The Bernini's David

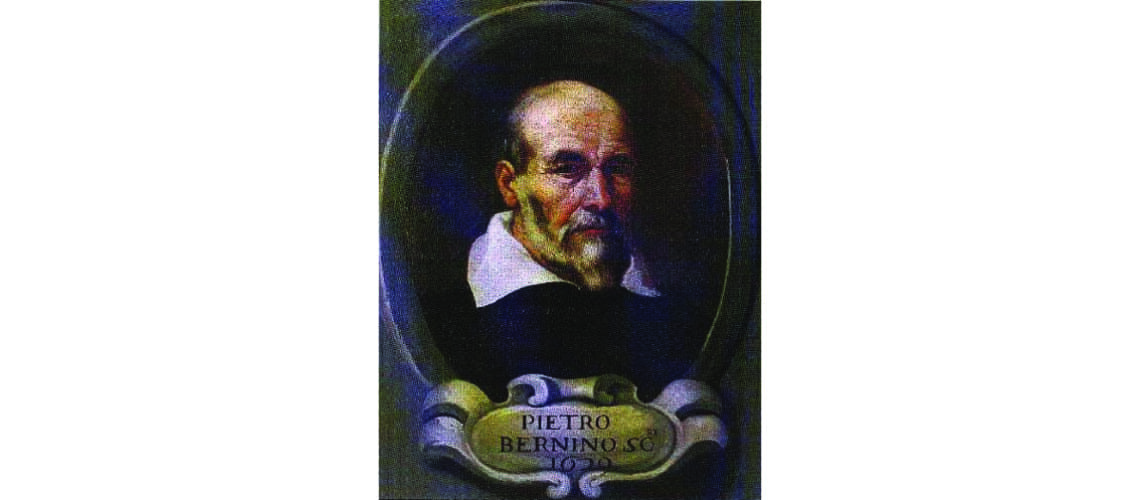

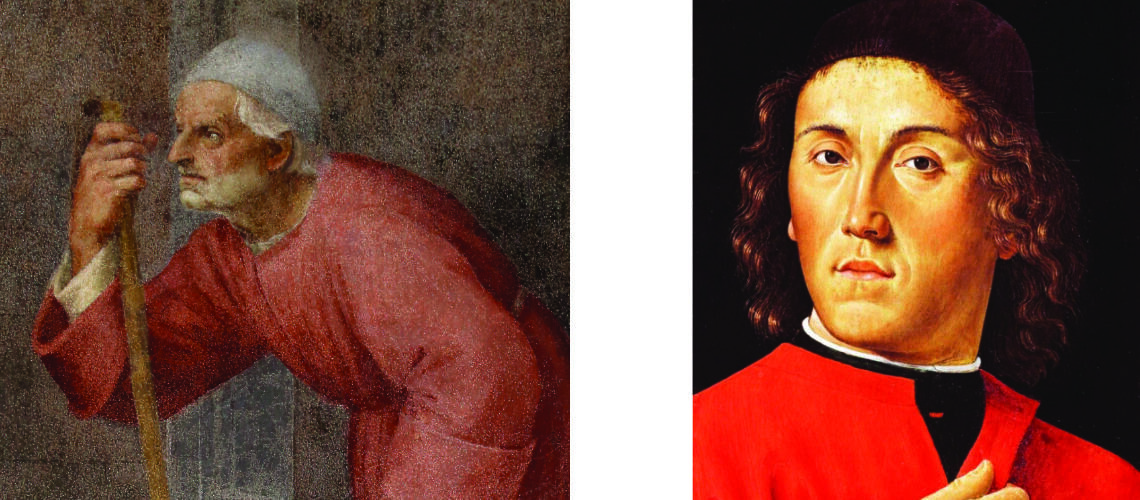

Pietro Bernini was born in Sesto Fiorentino in 1562.

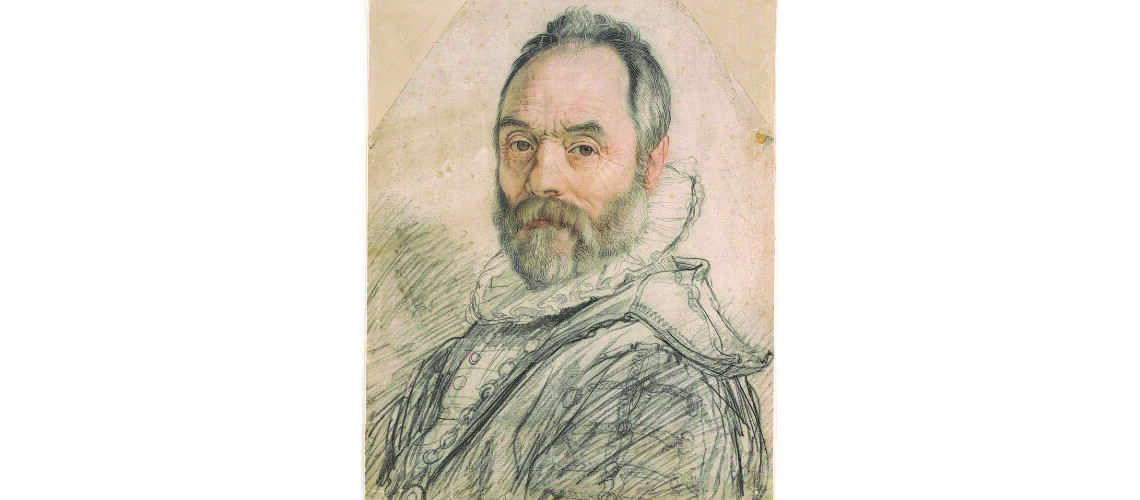

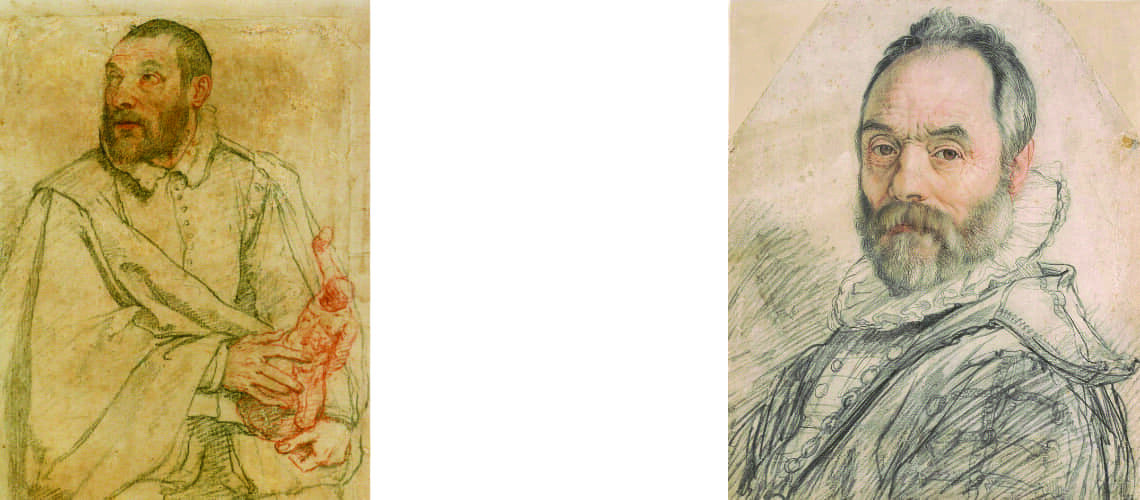

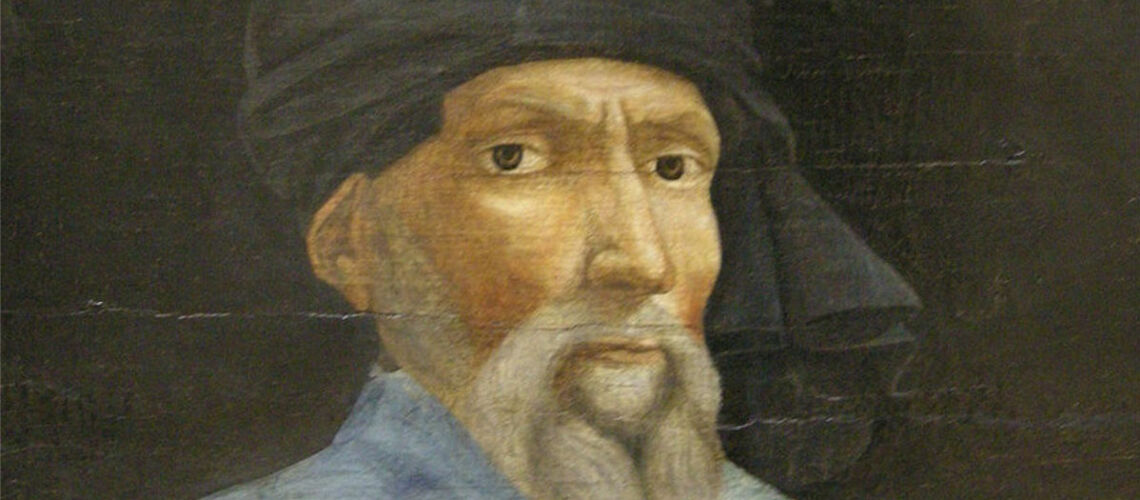

Pietro Bernini

He learned to sculpt in the workshop of the Florentine Ridolfo Sirigatti, and to paint in the one in Rome of the Cavalier d’Arpino, a well-known mannerist.

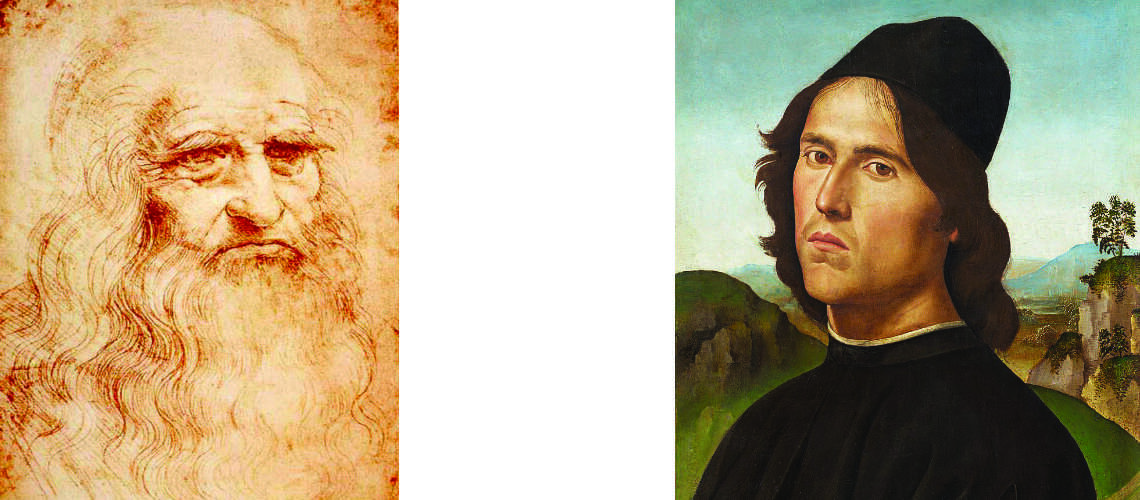

Cavalier d’Arpino, self portrait, 1640

In 1596 he was called by the viceroy of Naples to sculpt figures for the Certosa di San Martino. And it was in Naples that in 1598 his wife Angelica Galante gave birth to Gian Lorenzo.

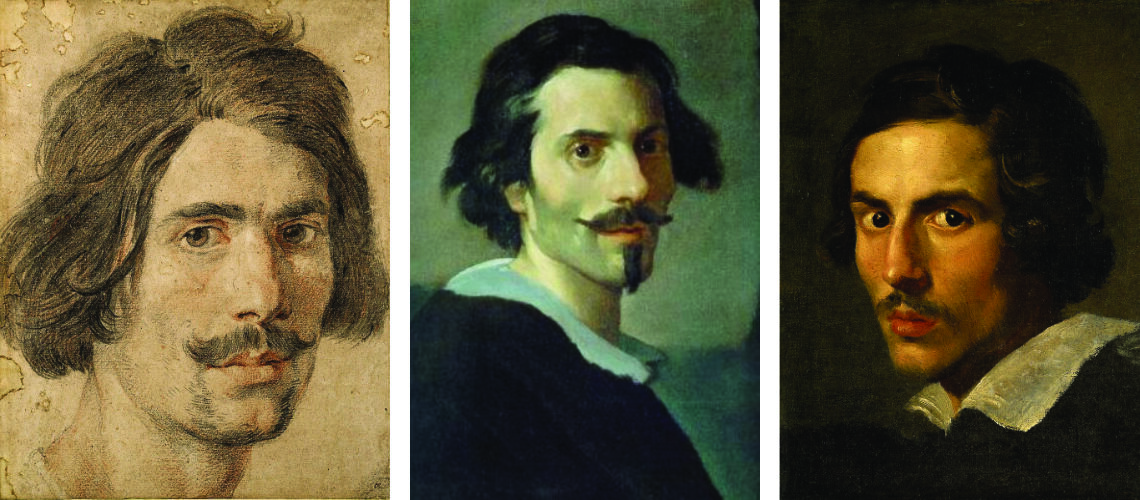

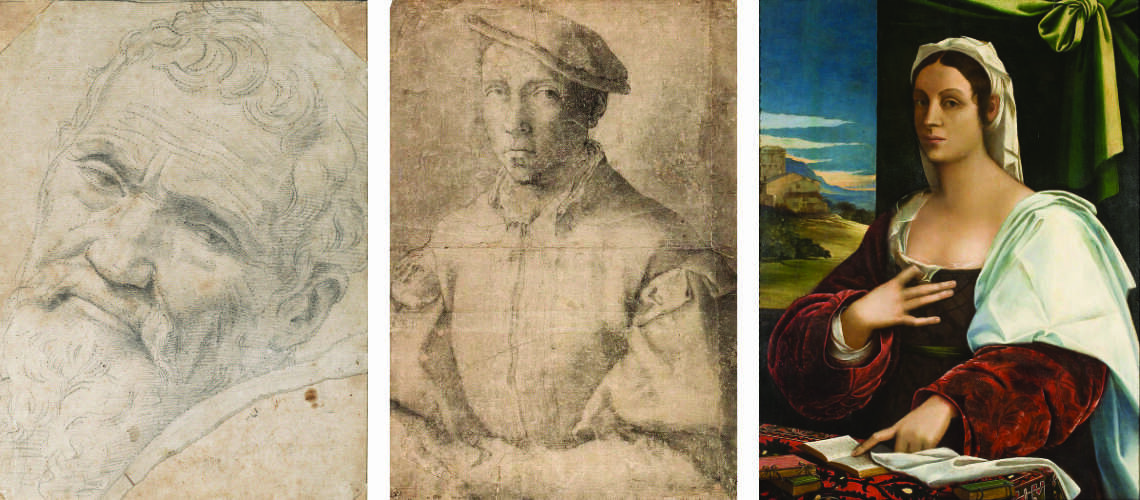

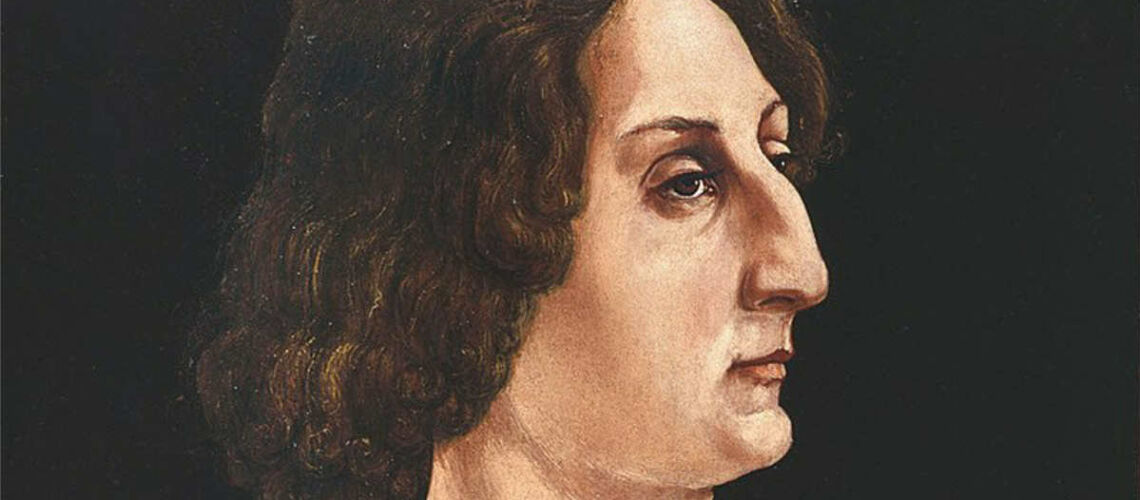

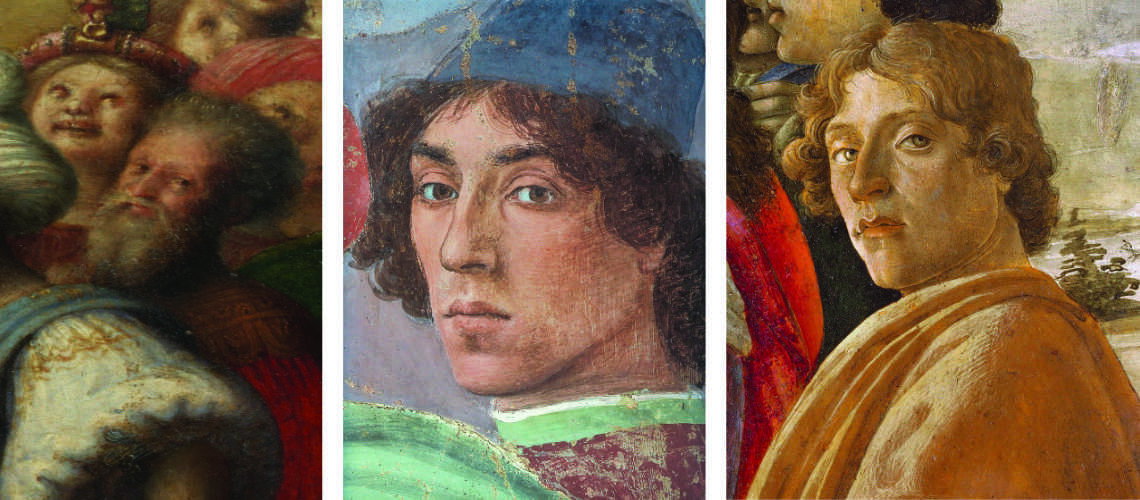

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, self portrait Uffizi | Gian Lorenzo Bernini, self portrait, 1625, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford | Gian Lorenzo Bernini, self portrait, Galleria Borghese |

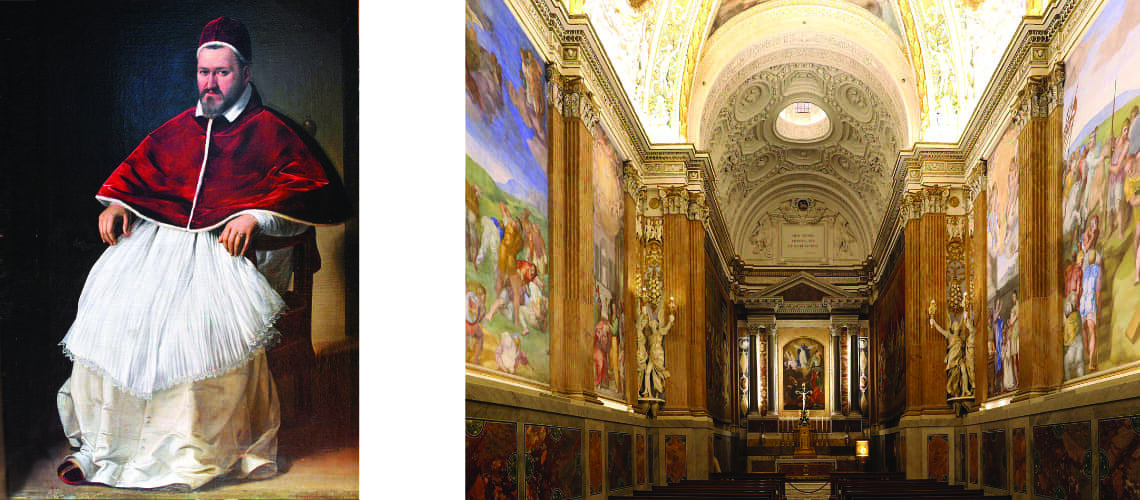

But in 1606 Pietro was called by Pope Paul V to work on the construction site of the Pauline Chapel in Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, where he moved with his wife and son Gian Lorenzo, who already at a young age was acting as his father’s shop boy.

| Papa Paolo V Borghese, Caravaggio, 1606, Palazzo Borghese | Cappella Paolina, Santa Maria Maggiore a Roma |

Gian Lorenzo e Pietro in Rome

In those first decades of the 17th century, Rome was a point of reference in painting and sculpture for the nascent Baroque art, an art in which Caravaggio had opened a new narrative and figurative style by creating lively and realistic characters inspired by the common people, playing in an exceptional and new with light and darkness.

Caravaggio, Judith and Holofernes, 1602, National Gallery of Ancient Art, Palazzo Barberini

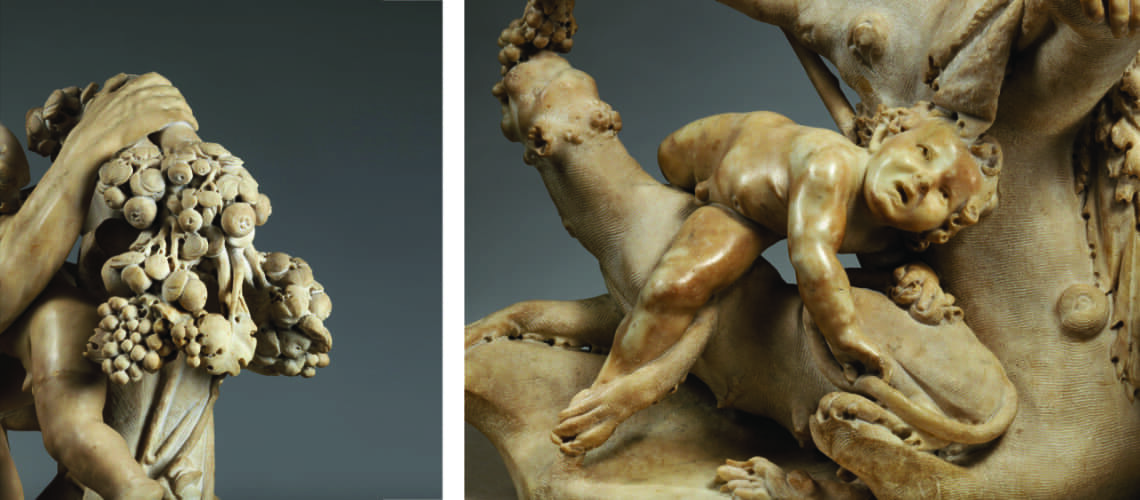

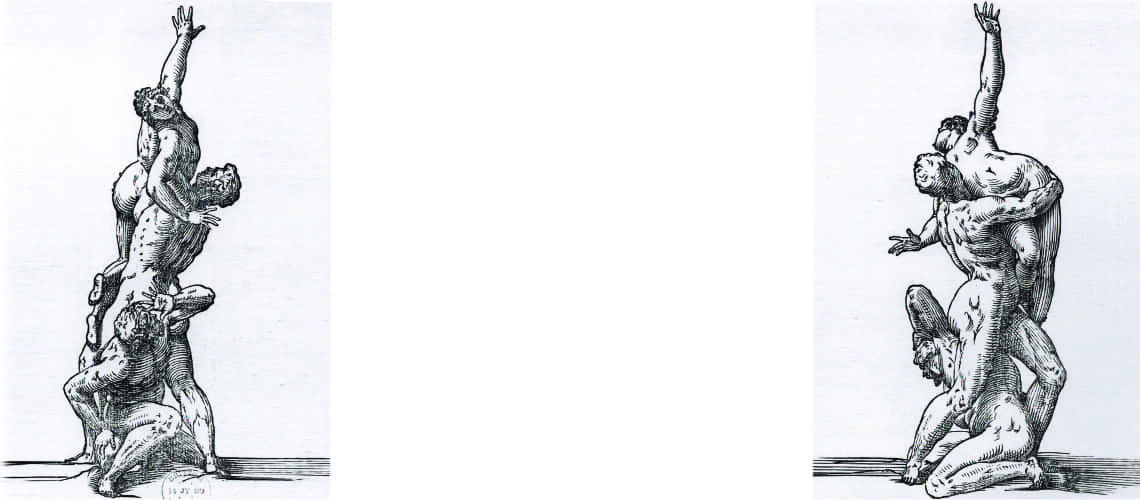

But soon, already in 1609, Gian Lorenzo Bernini began working on the marbles that his father Pietro sculpted, which increasingly became works made by four hands, demonstrating an unlikely talent for his age; the group of the Faun with Cupids which remained in Gian Lorenzo’s house for many years after his death is famous. In this work the sixteenth-century mannerist imprint due to Pietro’s hand is still visible, as is the inspiration taken by looking at Michelangelo in the composition and softness of the shapes and surfaces, but with new poses and new movements of the bodies.

| Pietro and Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Faun with Cupids, Metropolitan Museum, New York | Pietro and Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Faun with Cupids, Metropolitan Museum, New York, detail |

| Pietro and Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Faun with Cupids, Metropolitan Museum, New York, detail | Pietro and Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Faun with Cupids, Metropolitan Museum, New York, detail |

His father Pietro introduced Gian Lorenzo Bernini to the Florentine cardinal Maffeo Barberini, Pope Urban VIII, for whom Gian Lorenzo executed some figures for the family chapel in Sant’Andrea della Valle in Rome between 1617 and 1618.

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, portrait of Pope Urban VIII, 1632, National Gallery of Ancient Art, Rome | Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Bust of Pope Urban VIII Barberini, bronze, 1658, Louvre |

Gian Lorenzo meets Cardinal Borghese

But it is with his cardinal nephew Scipione Borghese that Gian Lorenzo Bernini had the opportunity to express all his power and ability; not yet twenty years old he set about sculpting the large group of Aeneas, Anchises and Ascanius fleeing from Troy.

| Cardinal Scipione Borghese, Ottavio Leoni, Fesch Museum, Ajaccio | Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Aeneas, Anchises and Ascanius fleeing from Troy, 1619, Galleria Borghese | Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Aeneas, Anchises and Ascanius fleeing from Troy, detail, 1619, Galleria Borghese |

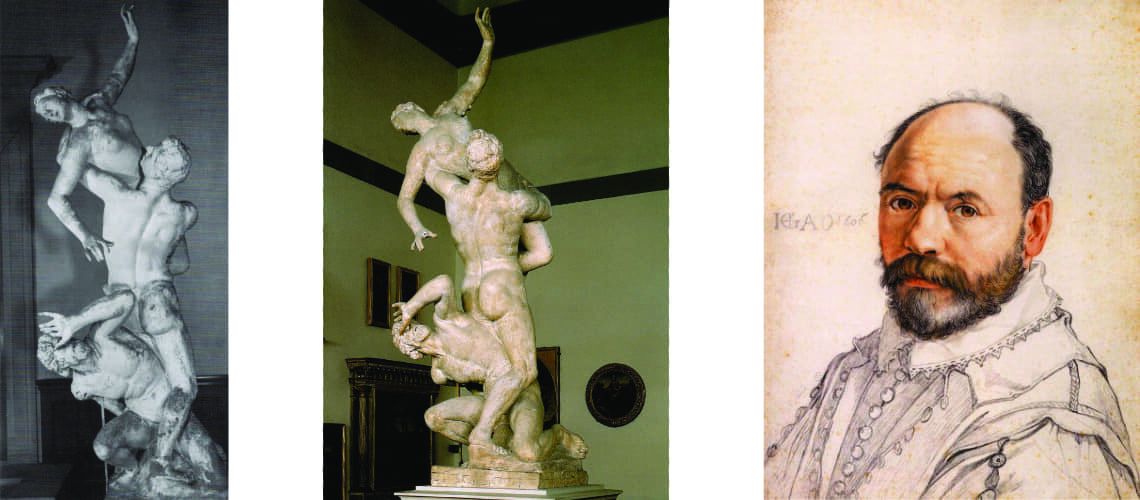

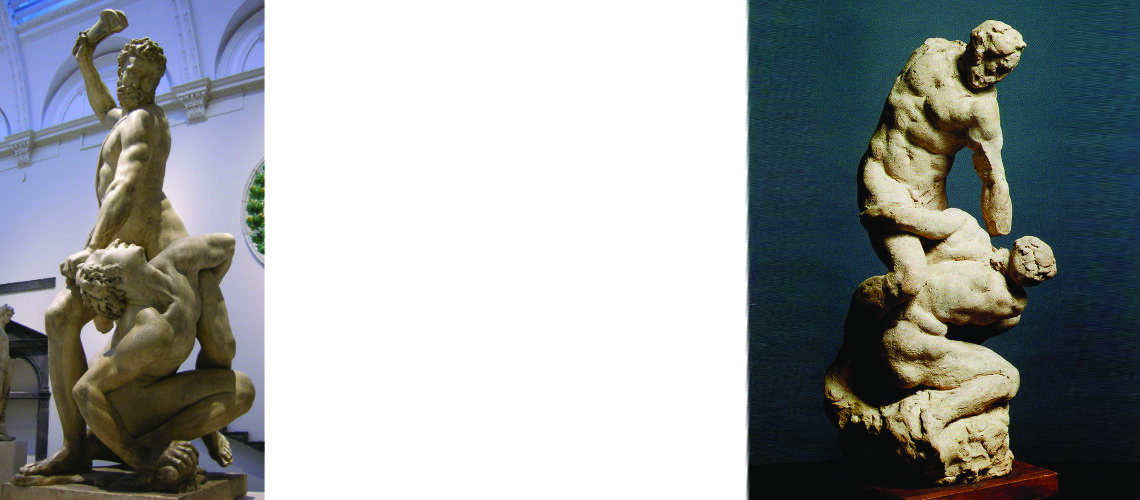

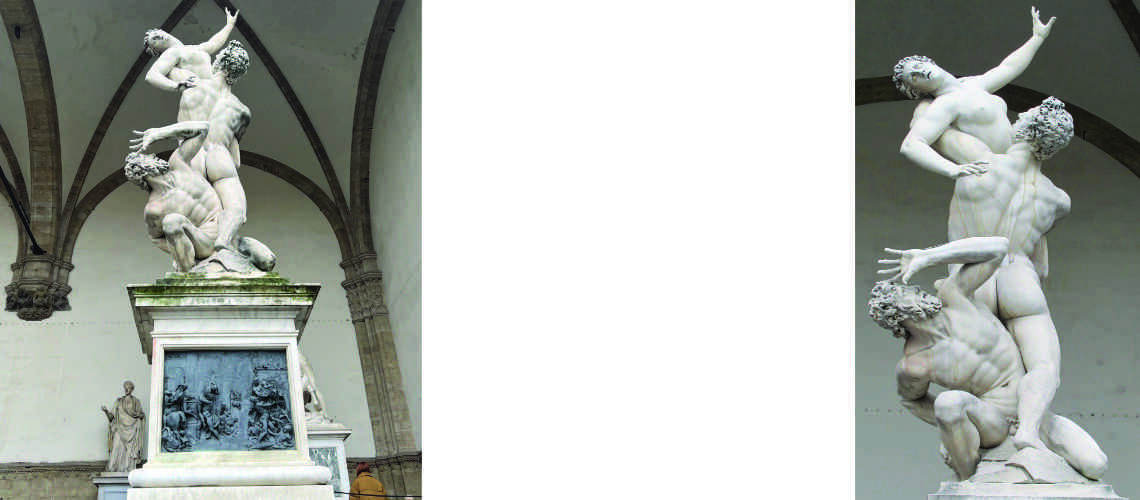

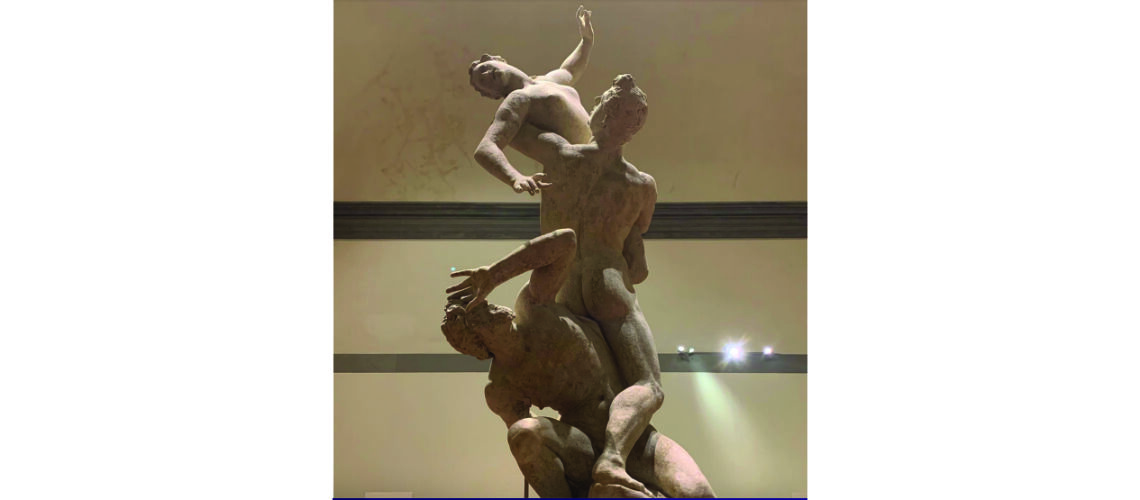

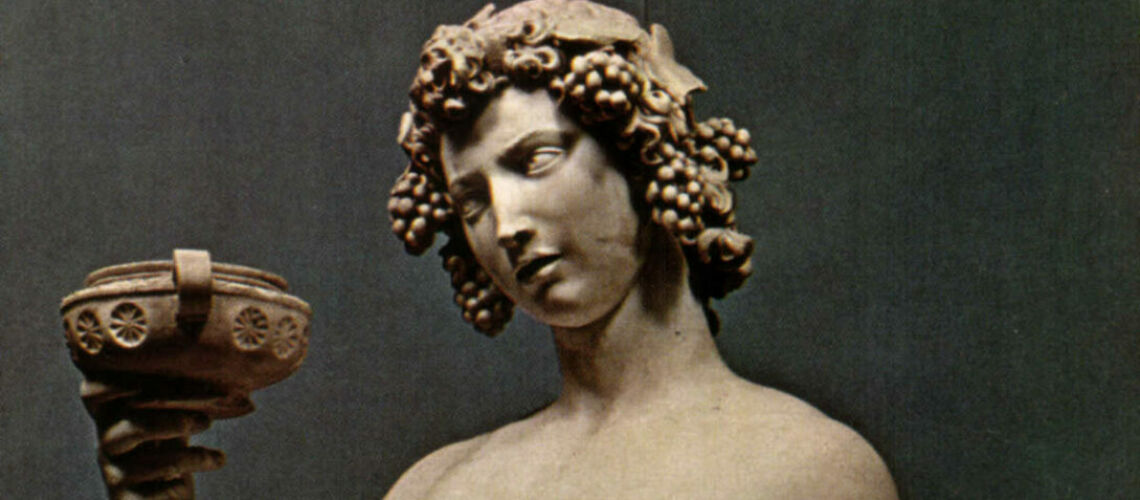

And in 1621, again for Cardinal Borghese, he performed the well-known group of the Rape of Proserpina, which the cardinal donated shortly afterwards to Ludovico Ludovisi, nephew of the new Pope Gregory XV. With this group Bernini highlights his great skill in sculpting groups of figures in movement and in complex poses.

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Rape of Proserpina, 1622, Galleria Borghese, Rome | Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Rape of Proserpina, 1622, Galleria Borghese, Rome (detail) |

| Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi, Ottavio Leoni, 1621, Budapest | Pope Gregory XV, Guercino, 1622, Getty Center, Los Angeles |

Cardinal Montalto, nephew of Sixtus V, enthusiastic about Bernini’s works in 1623, commissioned him to paint his own portrait and at the same time the famous statue of David; but he didn’t get to see it finished because before it was completed he died. Scipione Borghese immediately intervened and took over the order, thus managing to have another Bernini work for his villa.

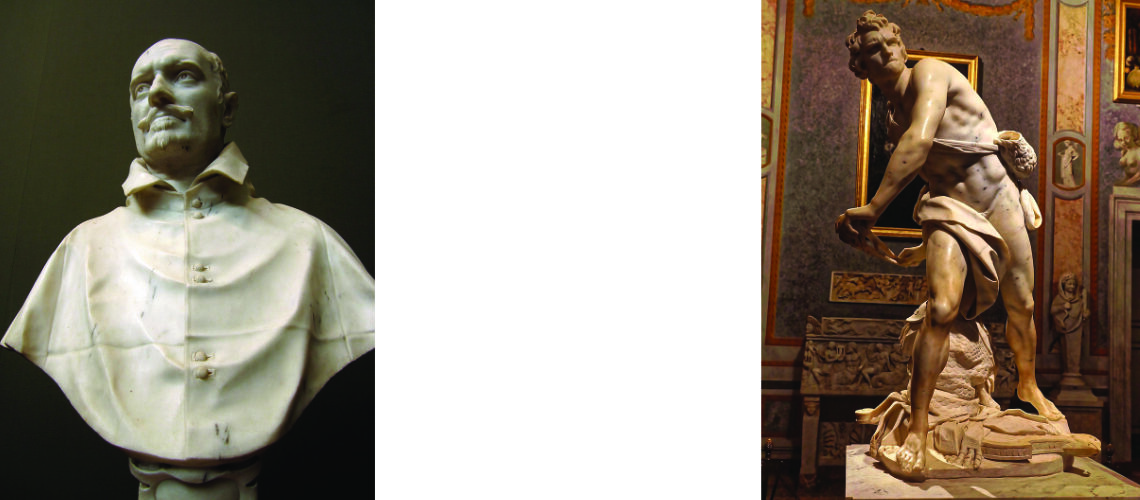

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, bust of Cardinal Montalto, 1623, Hamburg | Gian Lorenzo Bernini, David, 1624, Galleria Borghese, Rome |

Gian Lorenzo and his David

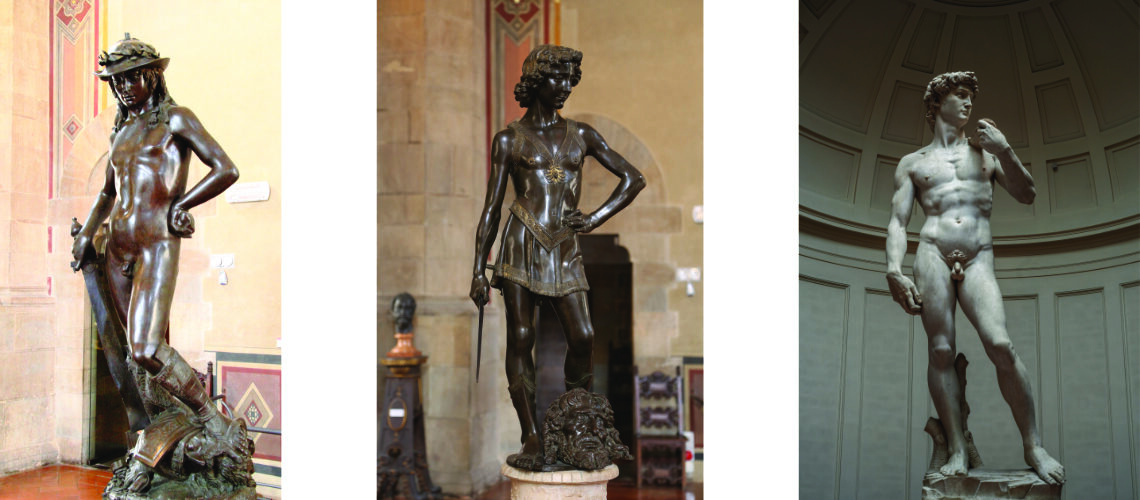

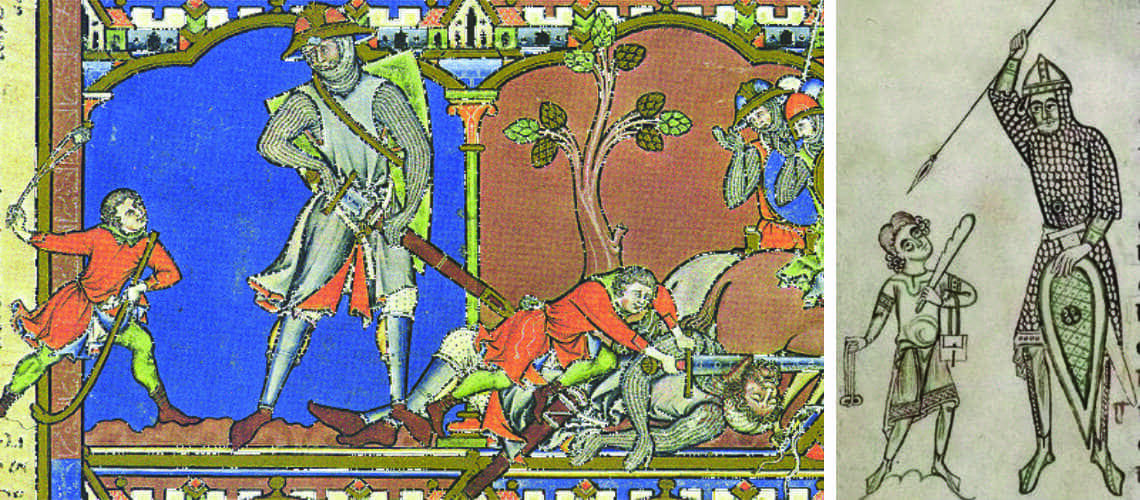

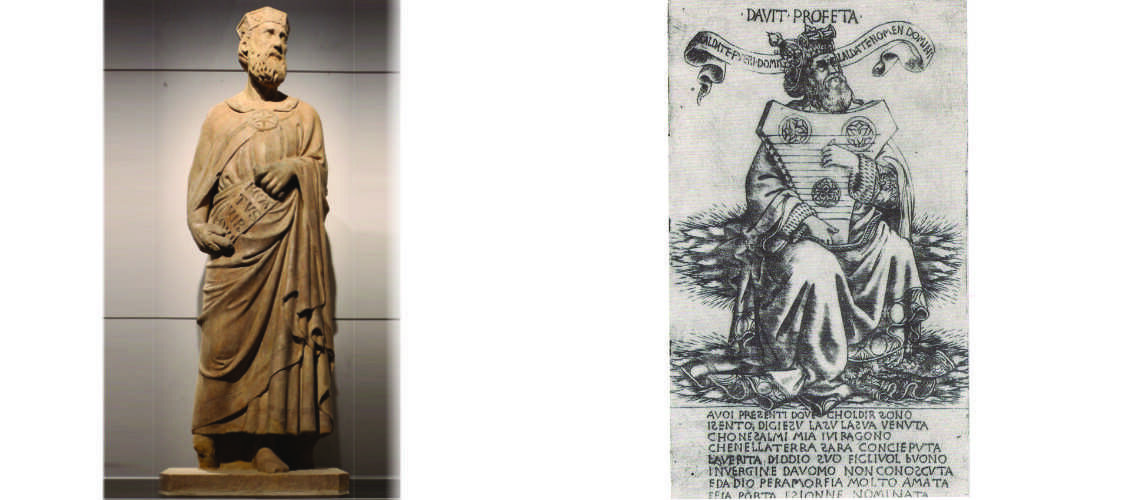

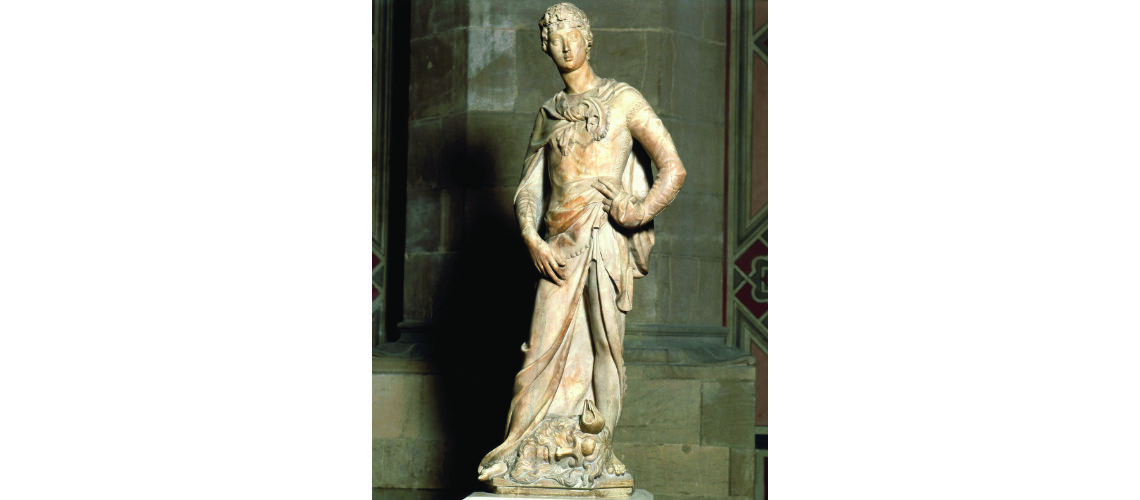

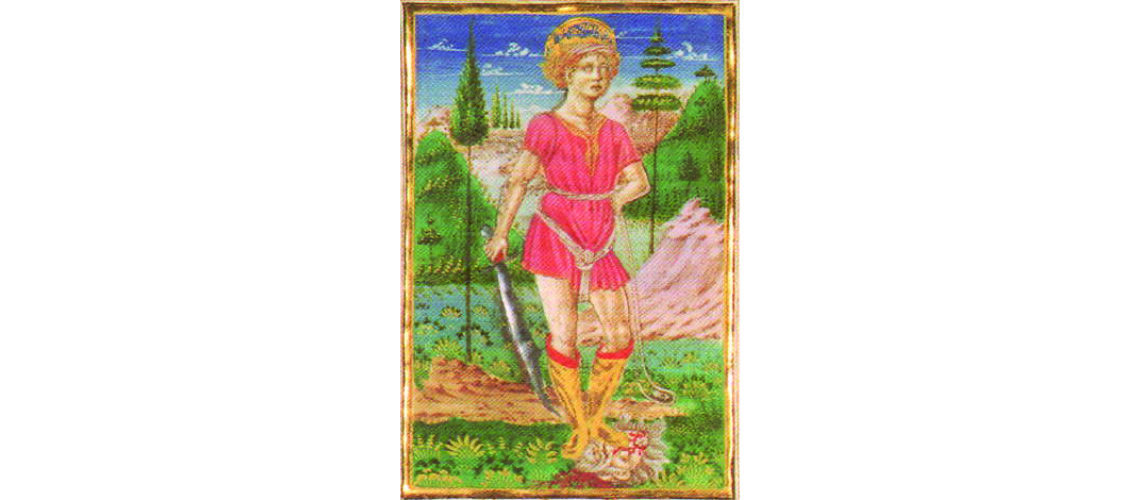

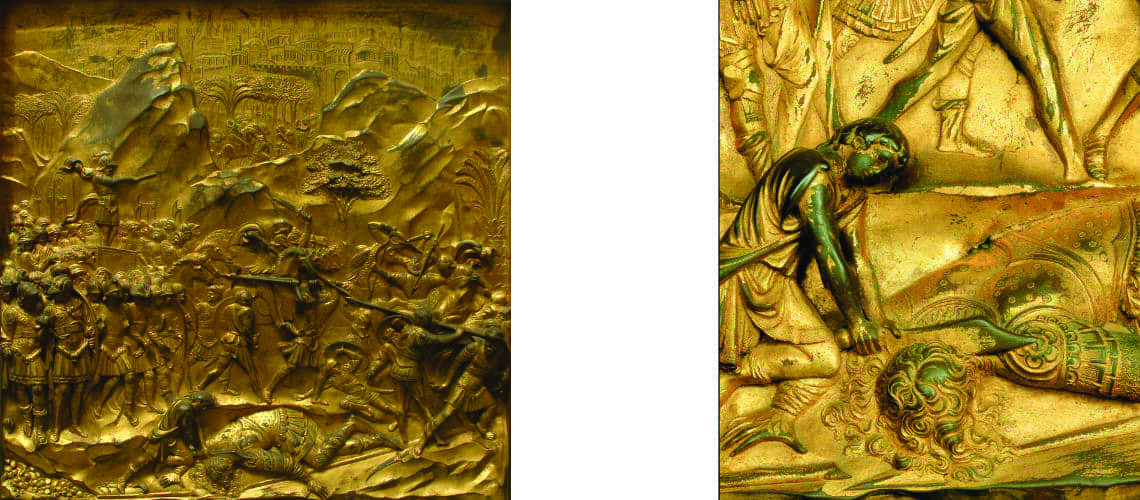

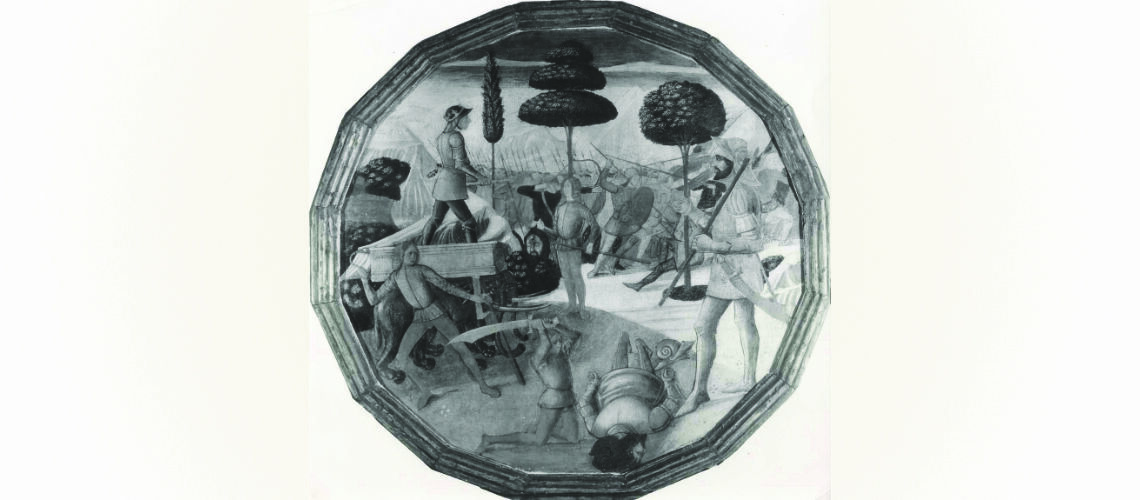

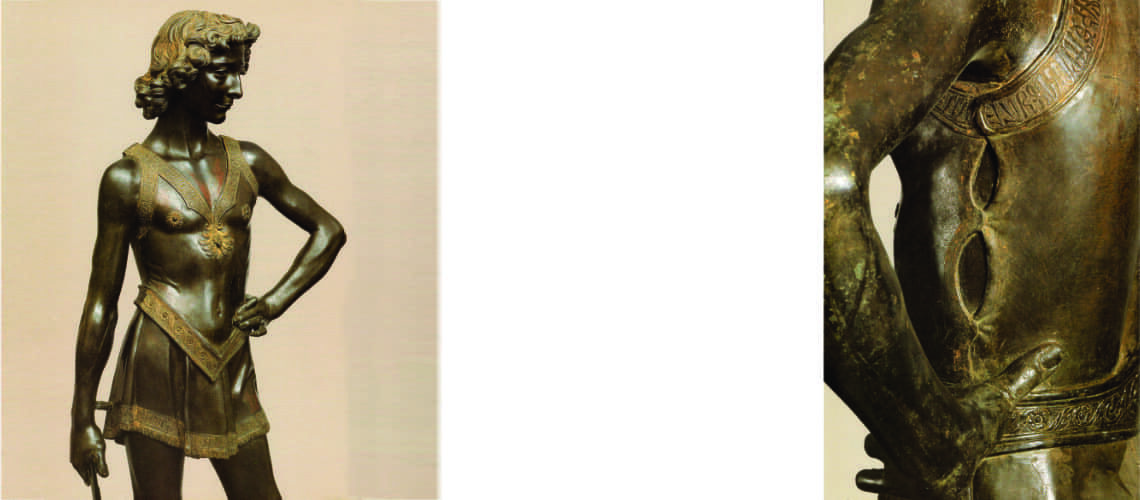

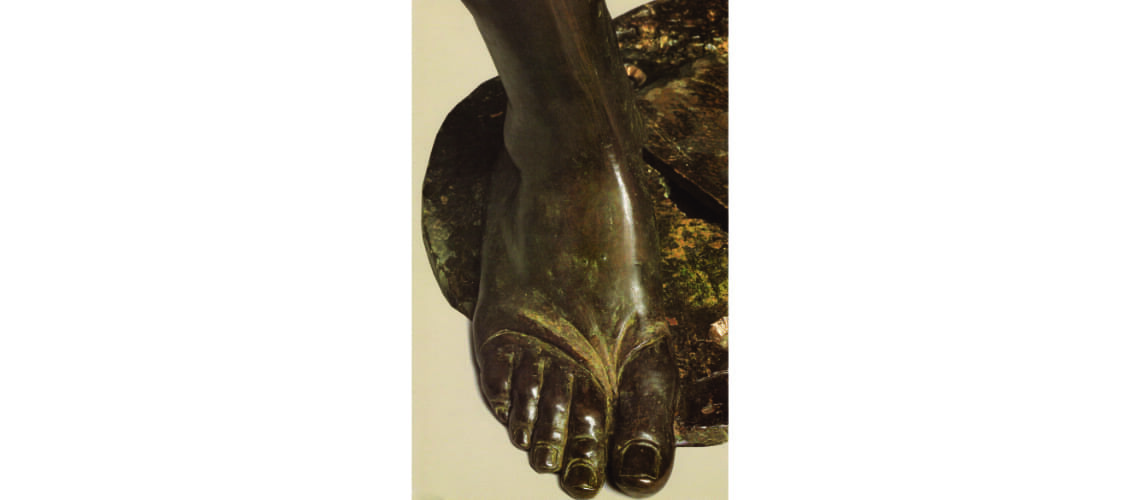

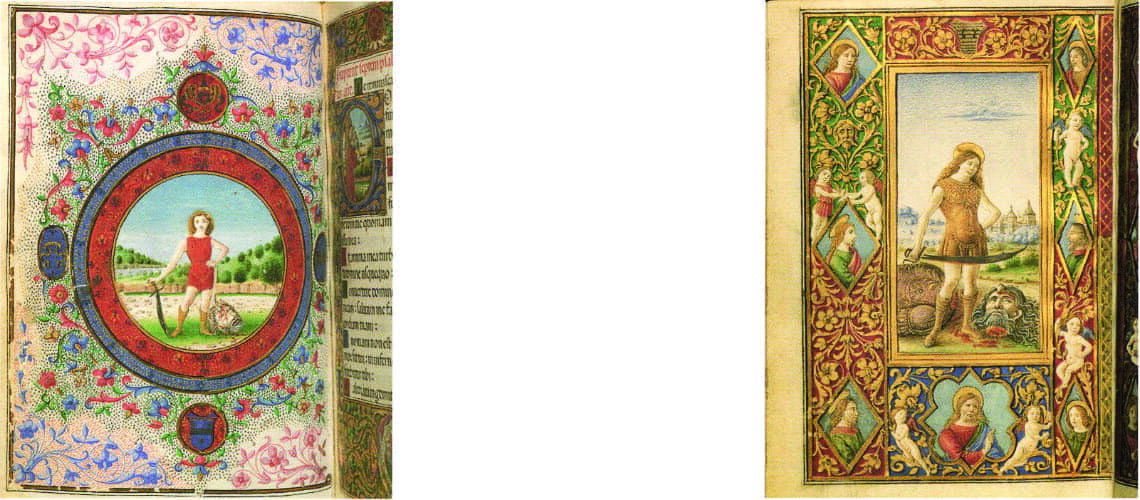

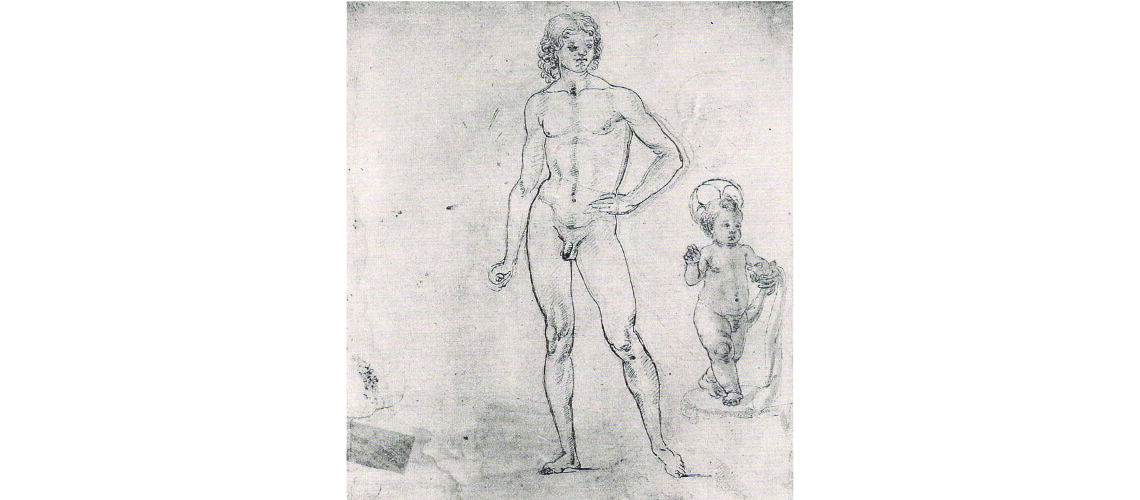

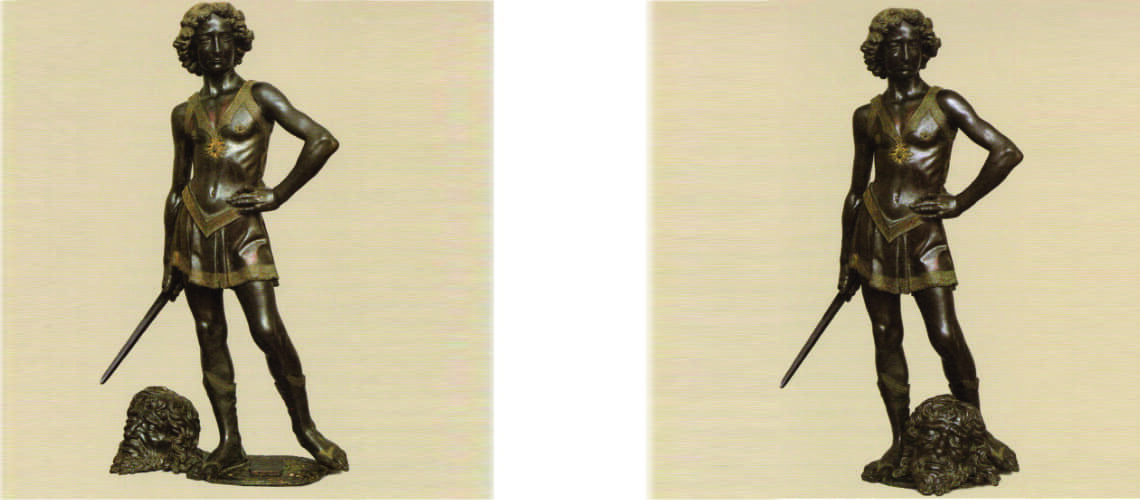

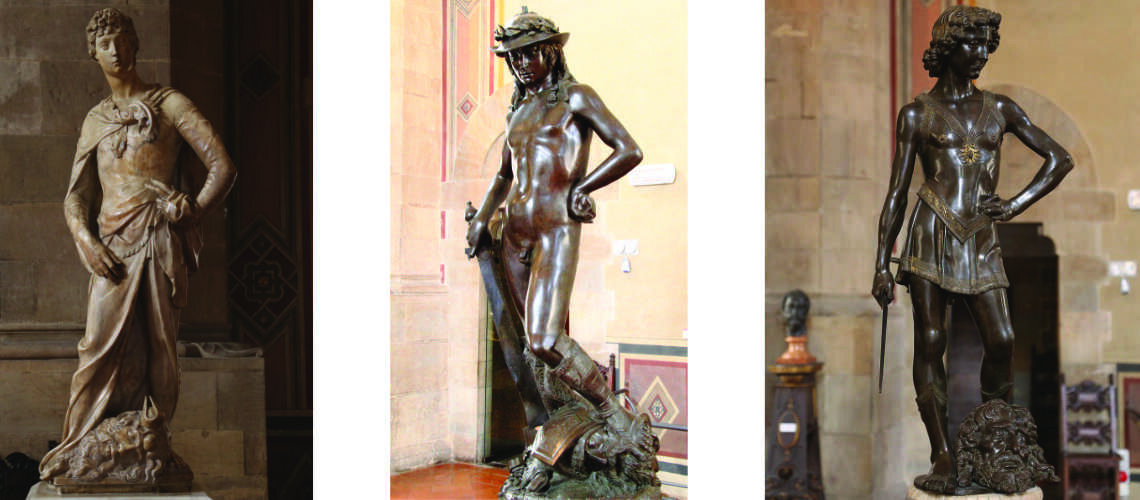

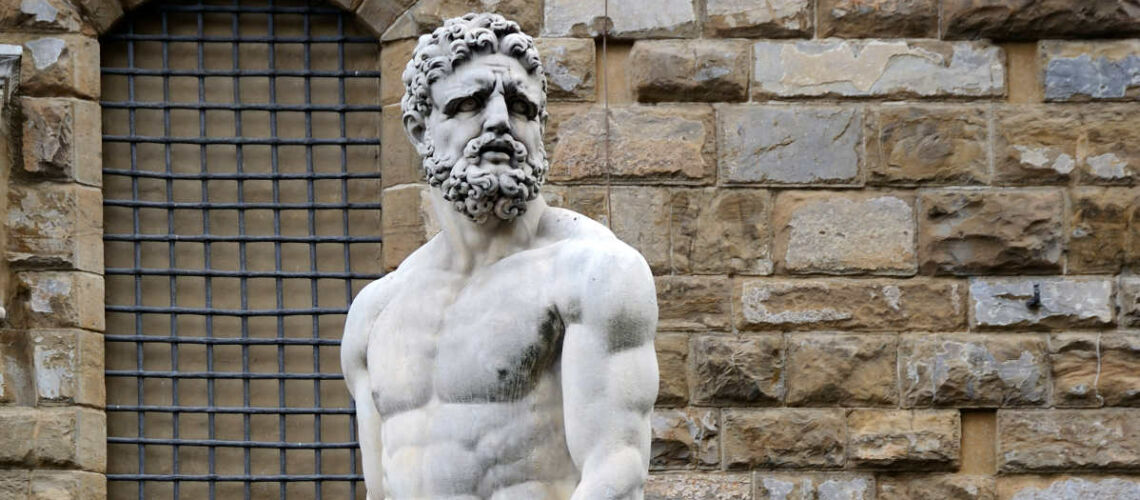

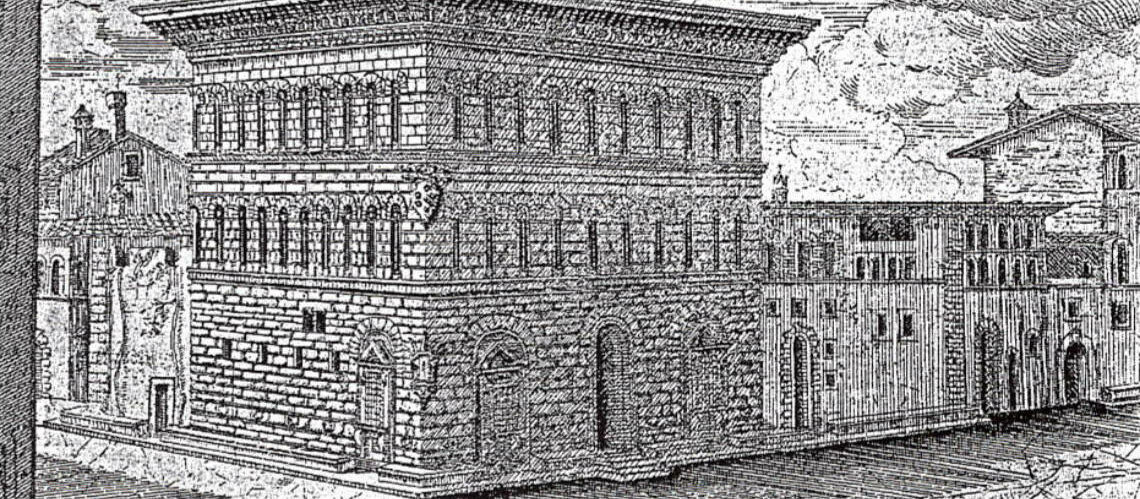

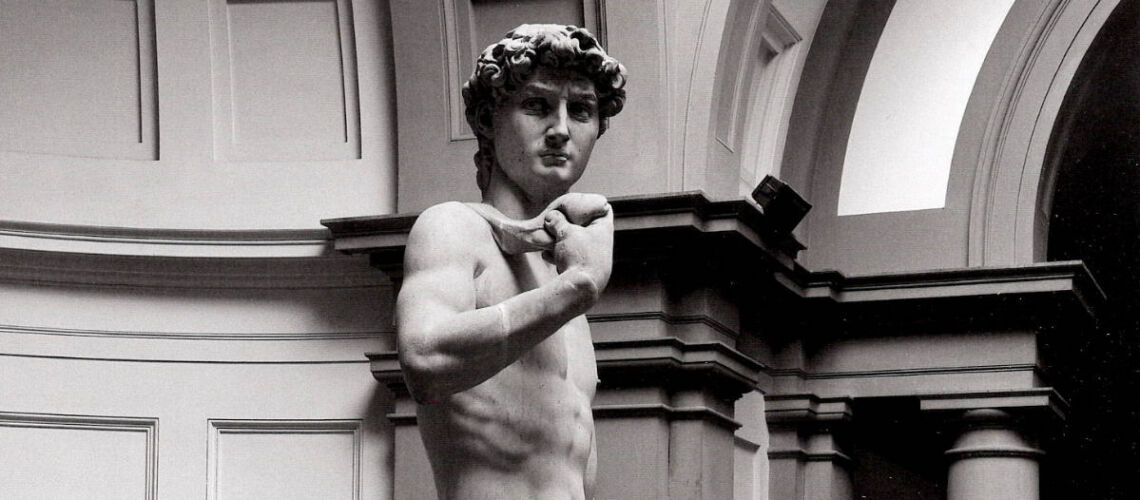

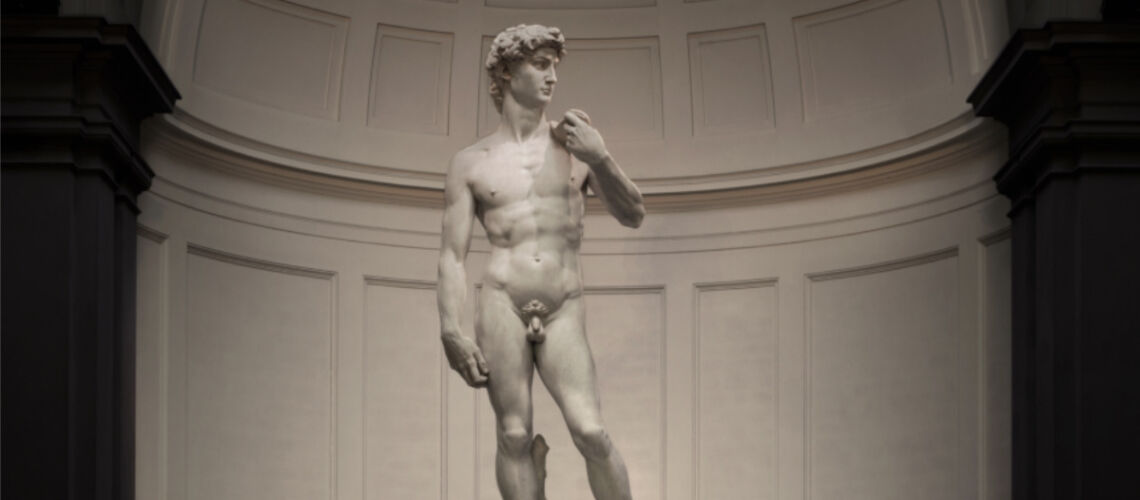

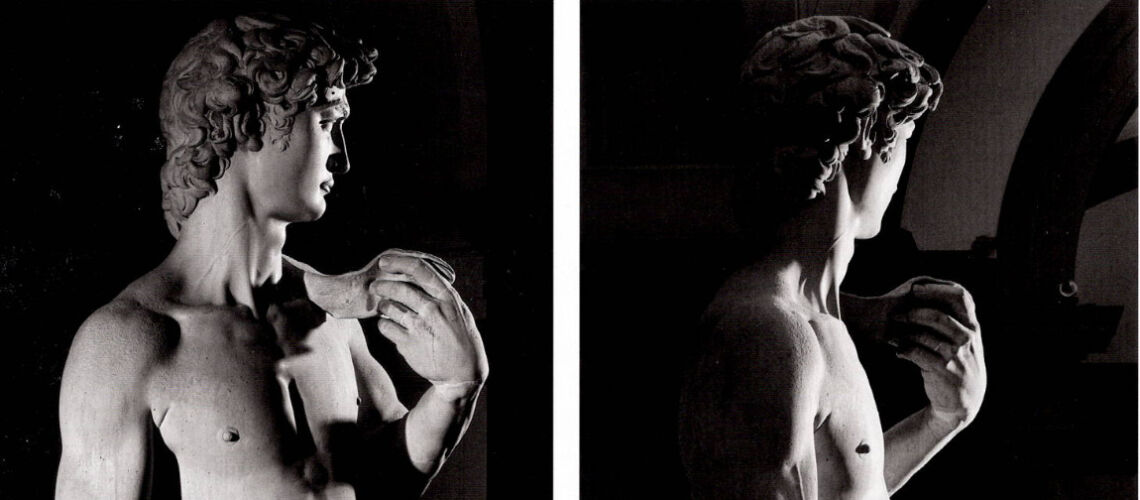

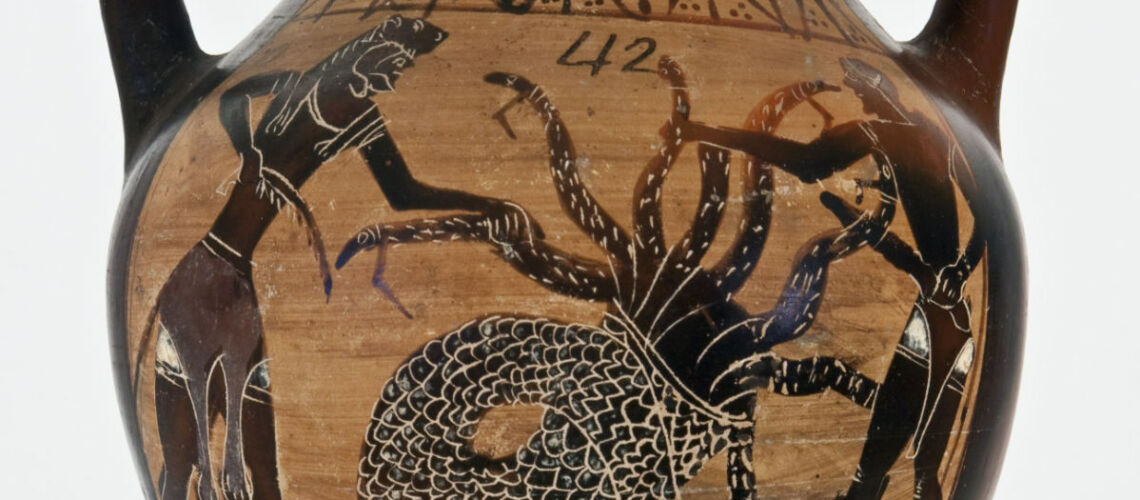

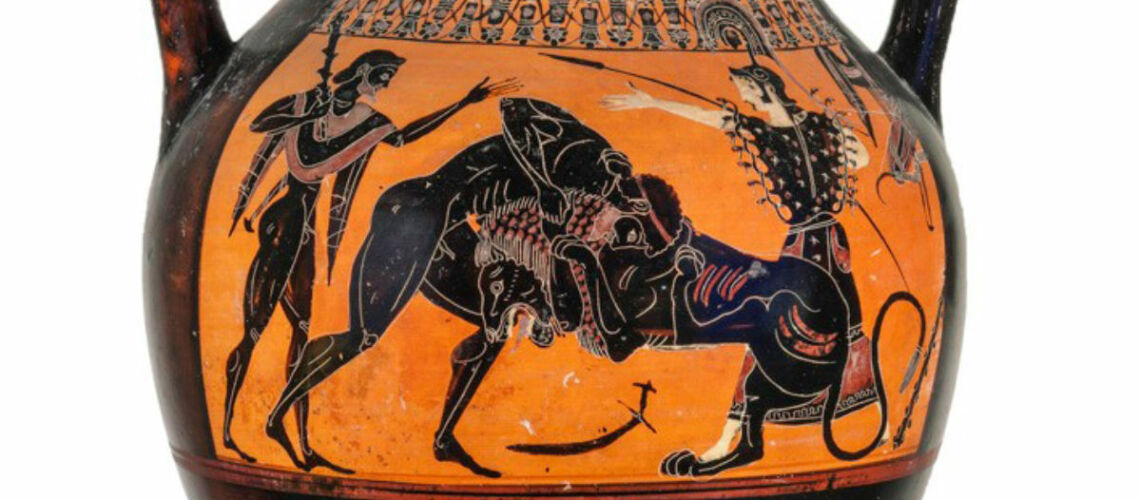

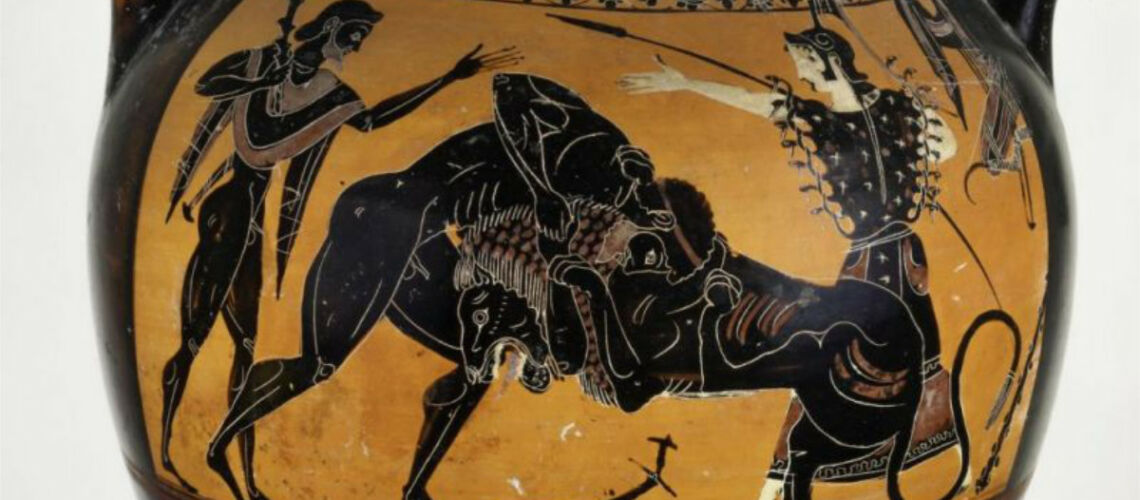

For this masterpiece, Bernini chose the moment of very high tension in which David is about to throw the stone on the head of the giant Goliath and not in the moment of triumph after Goliath has been beheaded, as happens in the two bronzes by Donatello and of Verrocchio; nor before the clash, as in Michelangelo, where David is concentrated before the launch. For all three of these earlier Renaissance figures a static and hieratic pose was chosen.

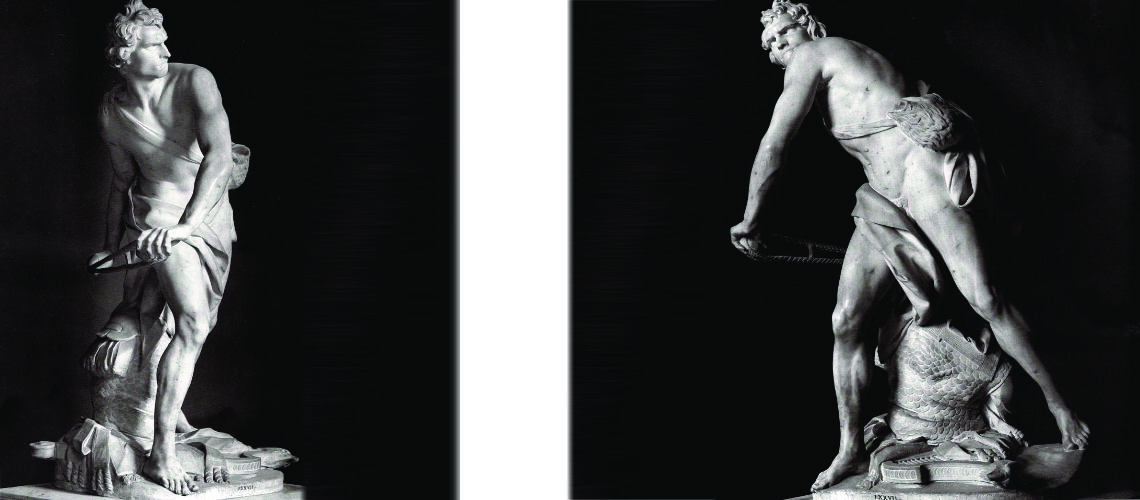

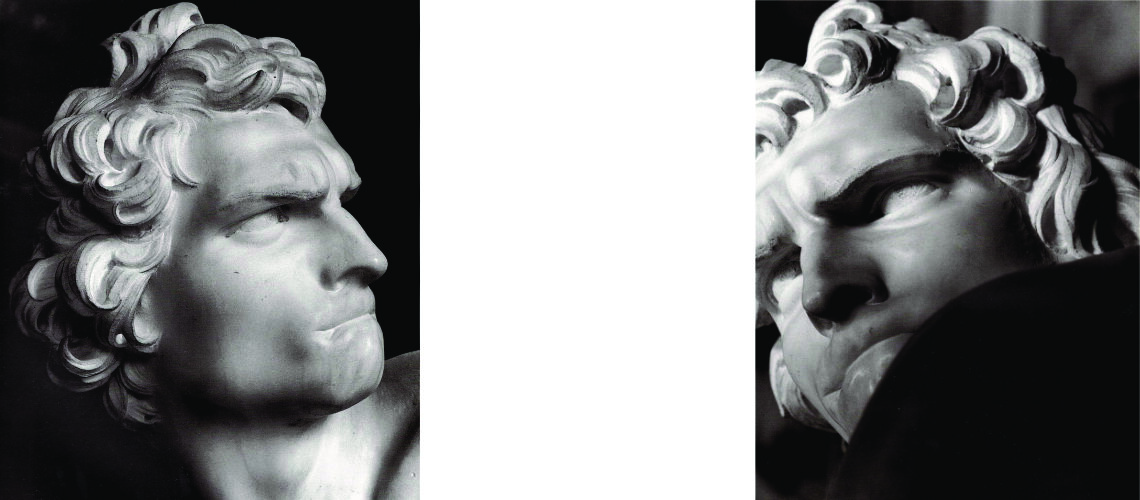

Instead, Bernini was able to highlight all the tension and effort of the shot in the twisting of his hero’s torso, which is also expressed with his frowning eyebrows and his forcefully squeezing his lips. On the ground is the armor that was hindering him and which he took off before the launch.

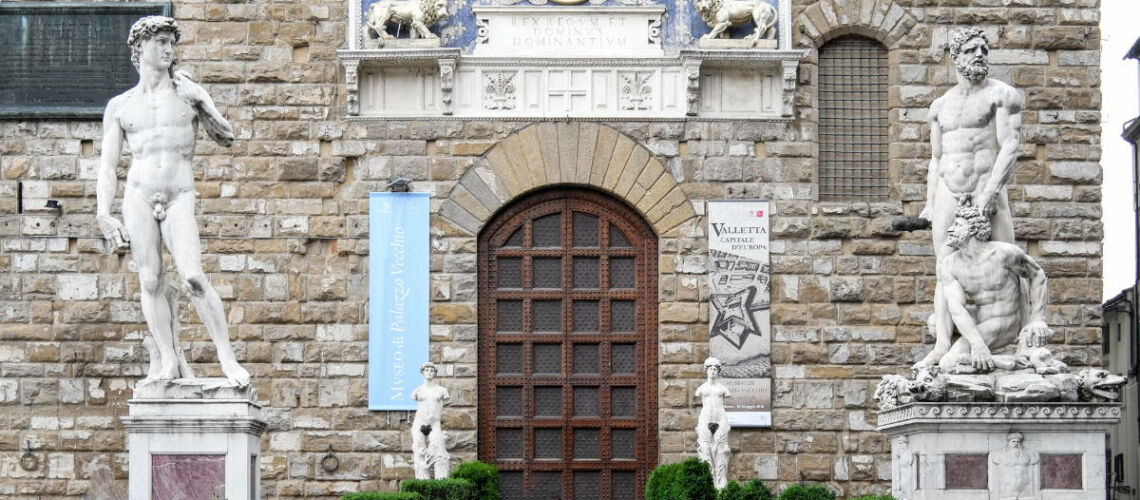

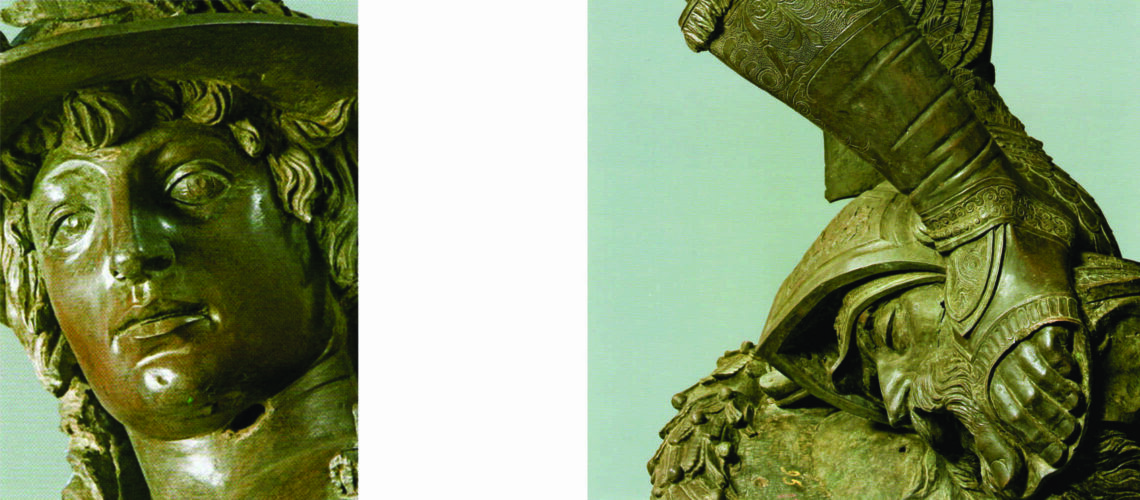

| Donatello, David, mid-15th century, Bargello Museum | Verrocchio, Donatello, 1475, Bargello Museum | Michelangelo, David, 1504, Accademia Gallery |

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, David, Galleria Borghese | Gian Lorenzo Bernini, David, Galleria Borghese |

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, David, Galleria Borghese, detail | Gian Lorenzo Bernini, David, Galleria Borghese, detail |

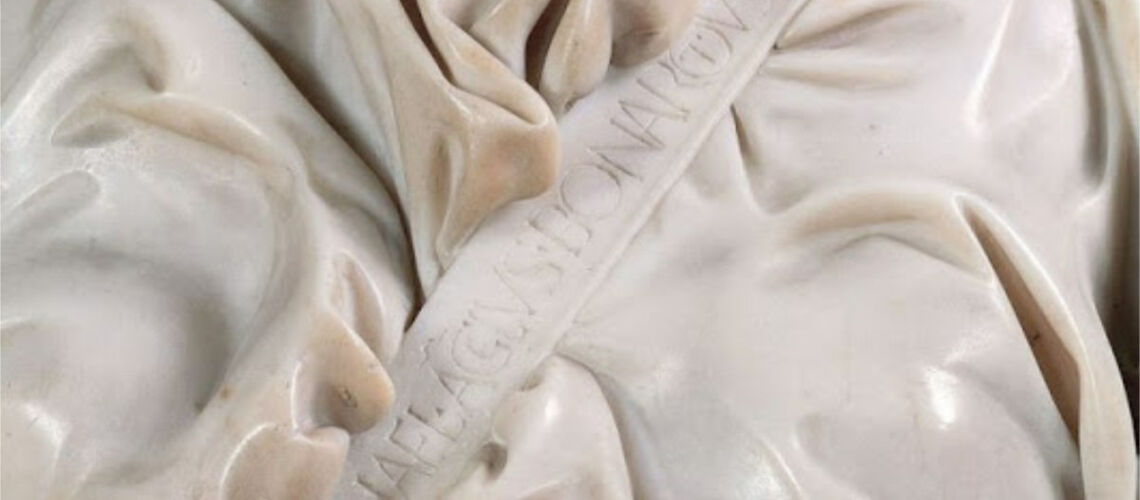

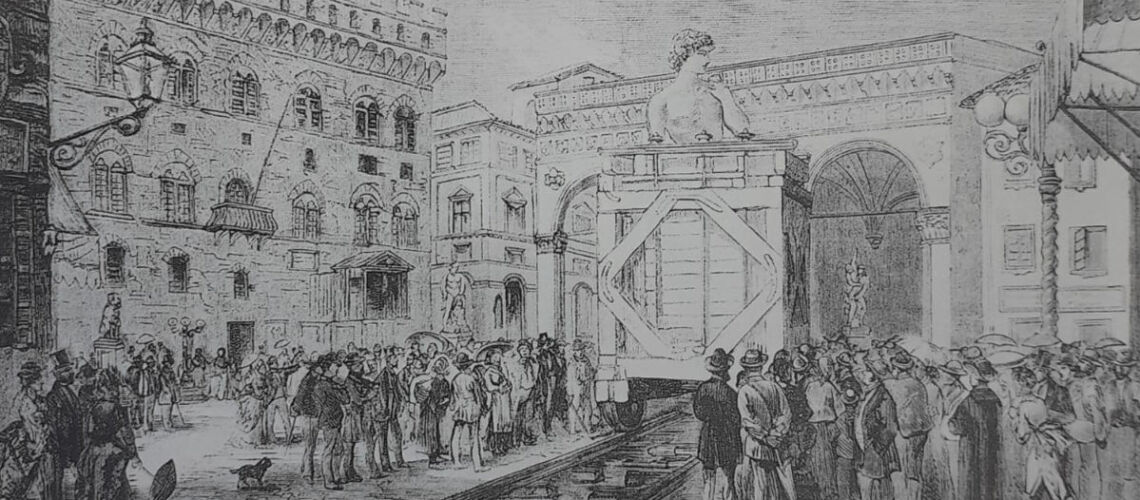

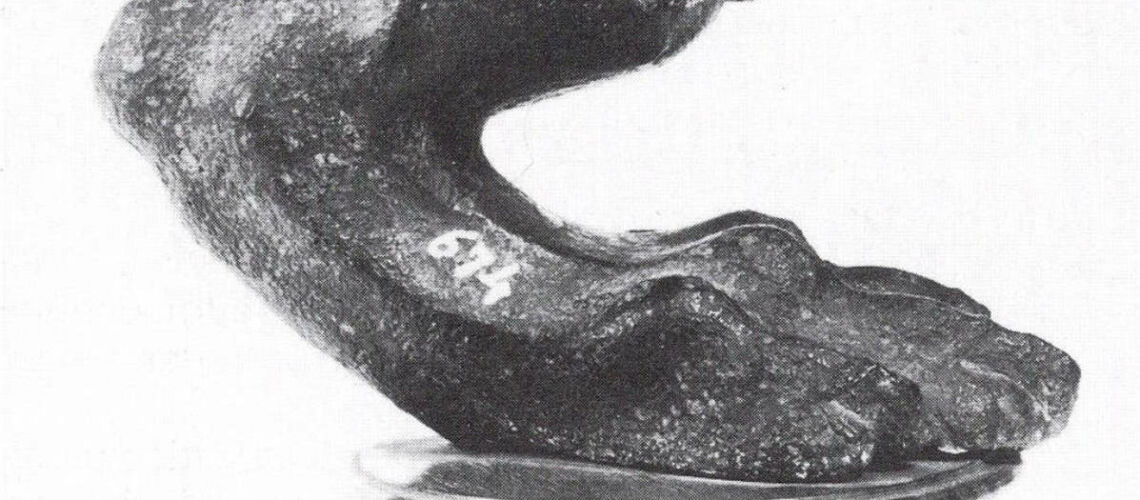

Posthumous lost wax bronze casting by the Ferdinando Marinelli Artistic Foundry on an original cast for the Pietro Bazzanti & Figlio Gallery in Florence.

With his David, Bernini manages for the first time to make the spectator feel surprise and fear, to involve him as if he were present in the challenge and action of overthrowing the giant Goliath, to make the biblical hero dramatically alive.

The Roi Soleil and Mussolini

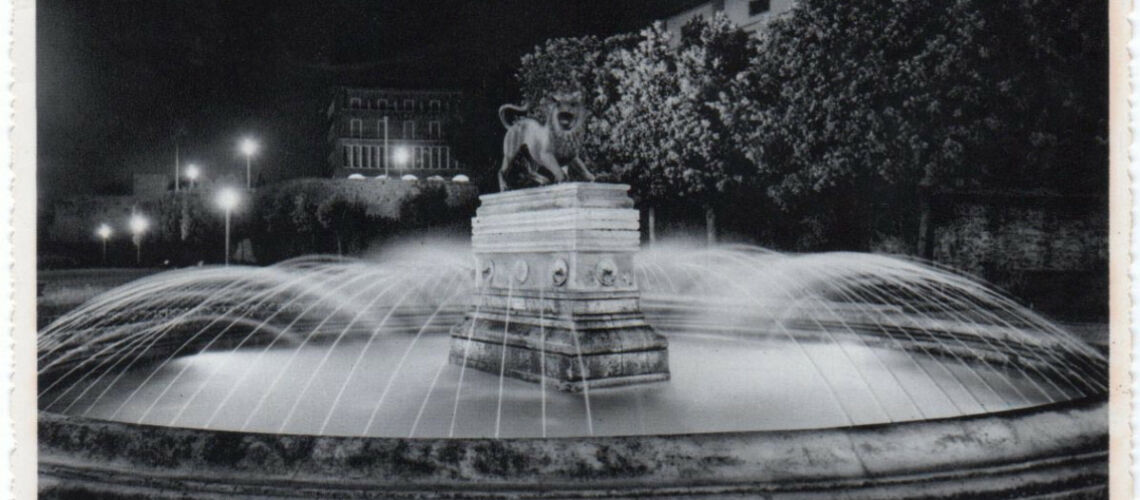

At the request of Benito Mussolini for his private collection, the Louvre Museum turned to the Ferdinando Marinelli Artistic Foundry to have the bronze replica of the sketch that Bernini made in 1678 for the equestrian monument of Louis XIV; the sketch was taken to the foundry where the negative mould and a posthumous lost wax bronze casting were made. After the war the casting returned to the Louvre.

| Terracotta sketch by Gian Lorenzo Bernini for the equestrian monument of Louis XIV | Posthumous casting by the Ferdinando Marinelli Artistic Foundry of the terracotta sketch by Gian Lorenzo Bernini for the Equestrian Monument of Louis XIV, Louvre Museum |

Posthumous lost wax bronze casting by the Ferdinando Marinelli Artistic Foundry on an original cast for the Pietro Bazzanti Gallery in Florence