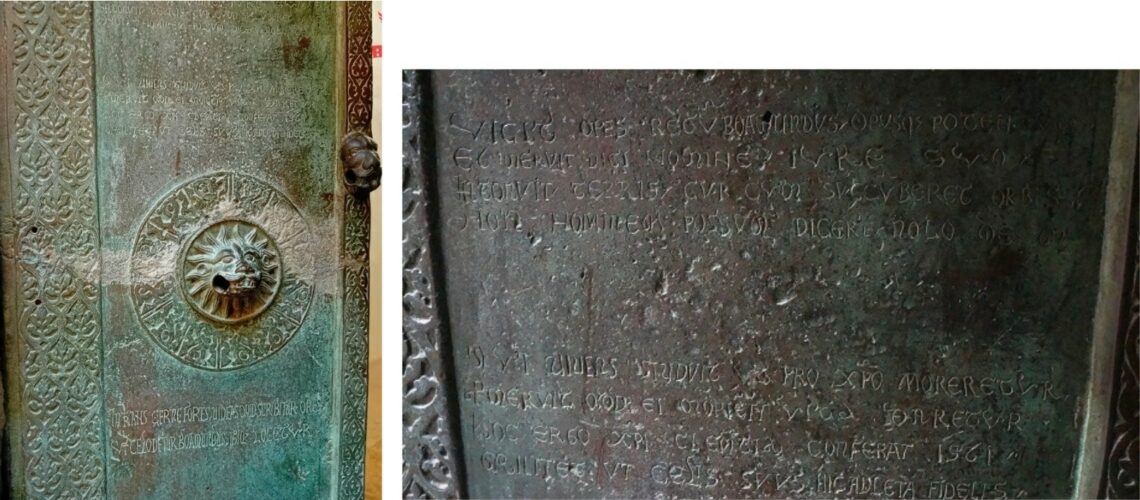

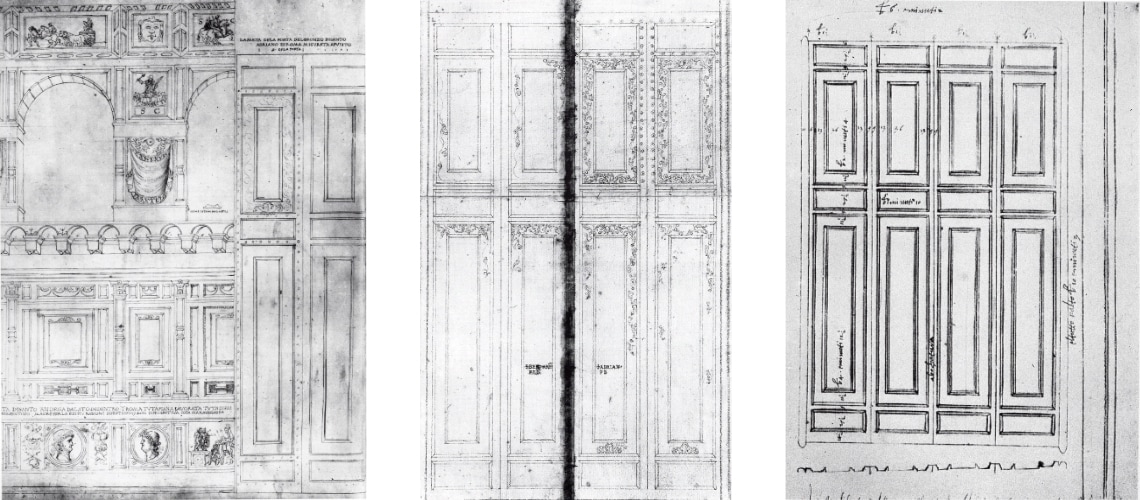

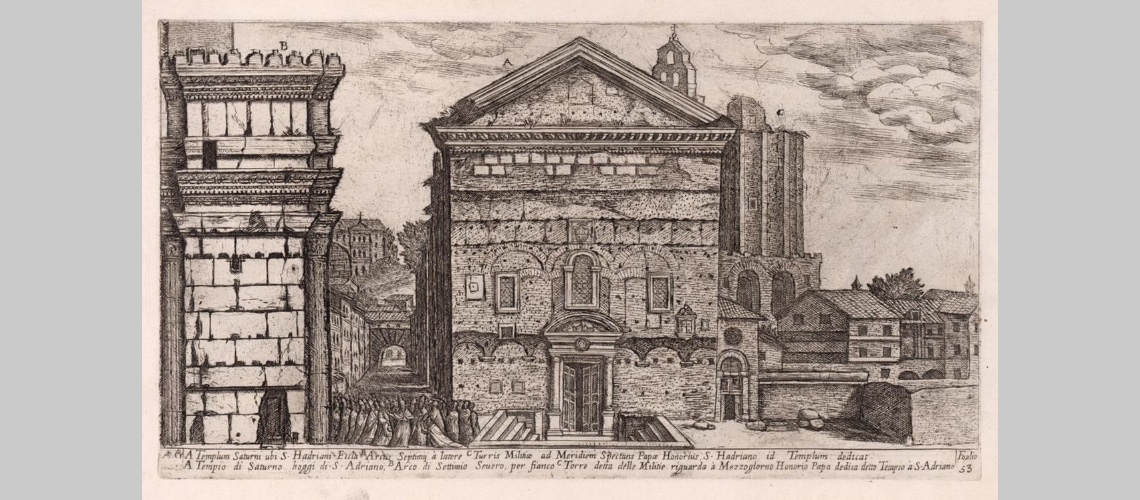

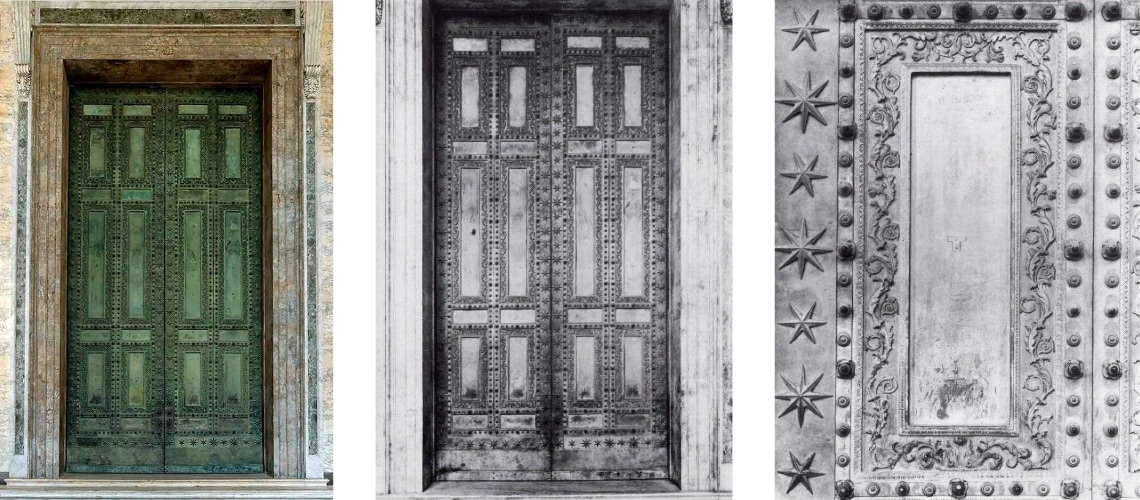

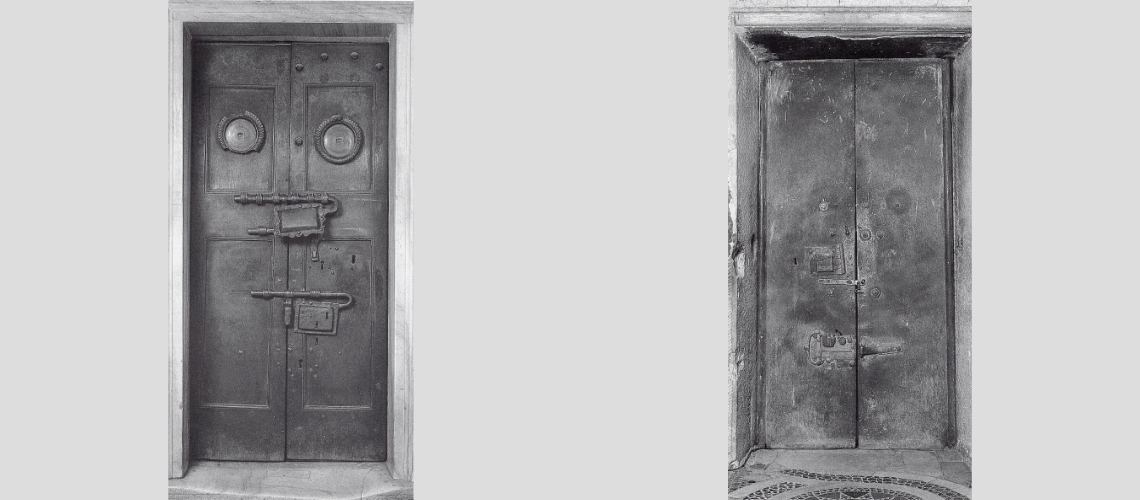

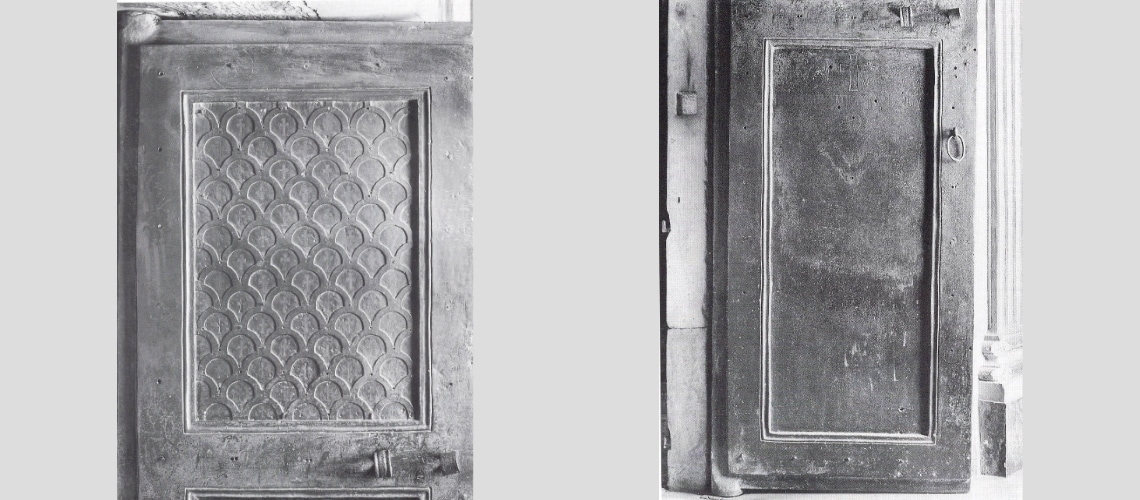

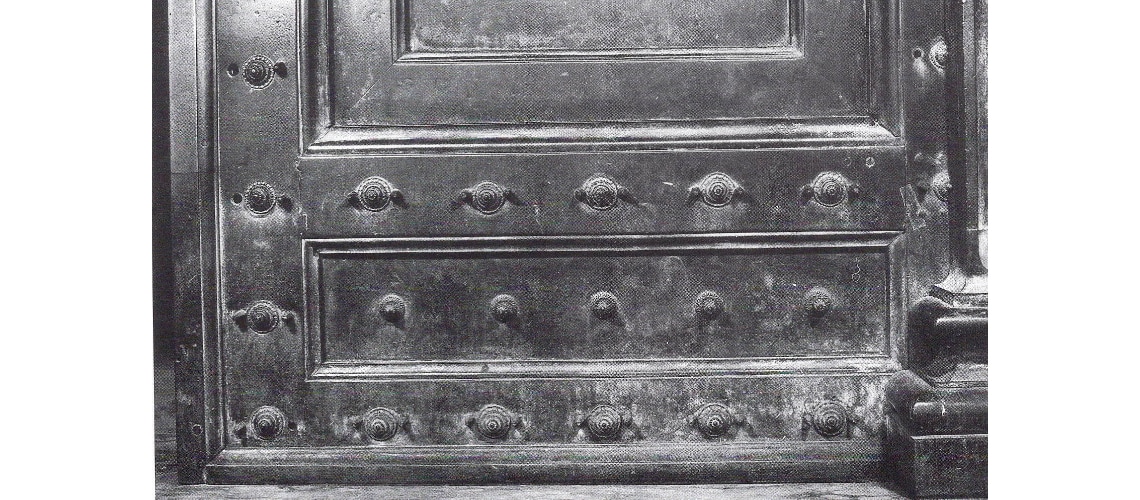

- The Holy Door

- Il Porcellino

- Las Vegas

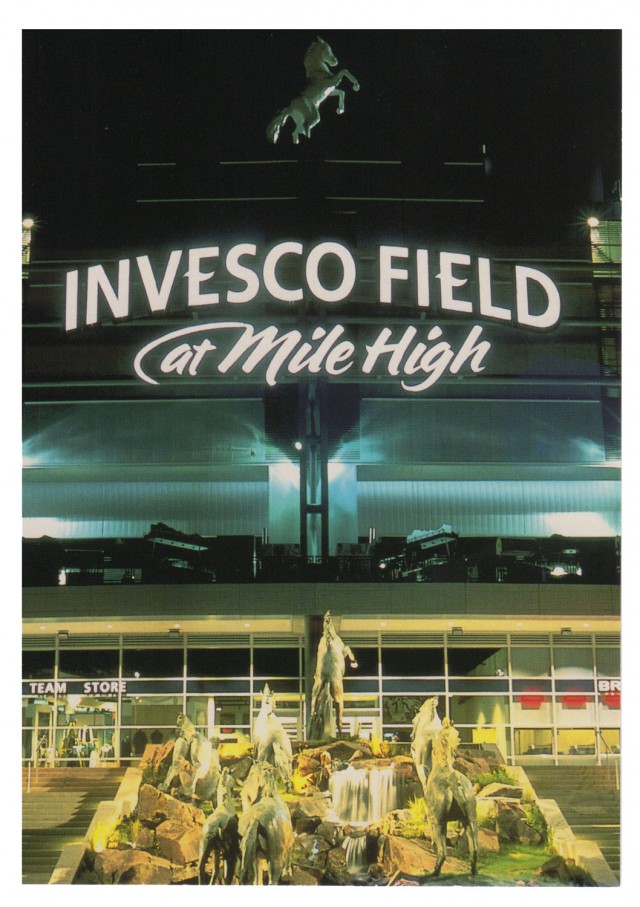

- The Broncos Fountain

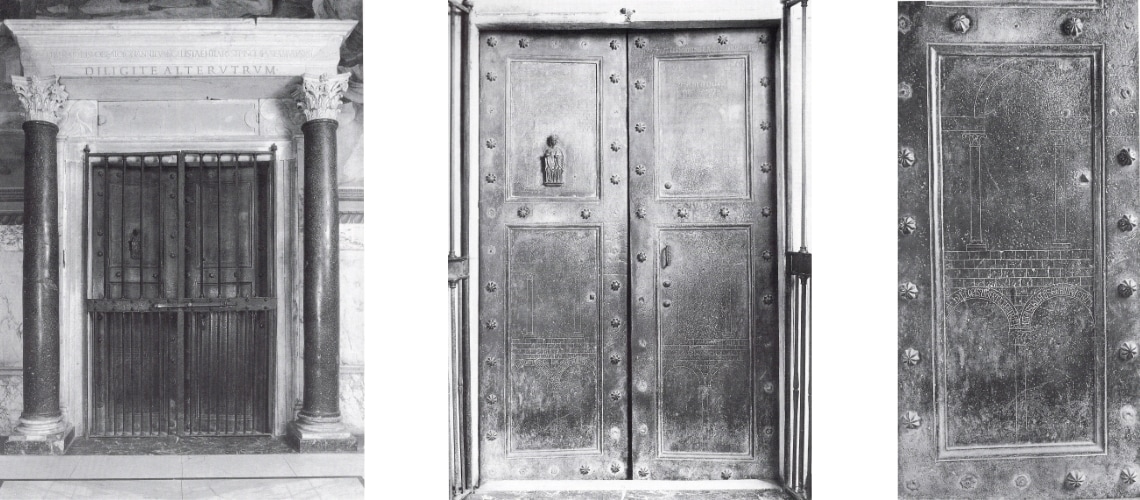

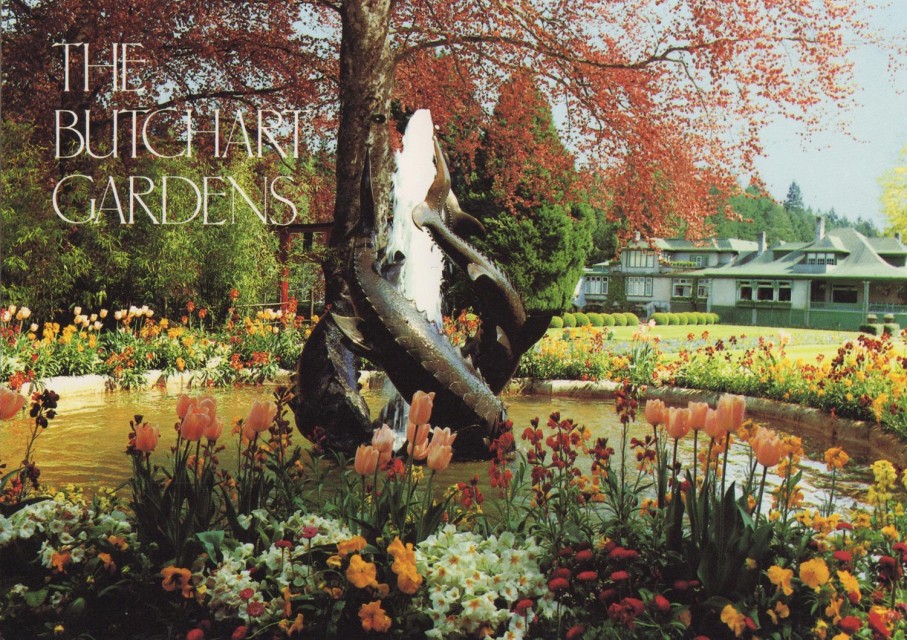

- Butchart Gardens

- Tritons' Fountain - Malta

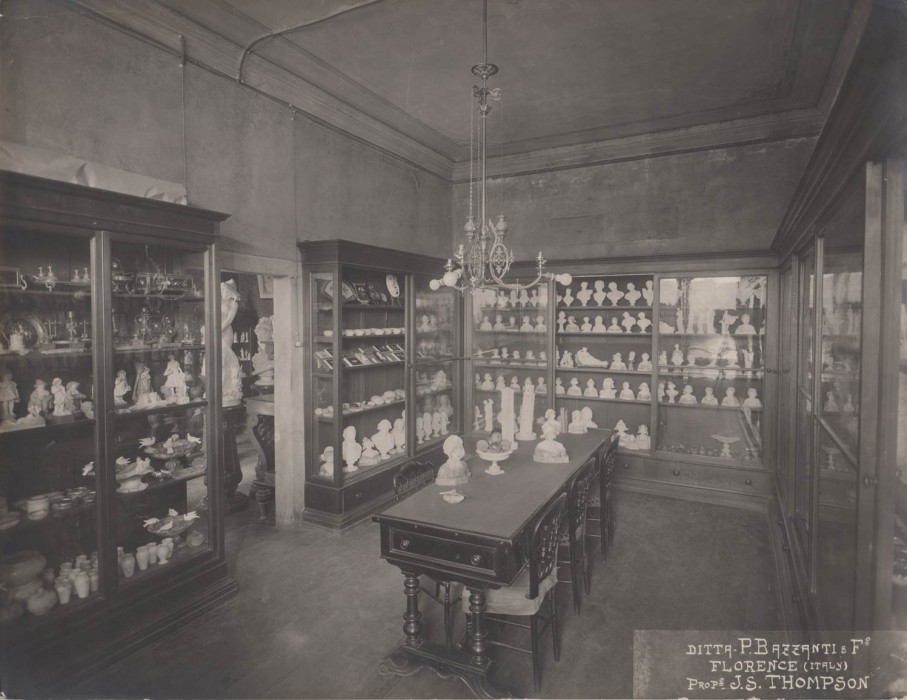

Bazzanti Gallery and Lungarno Corsini on vintage postcards:

1869 – The sculpture studio of Bazzanti Brothers at Palazzo Corsini, before the transformation into an art Gallery

1875 – The Bazzanti Gallery with its four shop windows in front of the Lungarno. The first three awnings are united, it’s possible to distinguish the Bazzanti inscription on the side.

.

1890 – The awnings are painted with a large inscription ‘Pietro Bazzanti e F.’

.

1903 – A squad of soldiers pass nearby the Gallery.

.

Early ‘900 – The white awnings have been simplified.

.

Early ‘900 – On the far left, the Gallery’s awnings.

.

Undated – The Gallery’s awning is the only one of the Lungarno Corsini.

.

1928 – The four awnings are now separated.

.

Undated – The windows of the gallery are clearly visible, with some marble sculptures inside. The stamp in violet is coeval.

.

Flood of 1966 – Some days after the water subsided

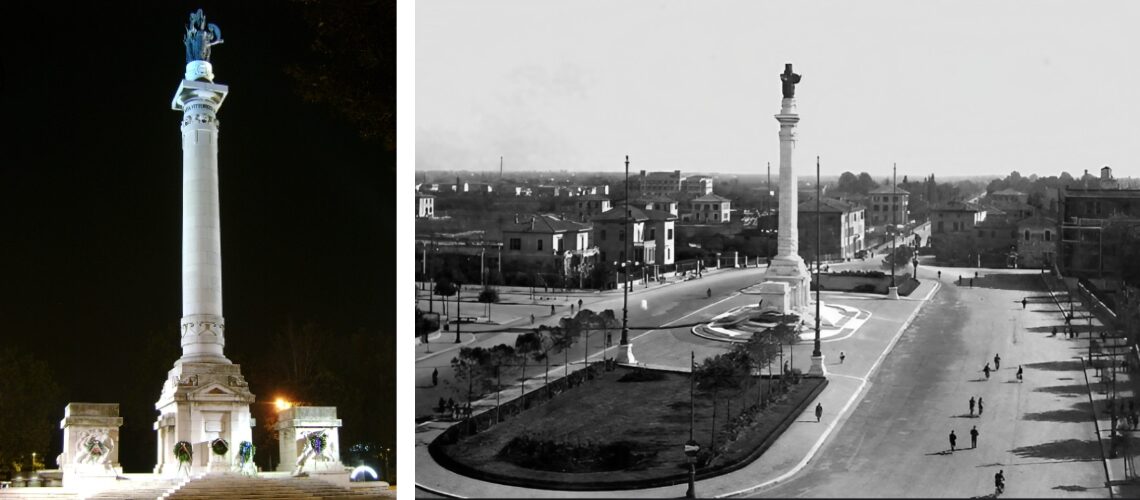

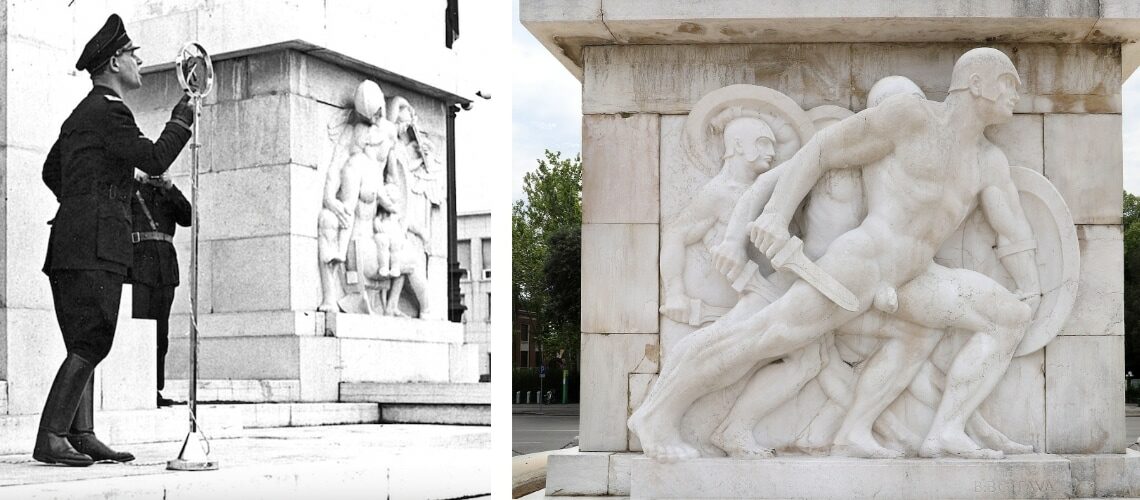

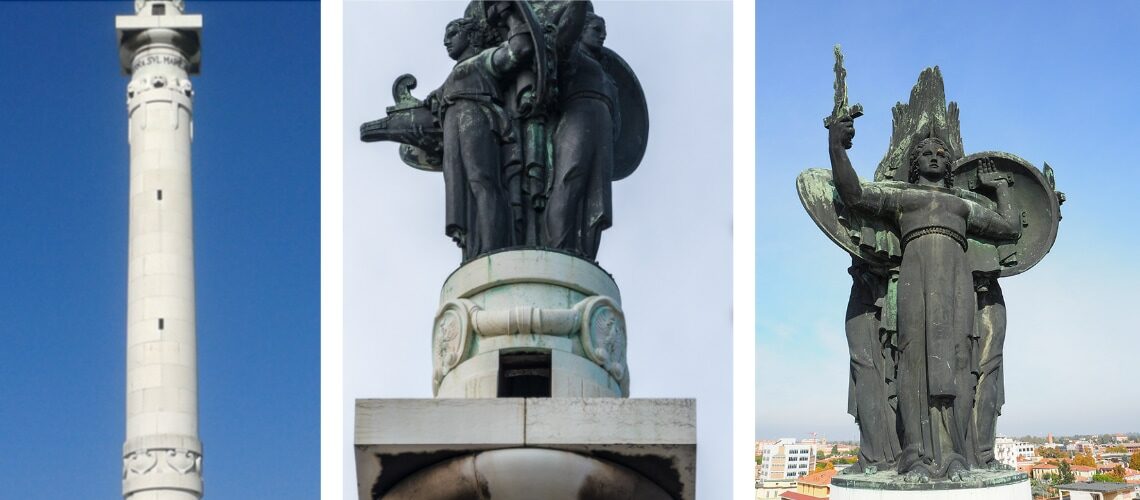

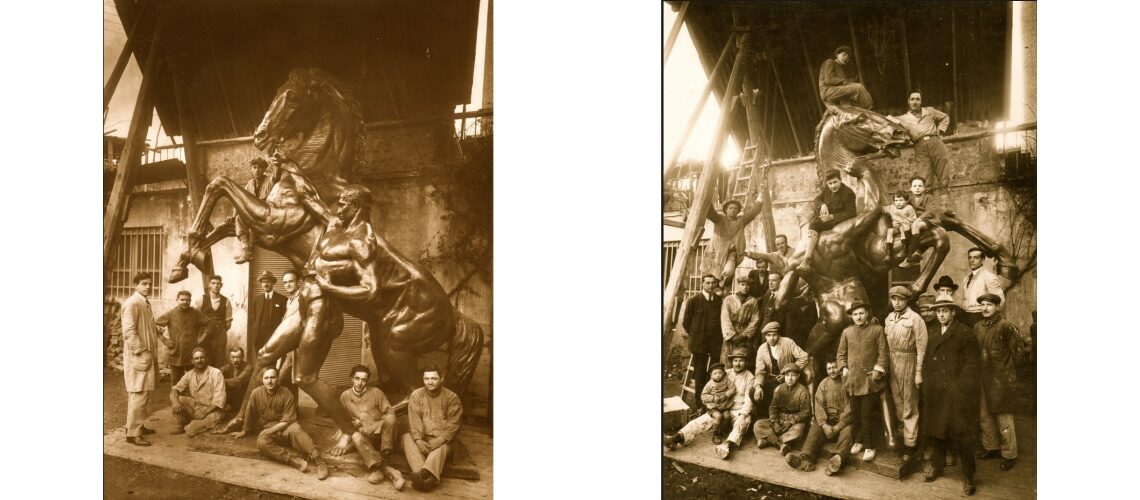

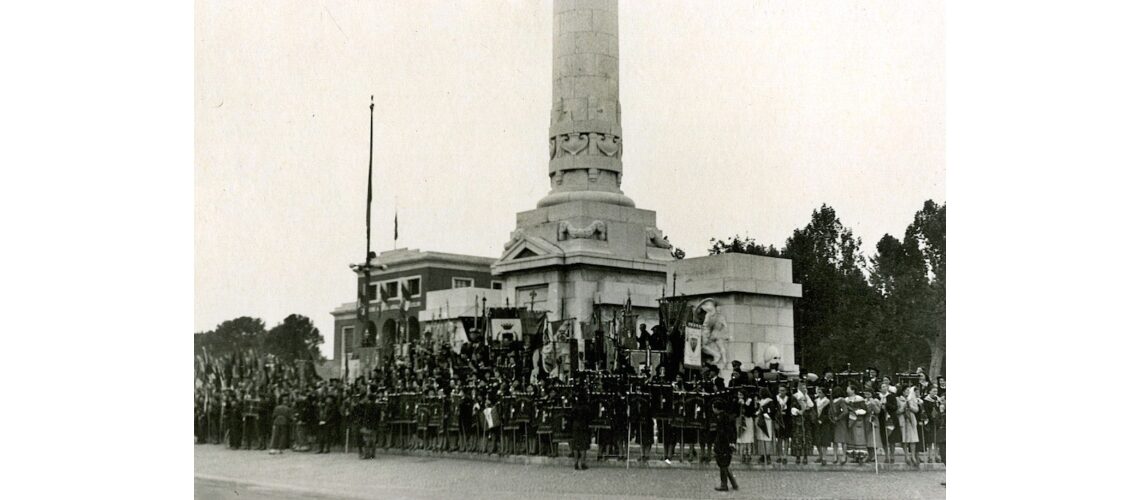

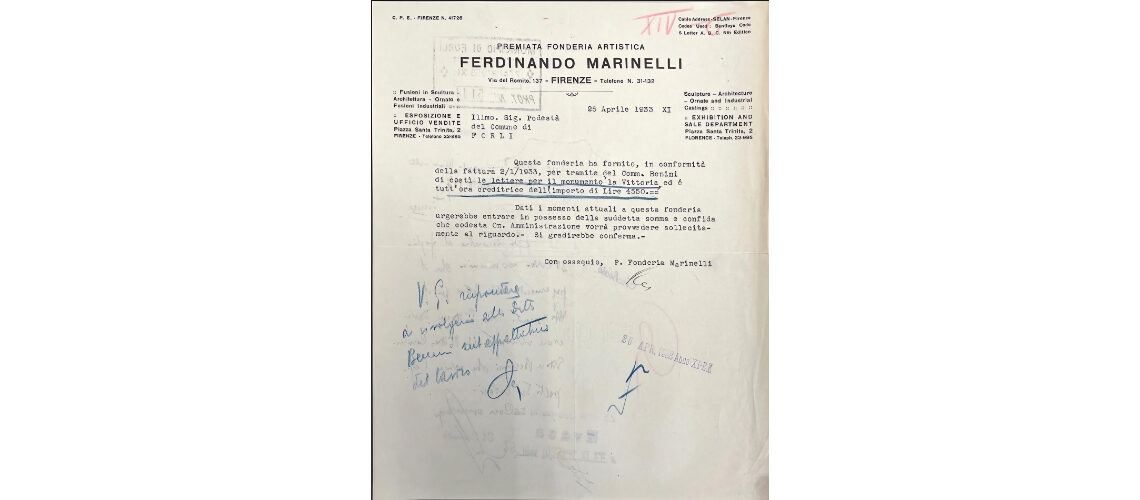

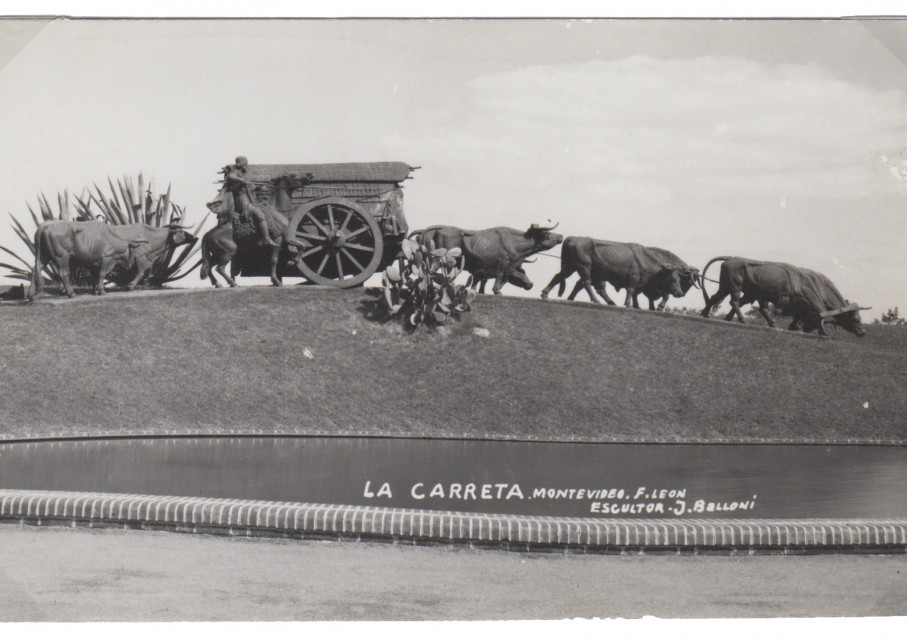

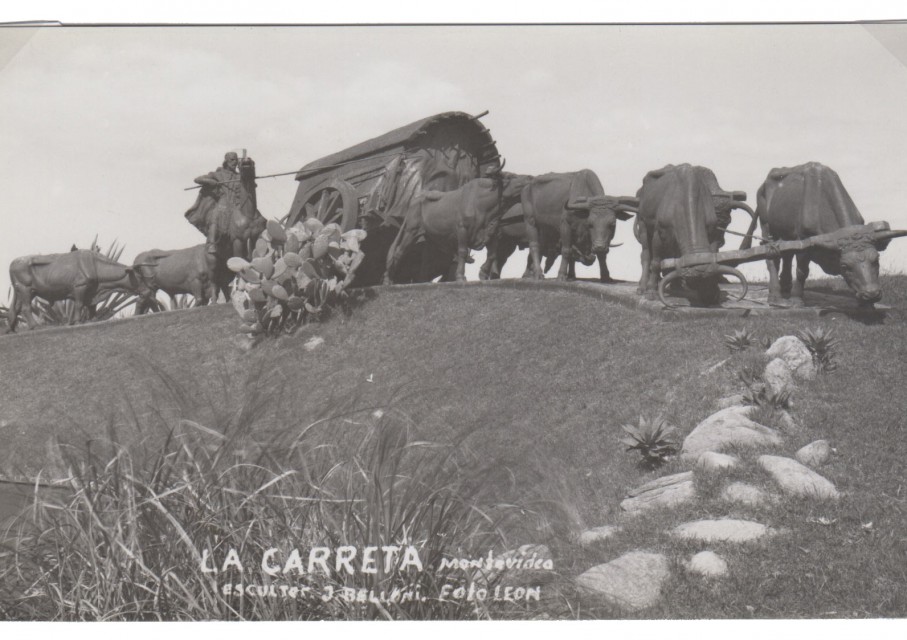

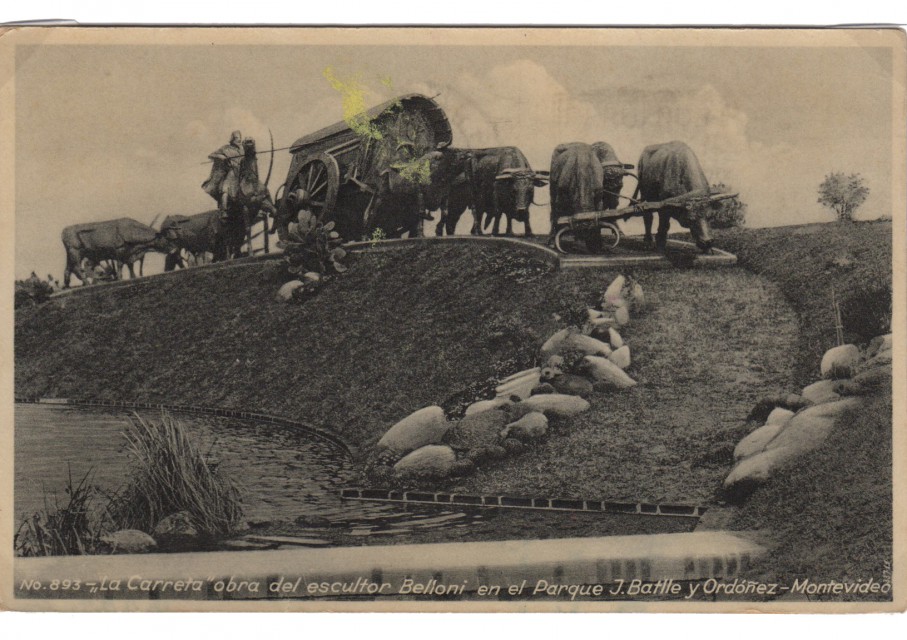

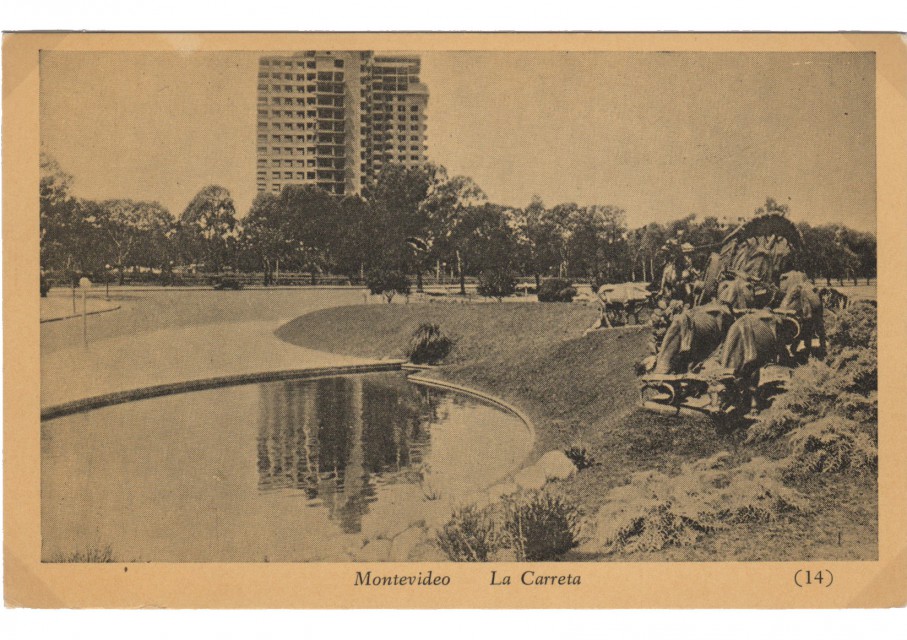

The postcards are from photographs taken shortly after the installation of the monument of Jose Belloni in Montevideo (Uruguay) in 1930, melted by the Ferdinando Marinelli Artistic Foundry in Florence.

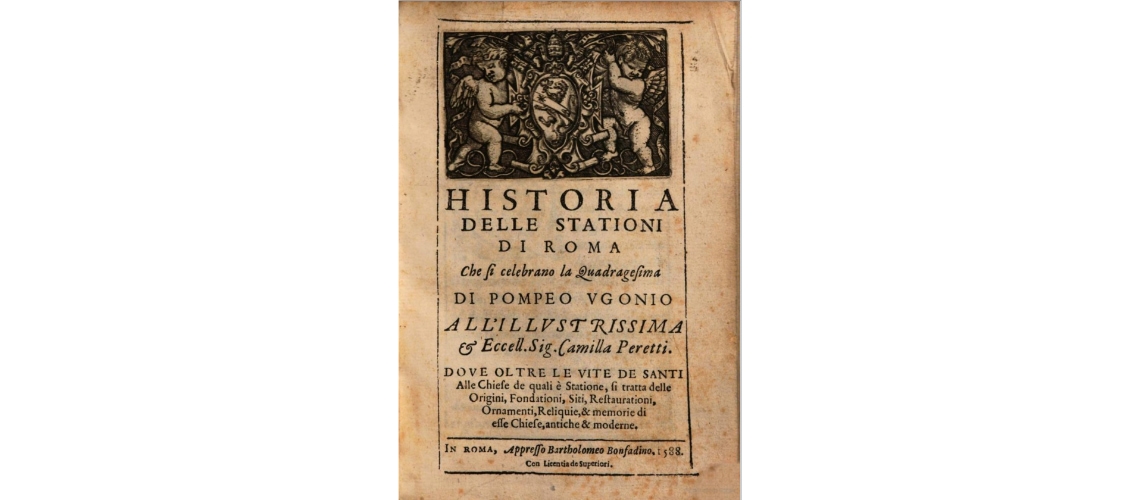

Le cartoline postali hanno l’immagine dello scalone monumentale fuso e montato nel 1932 dalla Fonderia Artistica Ferdinando Marinelli di Firenze all’ingresso del Museo Vaticano, poco prima dell’inaugurazione.

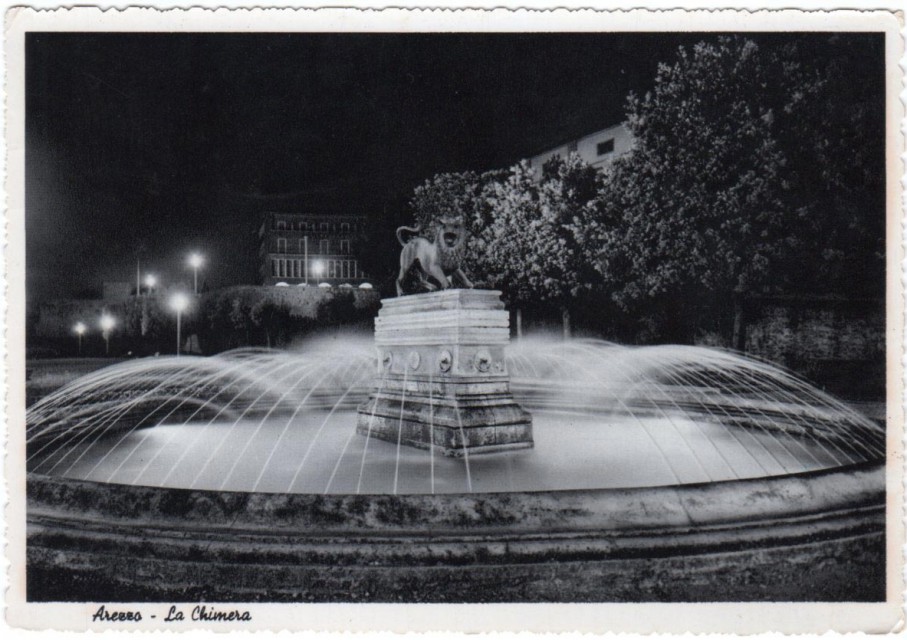

Postcards of the two bronze Chimeras of Piazza della Stazione in Arezzo, cast by Fonderia Artistica Ferdinando Marinelli of Florence.

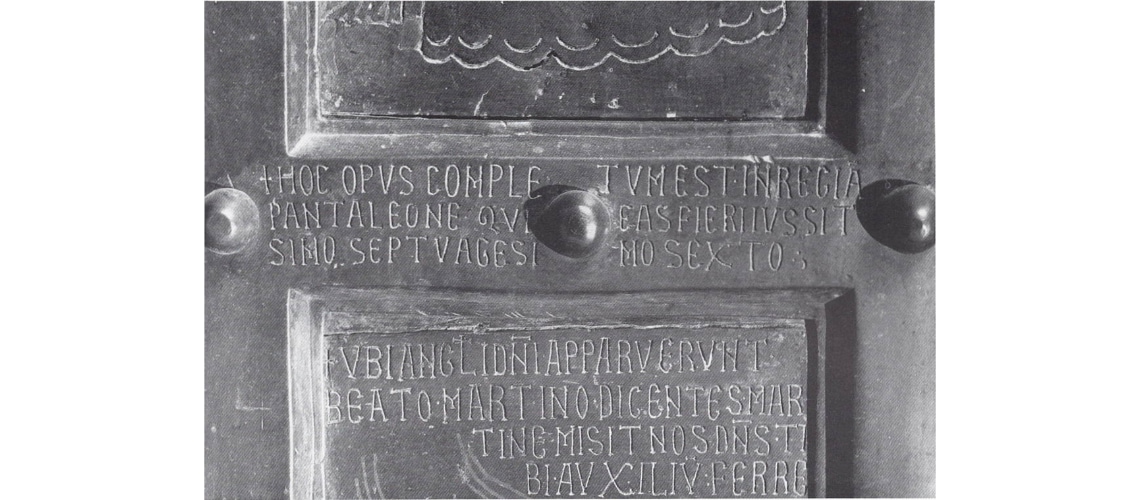

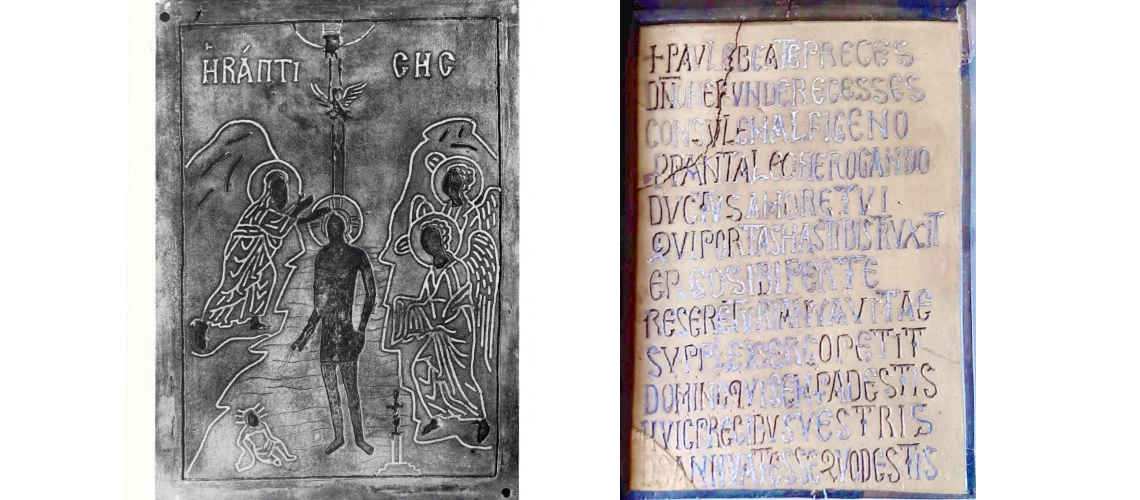

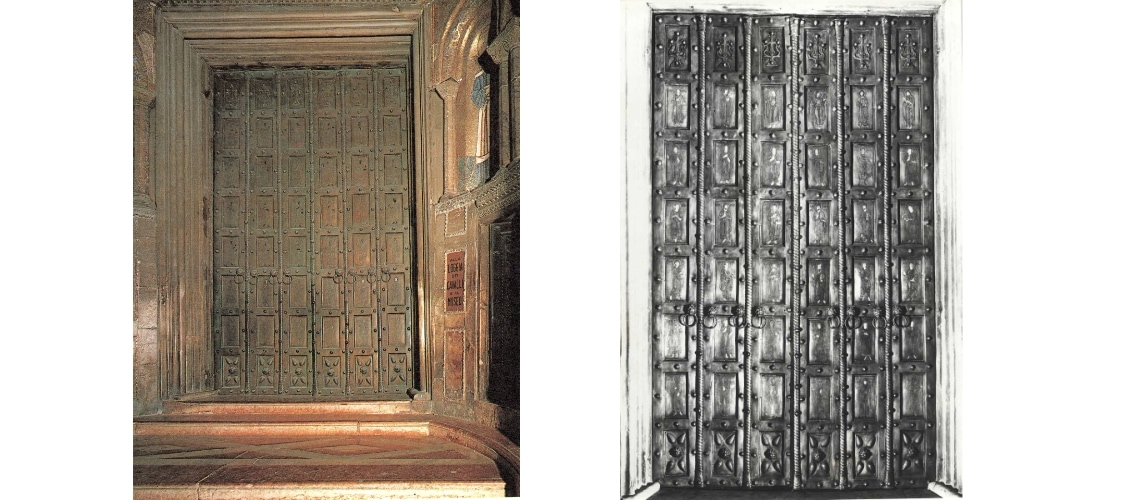

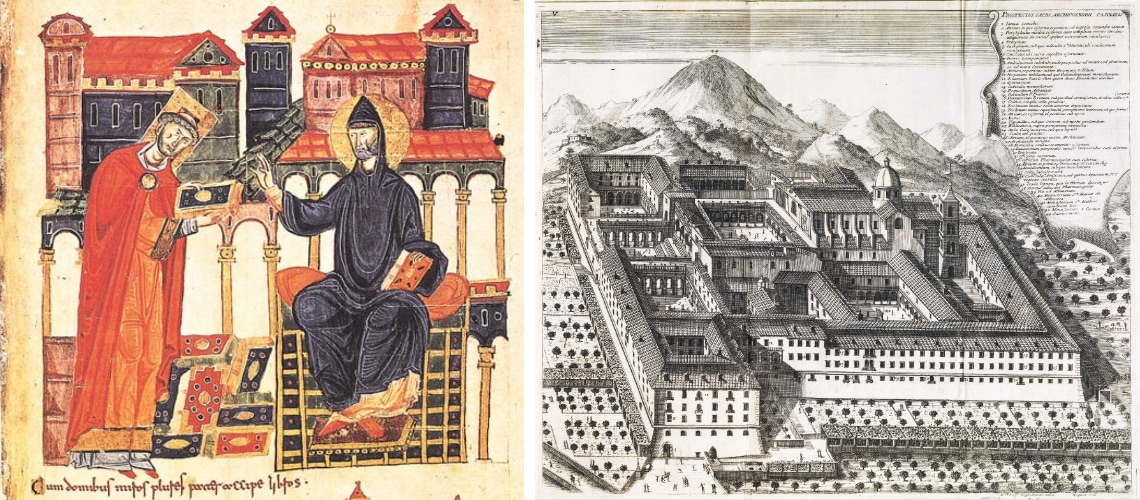

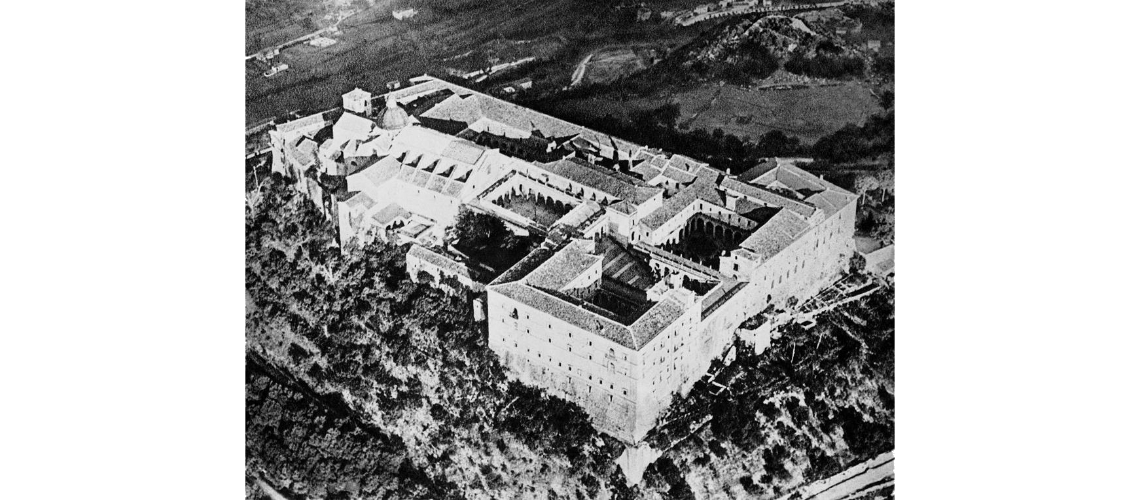

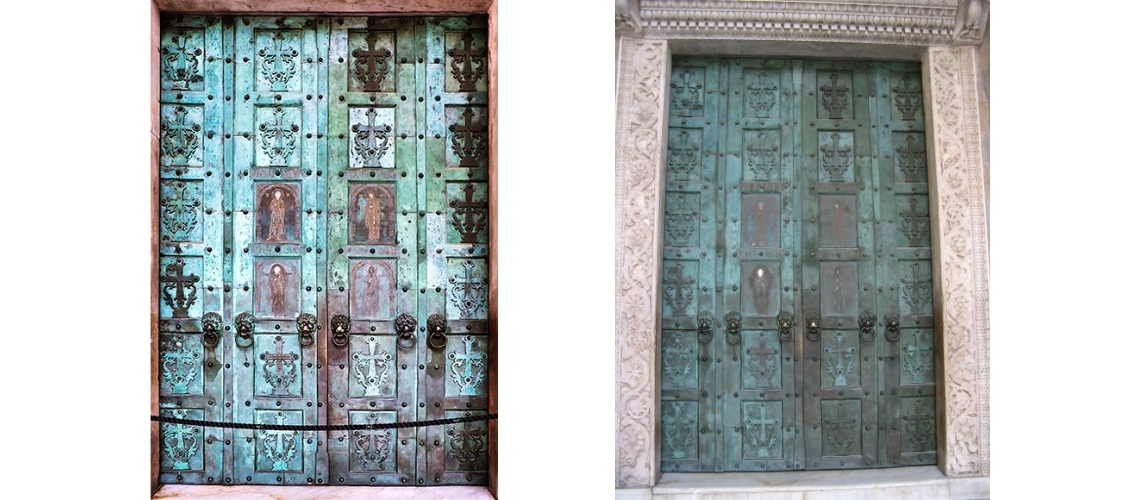

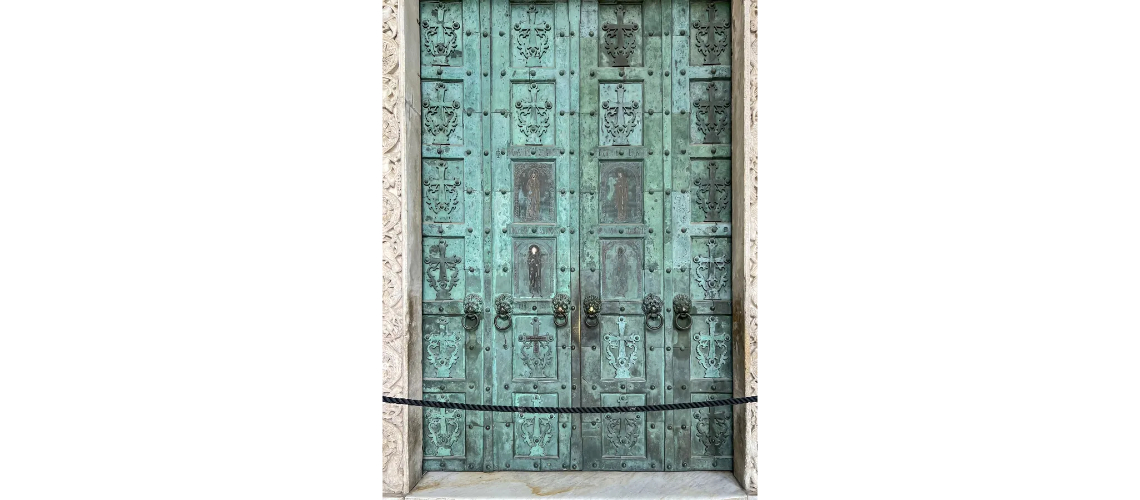

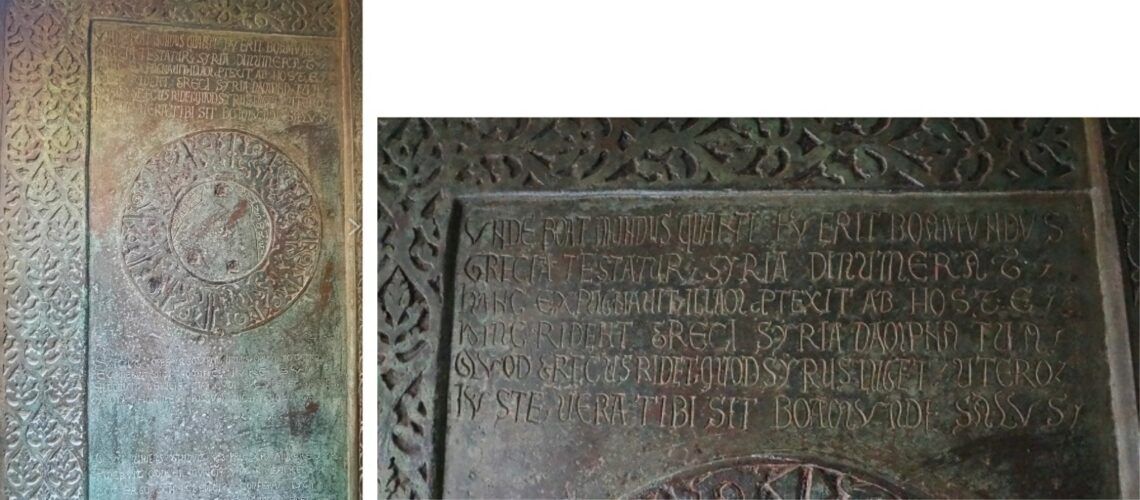

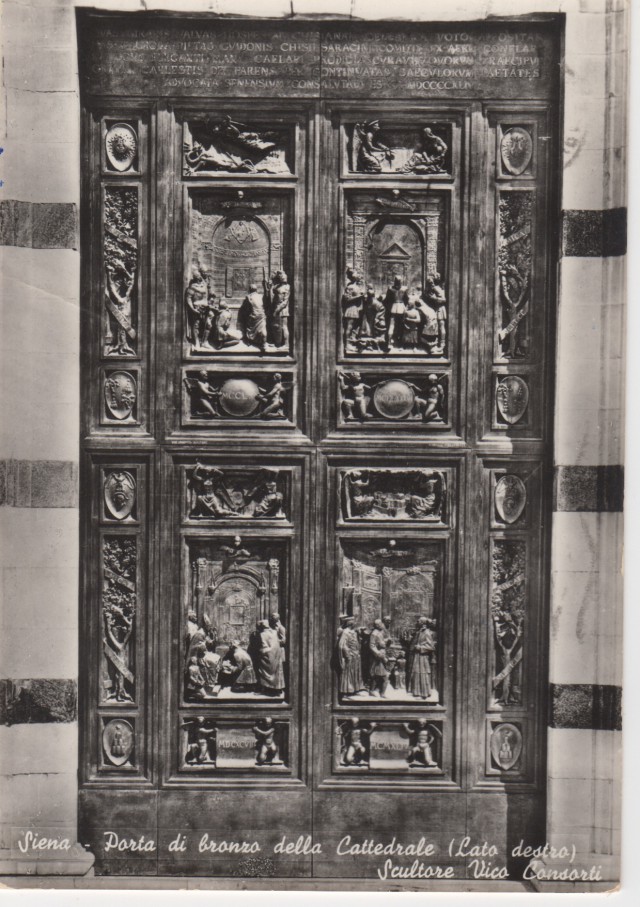

As a sign of gratitude for the liberation of the city from the Germans, Count Chigi Saracini of Siena asked the Sienese sculptor Vico Consorti to create the so-called Gate of Gratitude for the Duomo of Siena. It was cast by the Fonderia Marinelli.

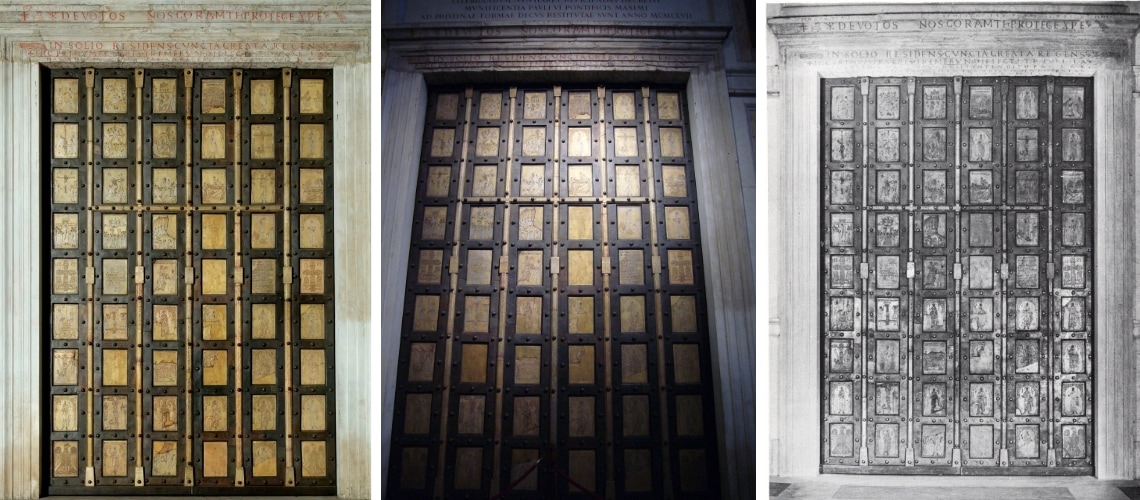

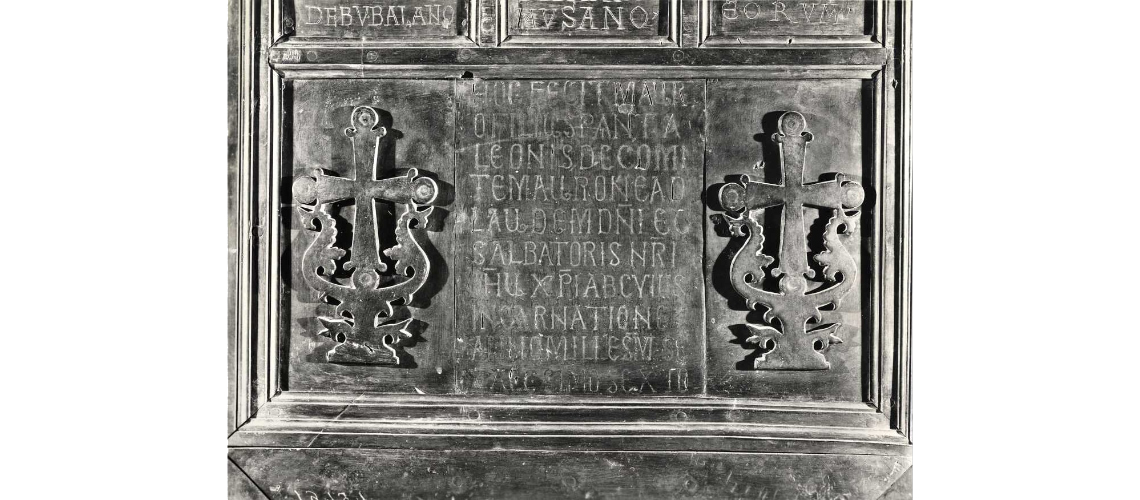

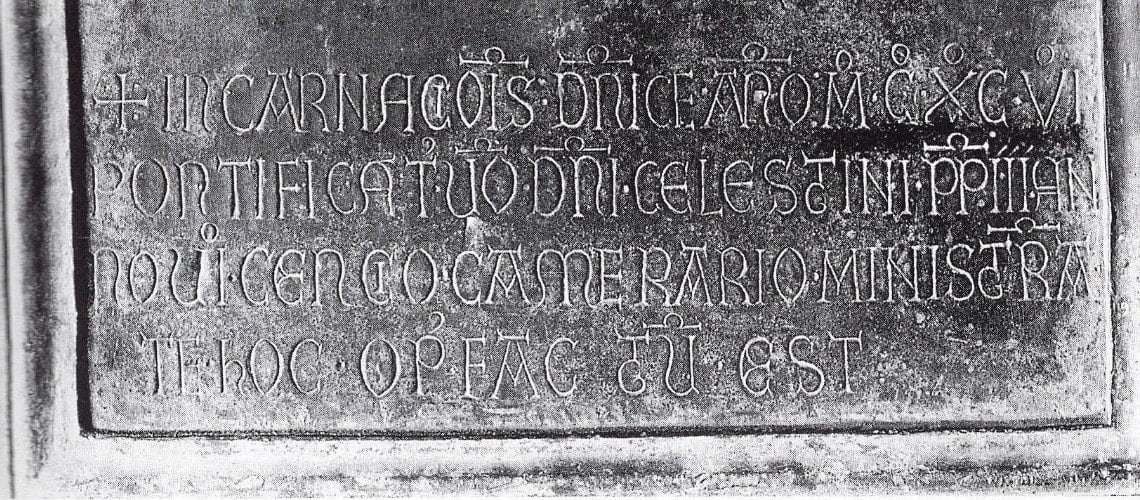

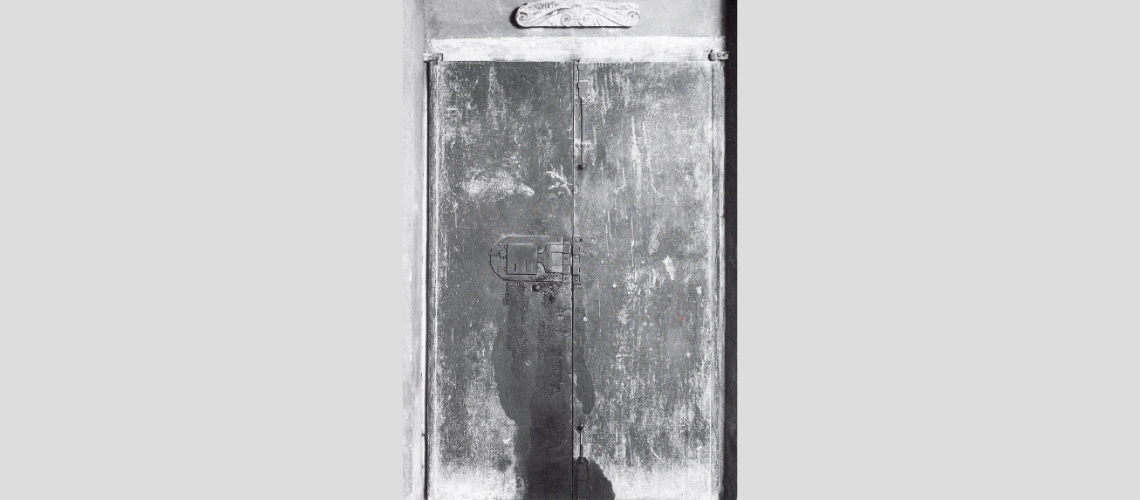

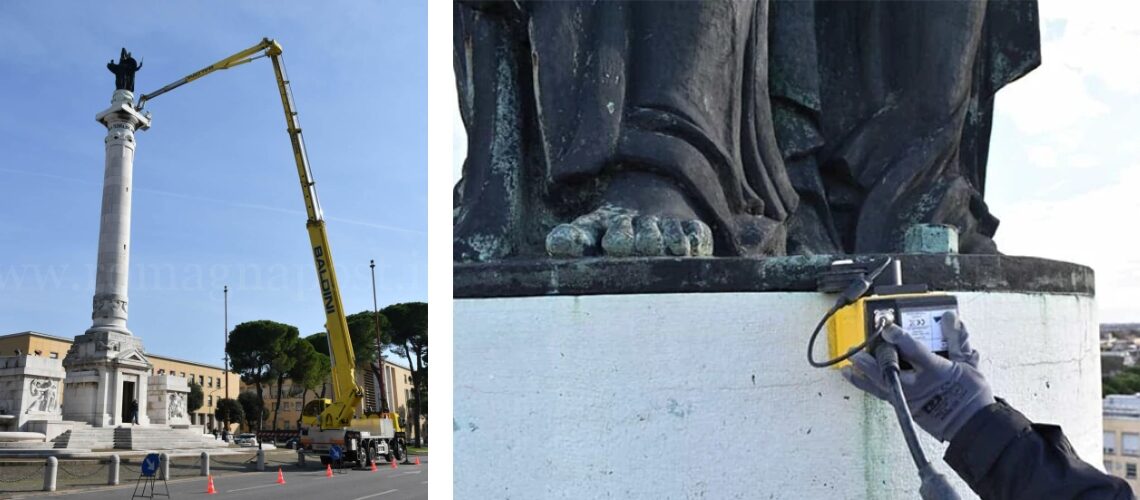

La cartolina postale è stata stampata per la Porta Santa della Cattedrale di San Pietro in Vaticano fusa in bronzo dalla Fonderia Artistica Ferdinando Marinelli di Firenze nel 1950. Ha sostituito la precedente in legno. Viene aperta dal Papa solo in occasione dei Giubilei.

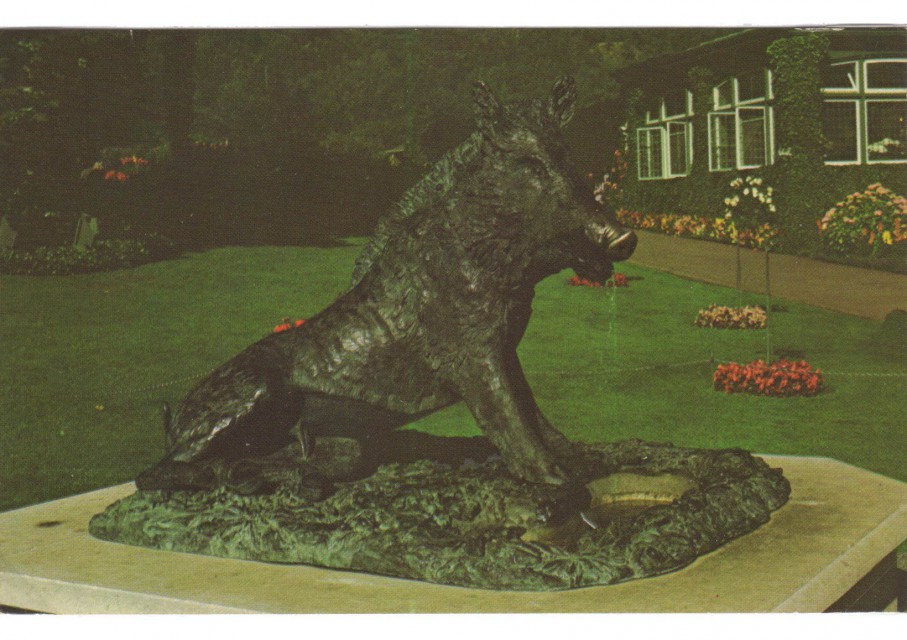

Replica della celebre fontana fiorentina del Porcellino del Tacca che la Galleria Bazzanti ha inviato nella città di Victoria, Canada, per ornare il Butchart Garden, di cui ne hanno fatto una cartolina.

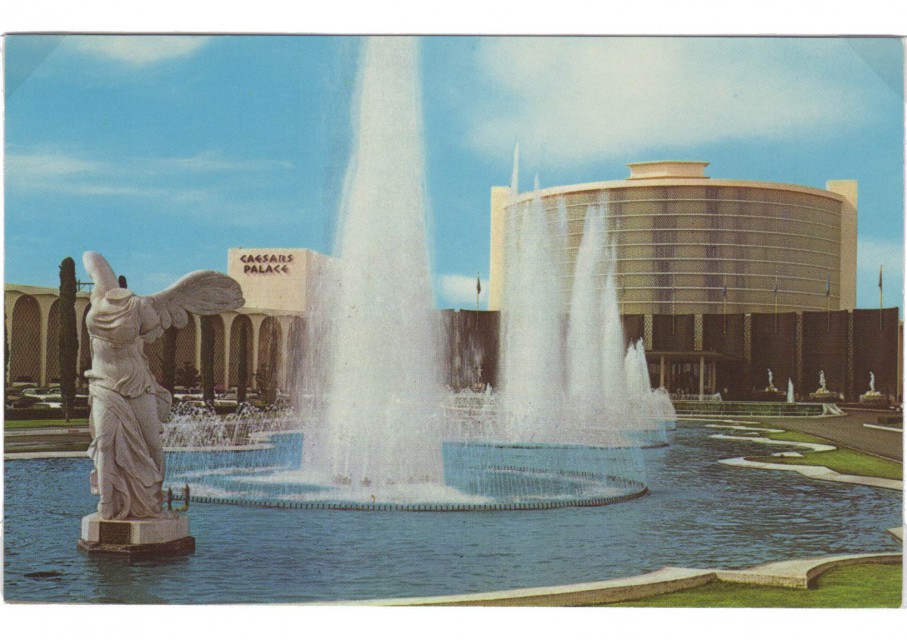

Cartoline del Caesar Palace Hotel di Las Vegas a cui la Galleria Bazzanti ha fornito gran parte delle statue di marmo di Carrara degli arredi esterni ed interni.

Testo da definire

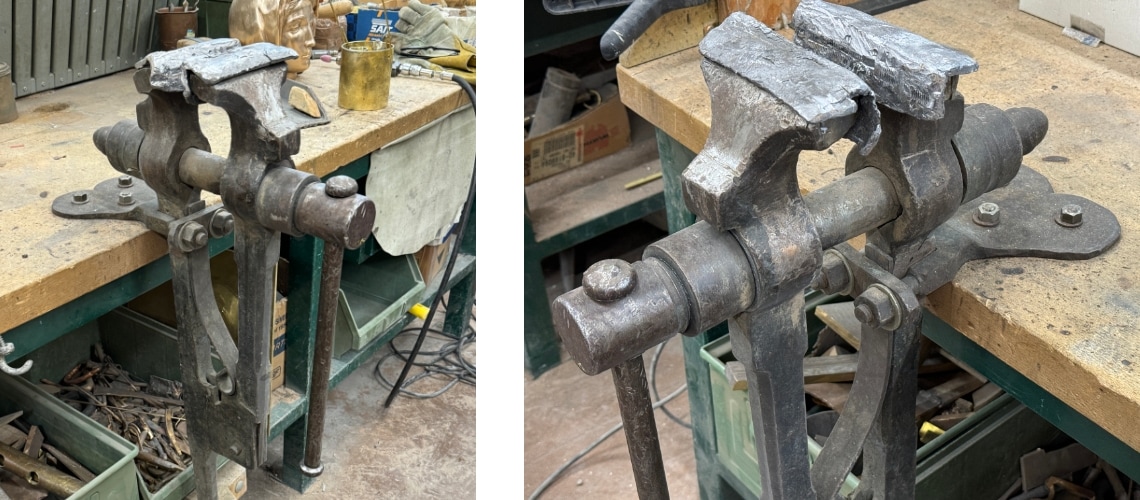

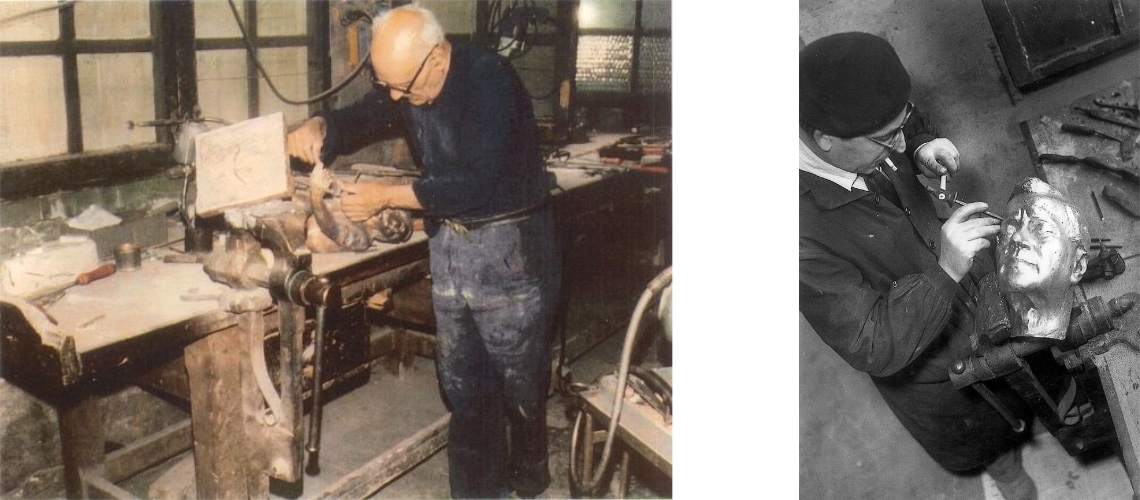

60’s

1969