THE OTHER BYZANTINE DOORS IN ITALY

The series of Byzantine doors made in Constantinople (wood covered with inlaid bronze panels, frames, and handles) continued after the first one was donated to the Cathedral of Amalfi in 1060 by the merchant Mauro di Pantaleone of Amalfi:

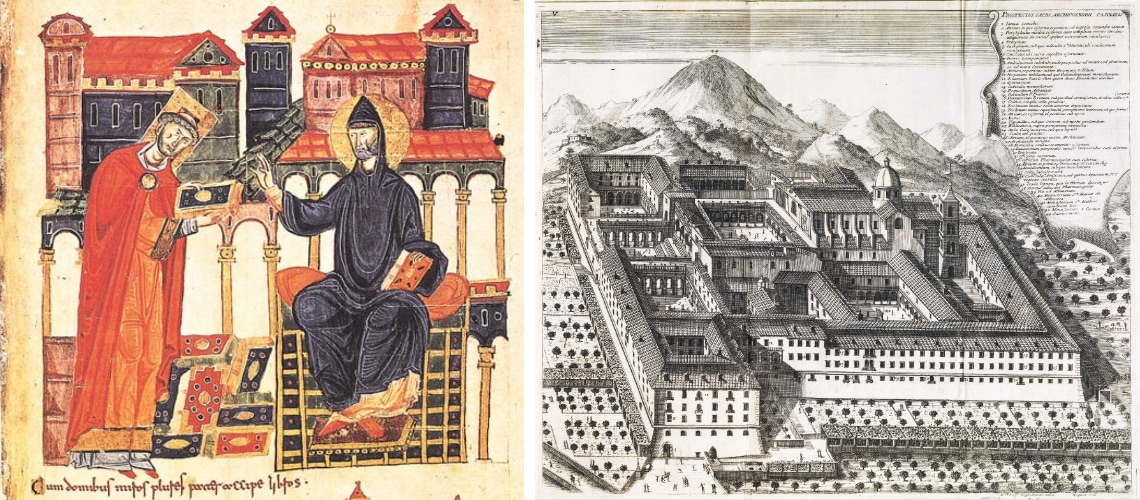

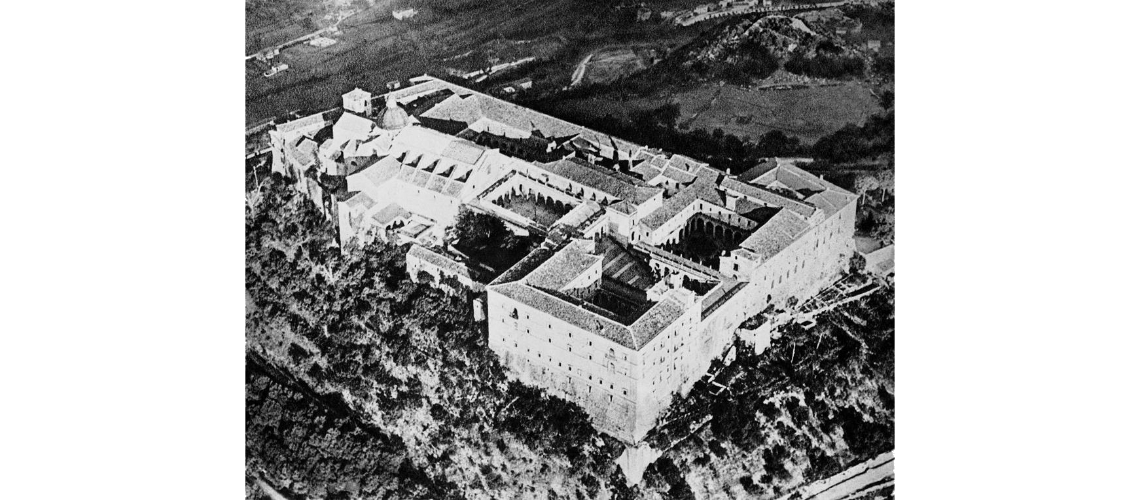

In 1066, Abbot Desiderius of Montecassino requested a similar door for the church of Montecassino, whose consecration in 1071 was attended by the famous Hildebrand of Soana, abbot of St. Paul Outside the Walls in Rome, Alfano, bishop of Salerno, and Giraldo, archbishop of Siponto and St. Michael the Archangel on the Gargano Peninsula.

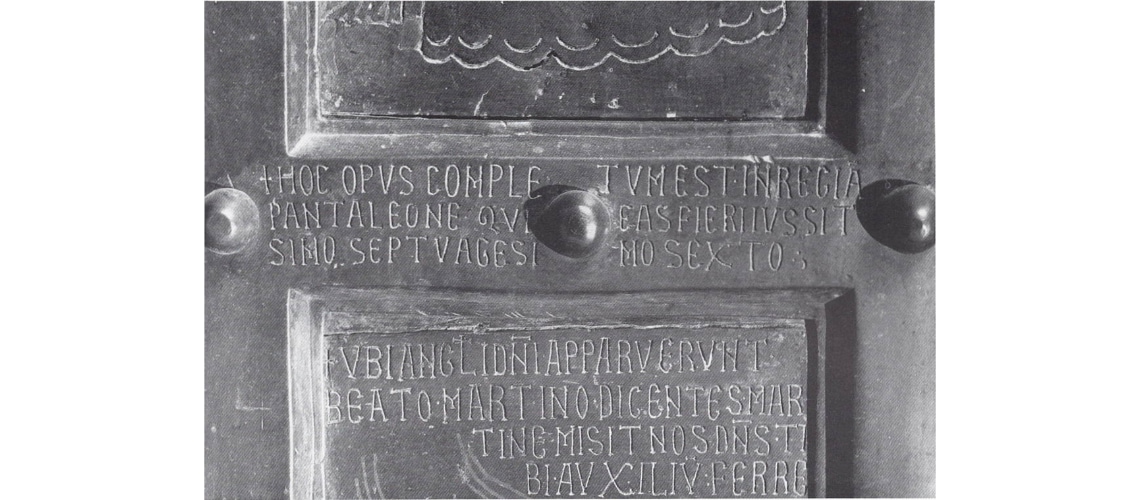

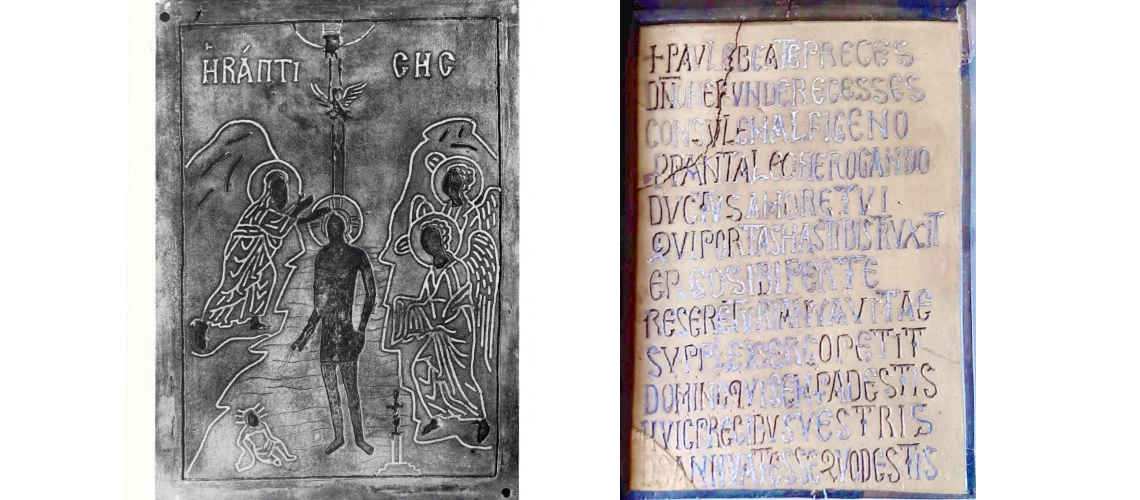

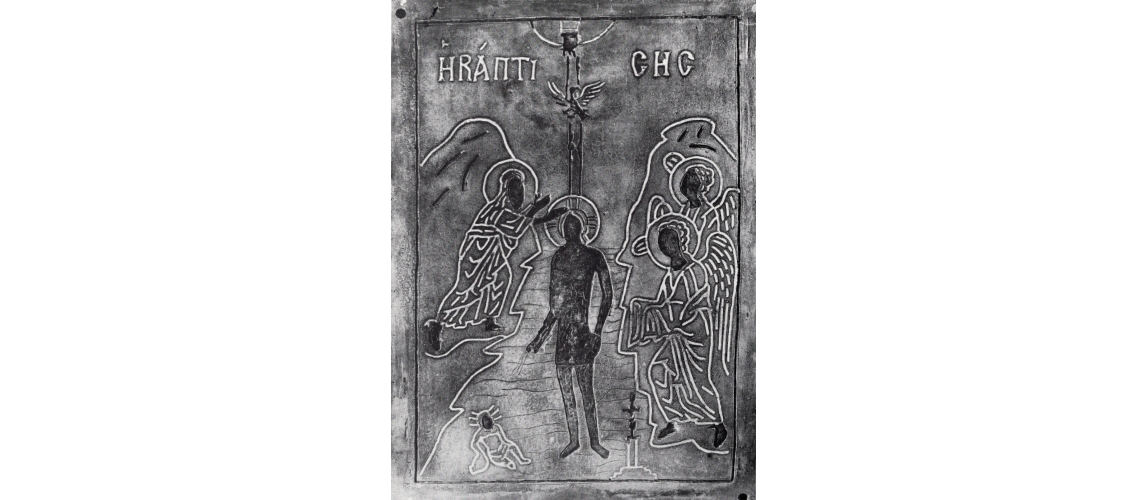

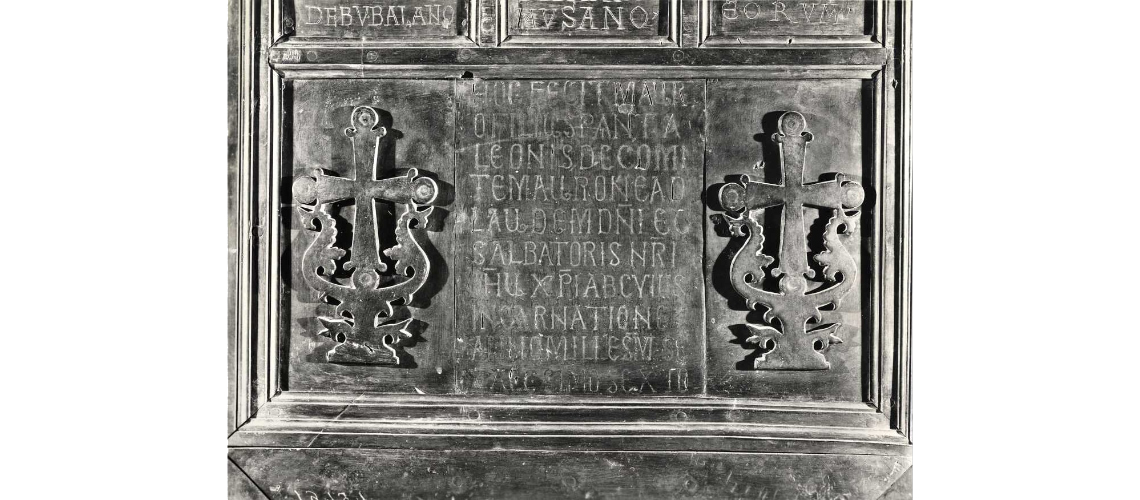

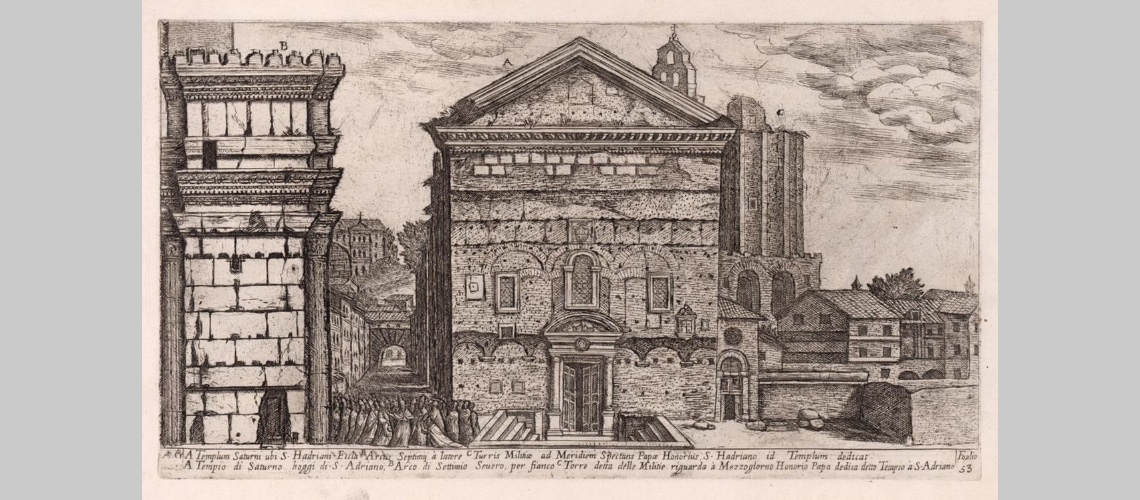

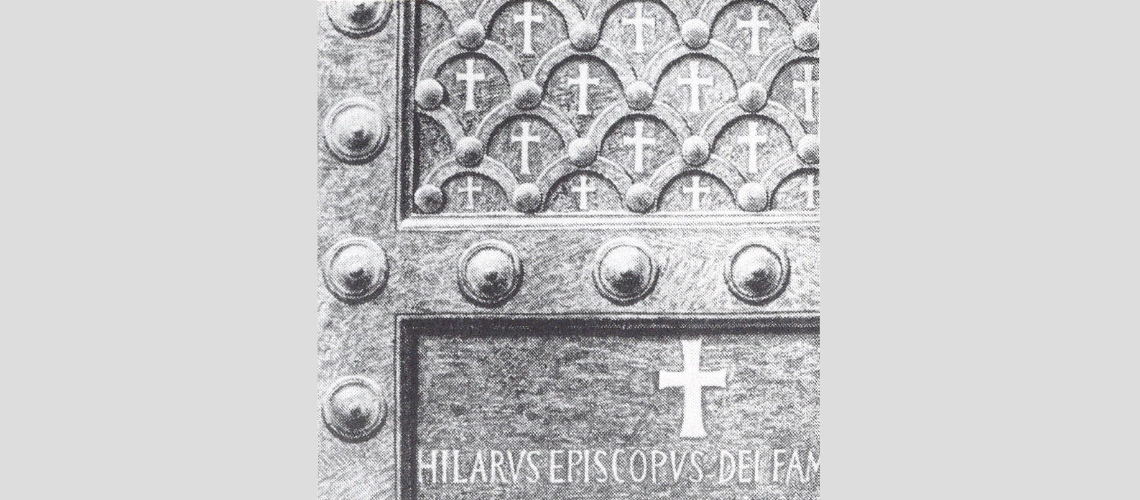

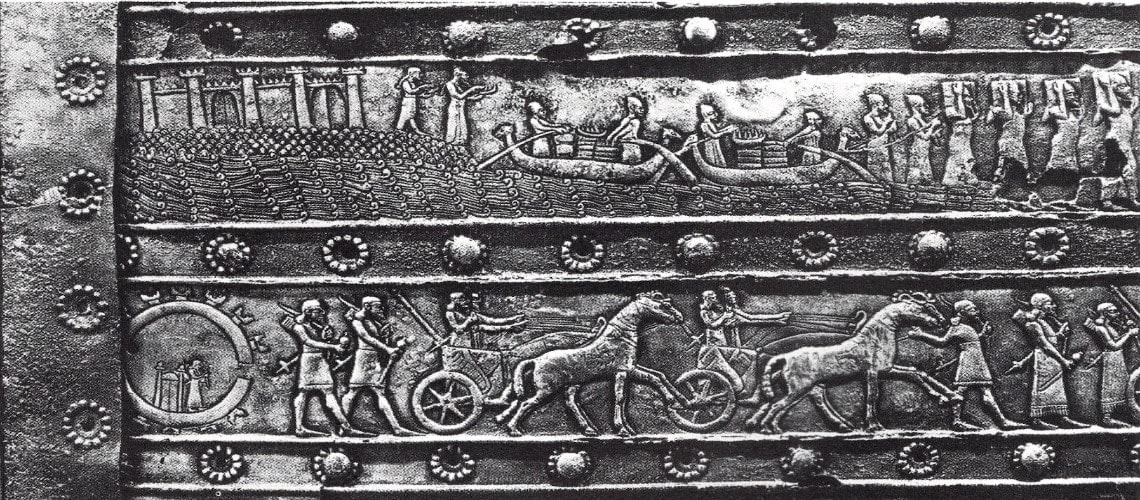

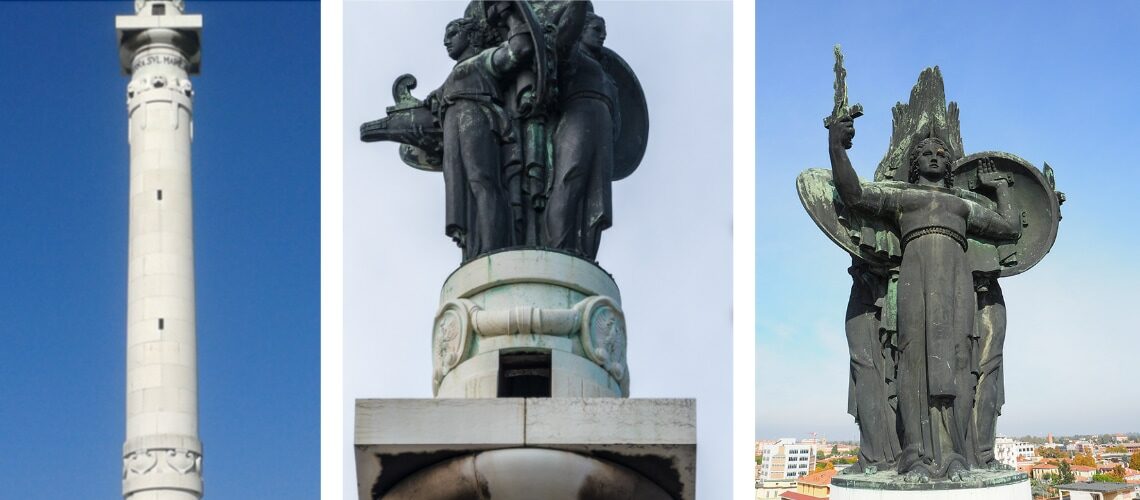

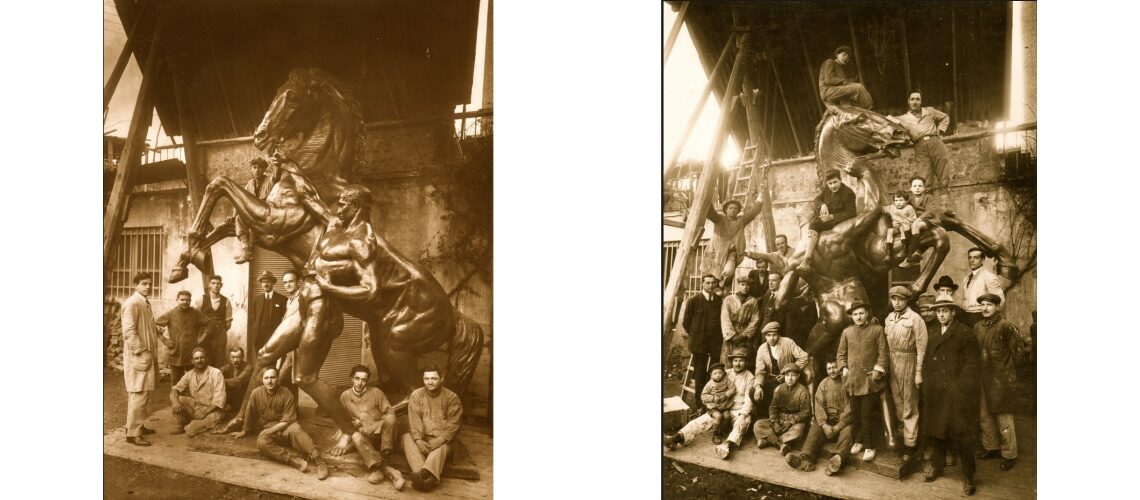

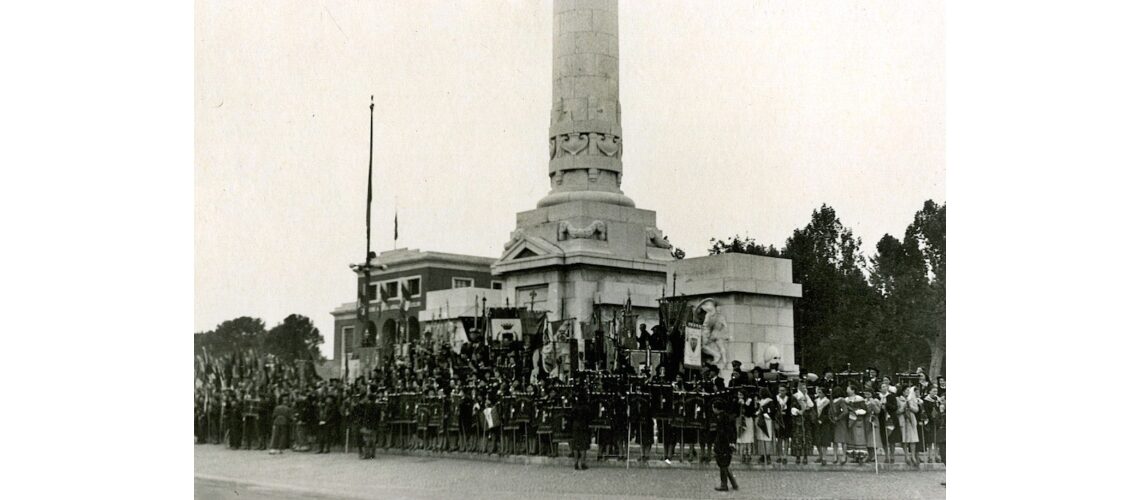

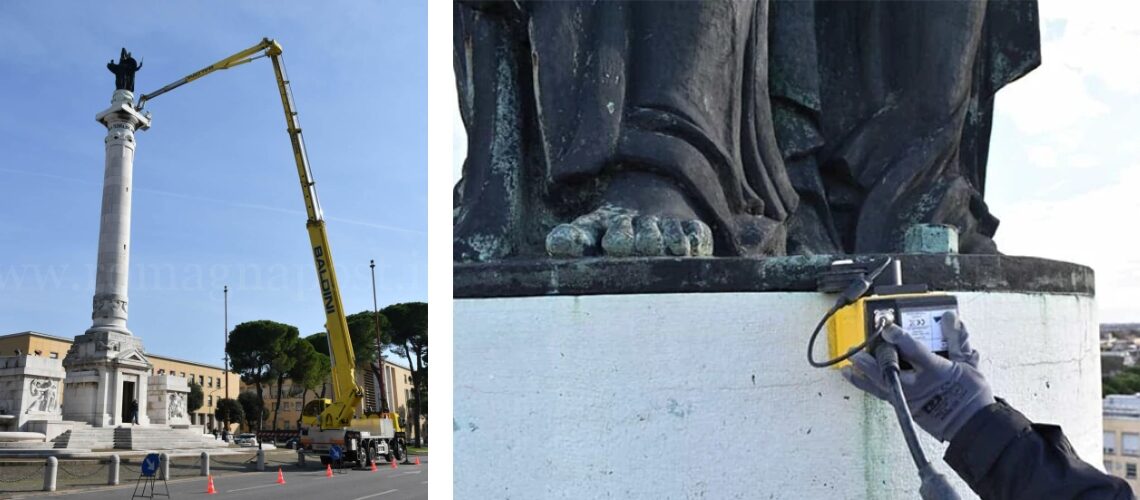

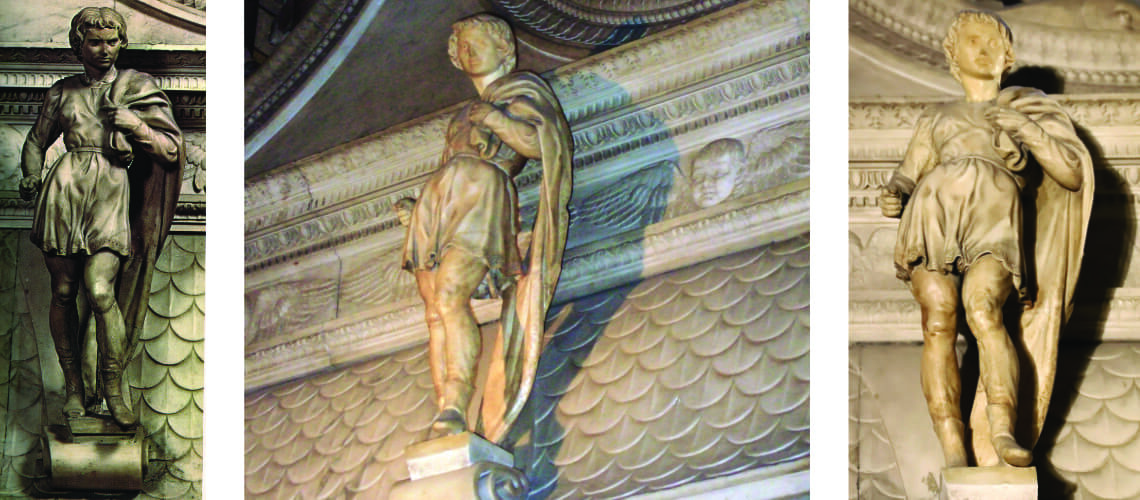

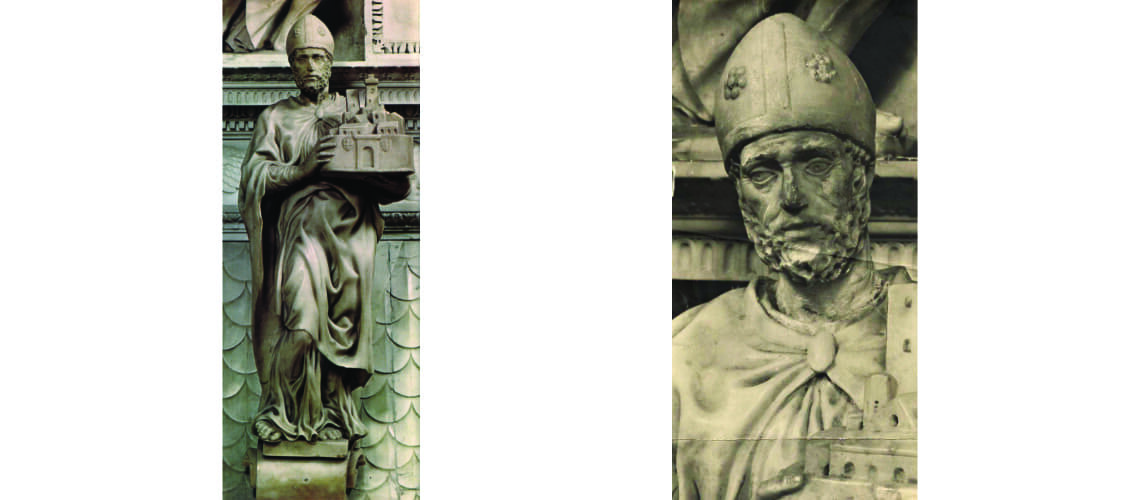

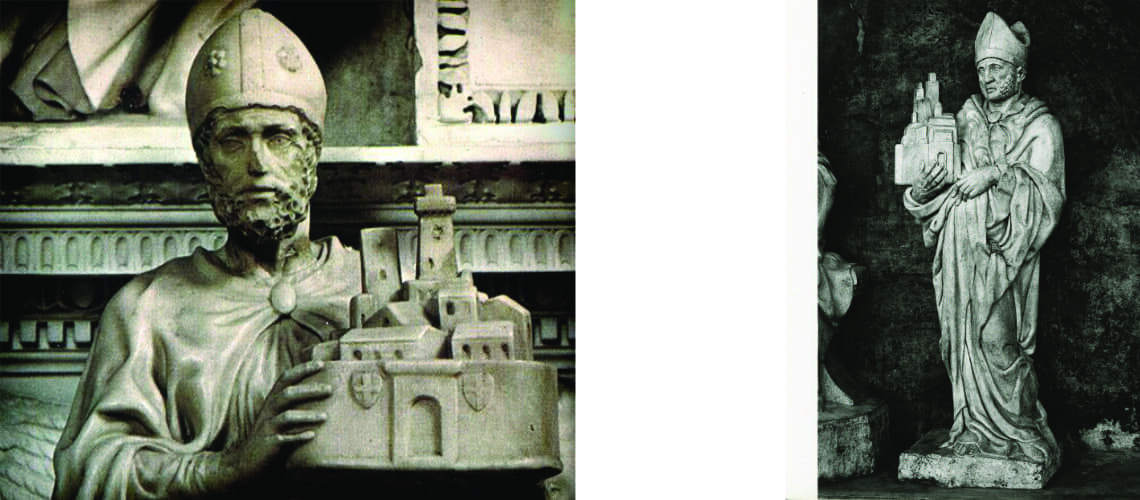

Giraldo’s presence at the Montecassino ceremony led to the request for a similar door for the sanctuary of San Michele al Monte Sant’Angelo, a door that was “ordered” in Constantinople in 1076 by Mauro di Pantaleone, as reported by the inscription on the door itself: HOC OPUS COMPLETUM EST IN REGIAM URBEM COSTANTINOPOLI ADIUBANTE DOMINO PANTALEONE QUI EAS FIERI IUSSIT ANNO AB INCARNATIONE DOMINI MILLESIMO SEPTUAGESIMO SEXTO. [Photos 1 to 10, bronze door of the Sanctuary of San Michele al Monte Sant’Angelo and details of the same]

| 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 4 | 5 | 6 |

7

8

| 9 | 10 |

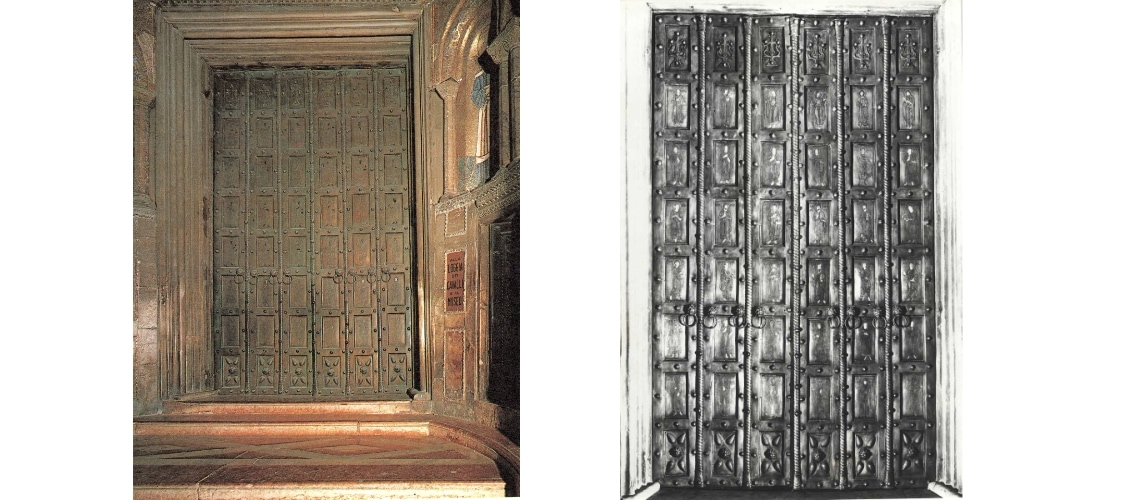

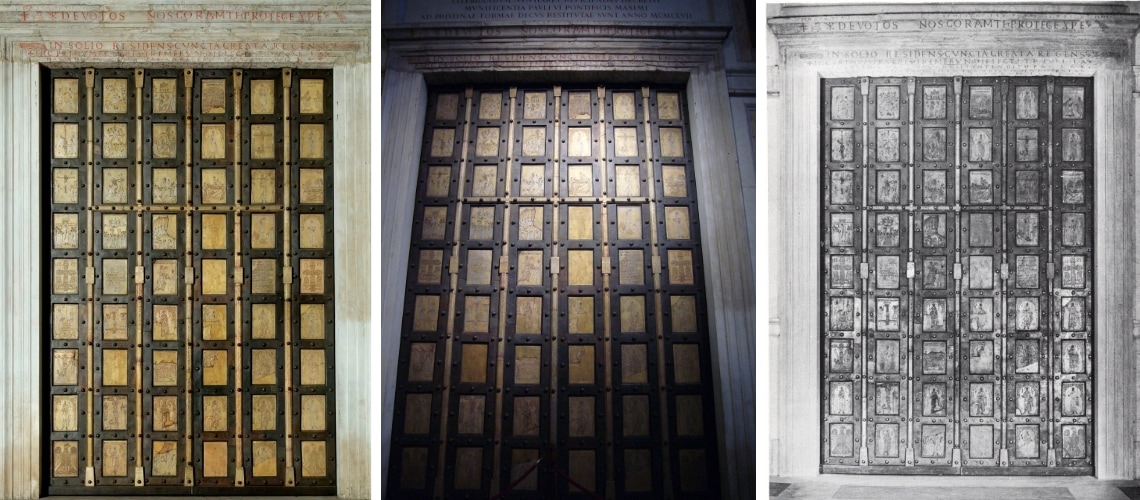

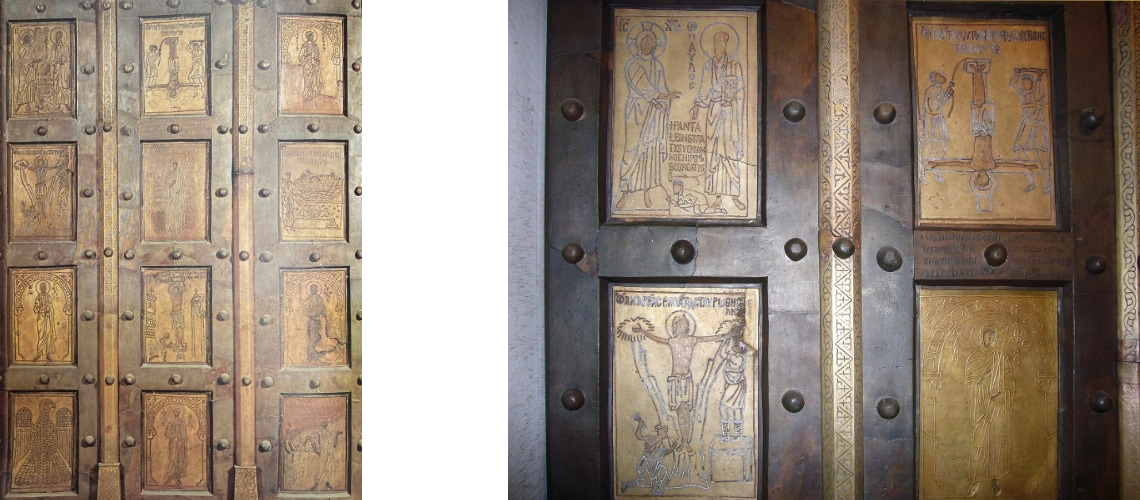

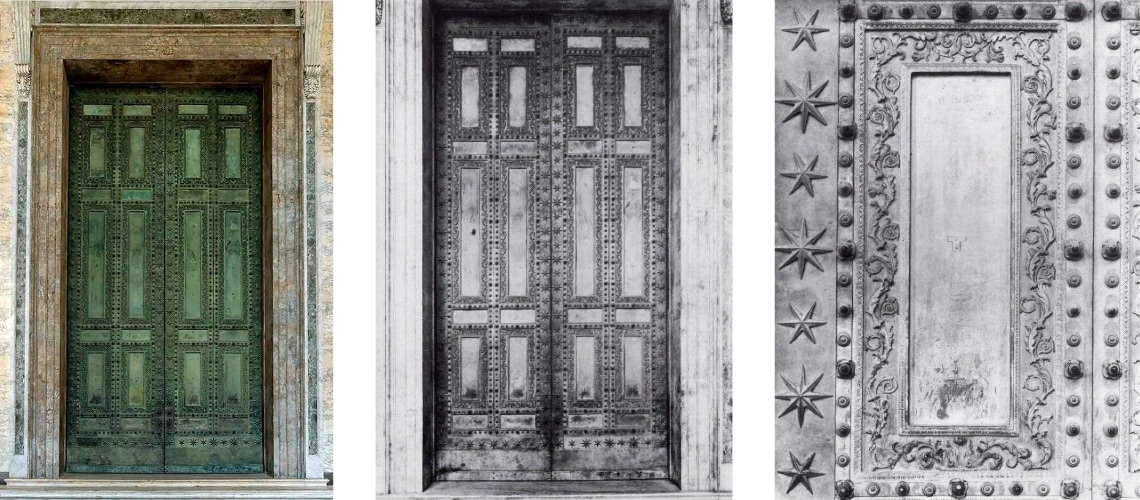

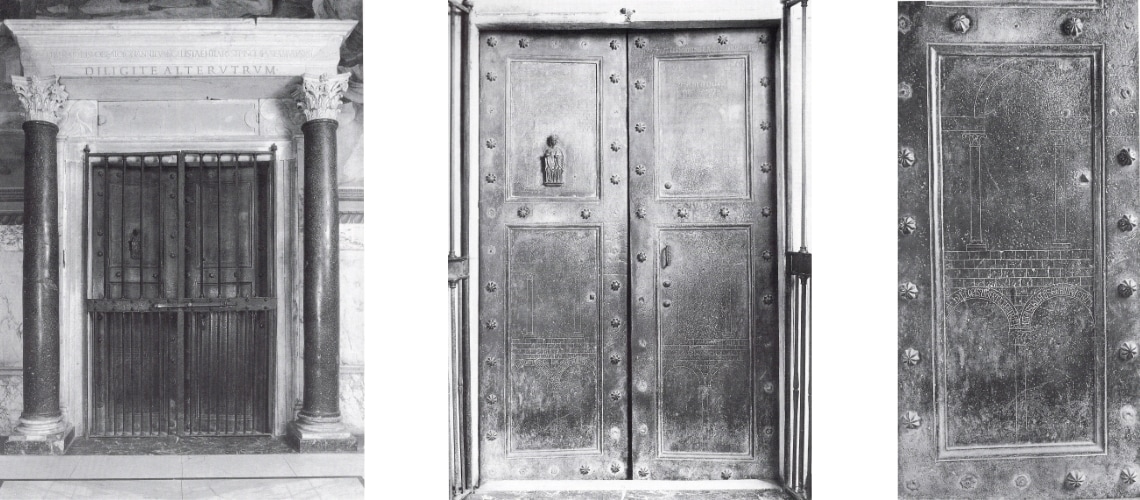

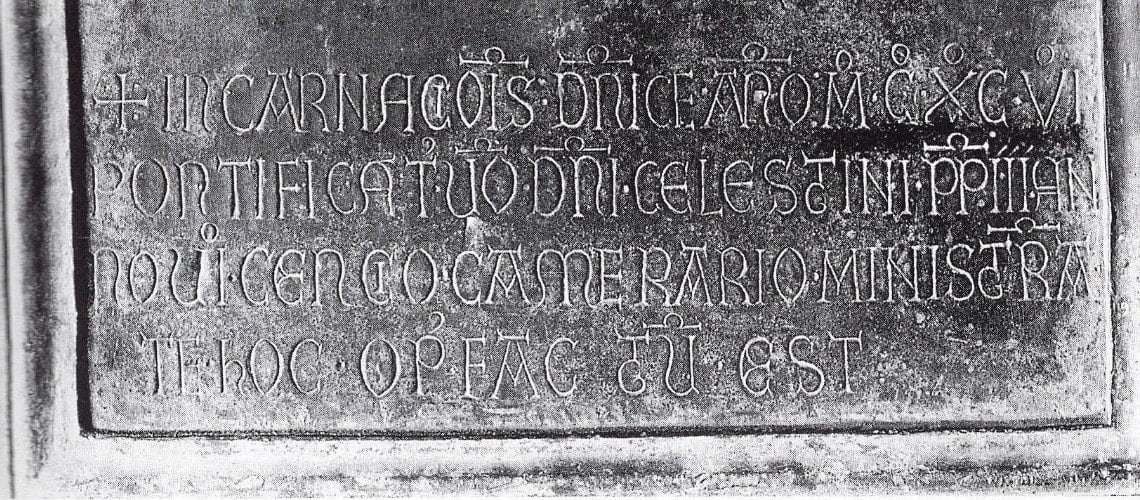

Around 1070, at the request of Ildebrando di Soana and commissioned by Mauro di Pantaleone of Amalfi, the Door of St. Paul Outside the Walls in Rome was built in Constantinople by Theodoros and Staurachios. [Photos 11–16, bronze door of the Papal Basilica of St. Paul Outside the Walls, Rome, and details of the doors]

| 11 | 12 | 13 |

14

| 15 | 16 |

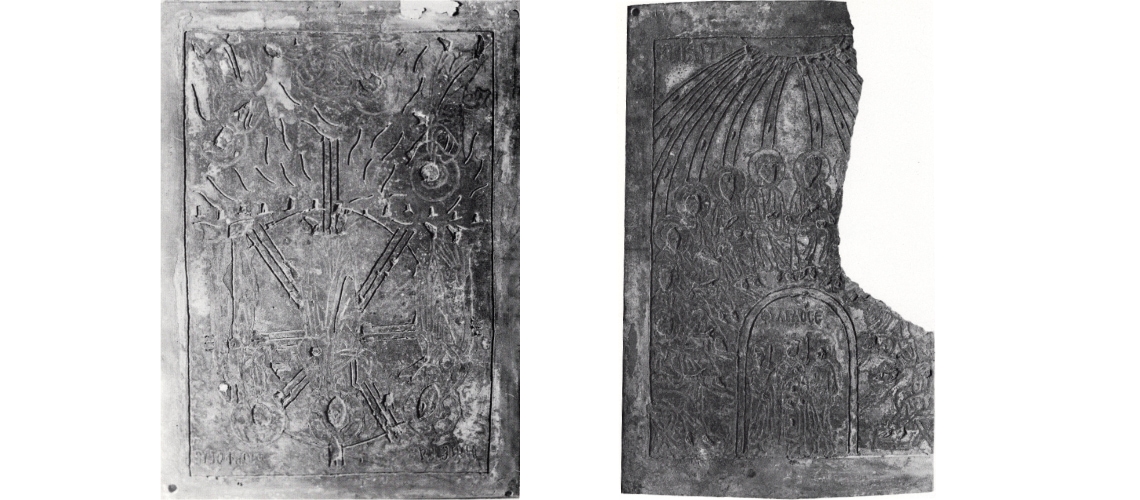

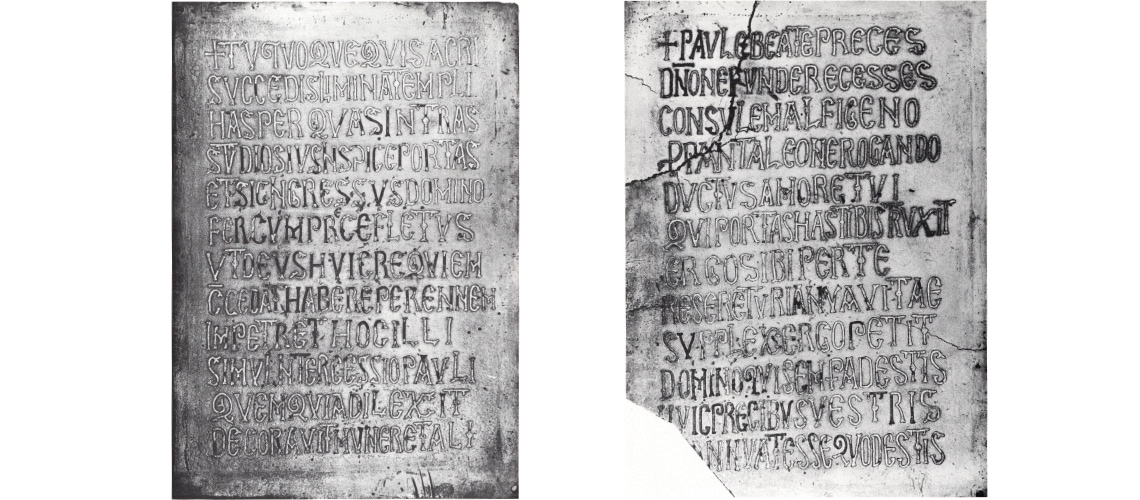

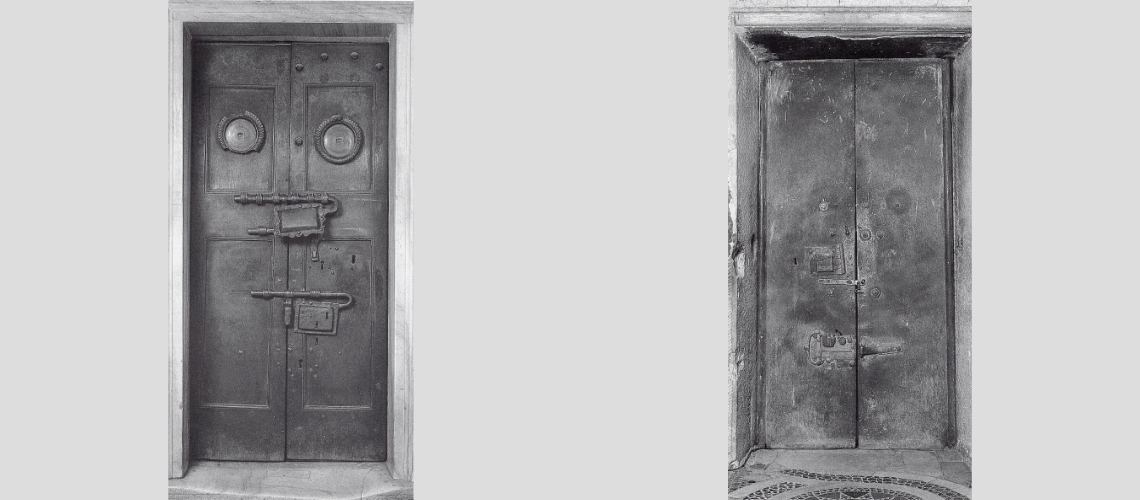

On the Atrani door, only the four central panels feature Byzantine damascening; the others feature a sort of identical, low-relief chalice from which a cross emerges, probably cast with sand and held in place by four large studs. One of the damascened panels bears the name of the donor Pantaleone, while the other features Greek inscriptions indicating it was made in Constantinople in 1087. [Photos 17 to 21, bronze door of the Church of San Salvatore de’ Birecto in Atrani and details thereof]

| 17 | 18 |

19

| 20 | 21 |

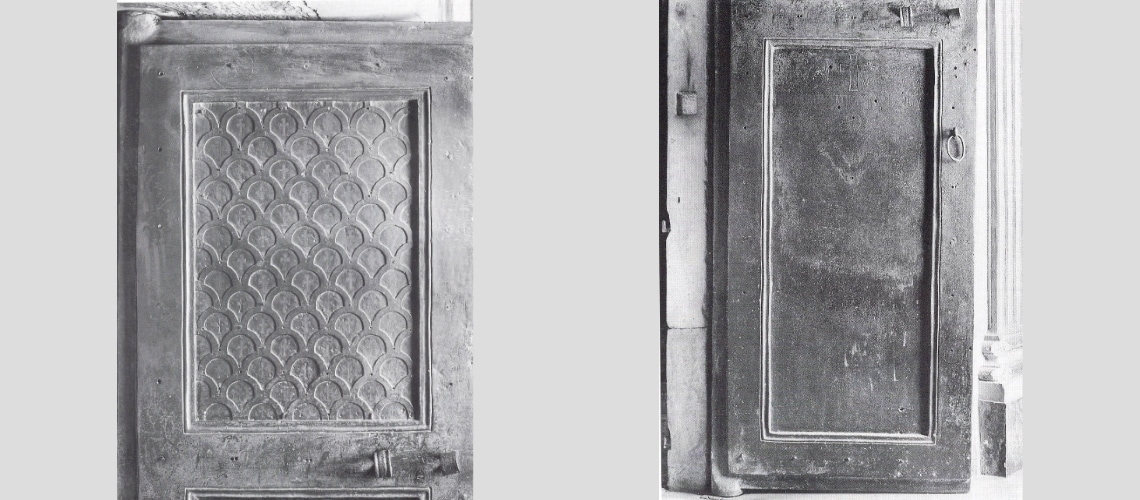

The door in Salerno Cathedral has eight inlaid panels, while the remaining panels feature the same type of chalices with crosses applied as the one in Atrani Cathedral. One of the inlaid panels bears the names of the donor and his wife: Landolfo and Guisana Butrumile; the door was made in Constantinople around 1085-1090. [Photos 22-26, bronze door of Salerno Cathedral and details of the door itself]

| 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 |

LE PORTE COSTANTINOPOLITANE A VENEZIA

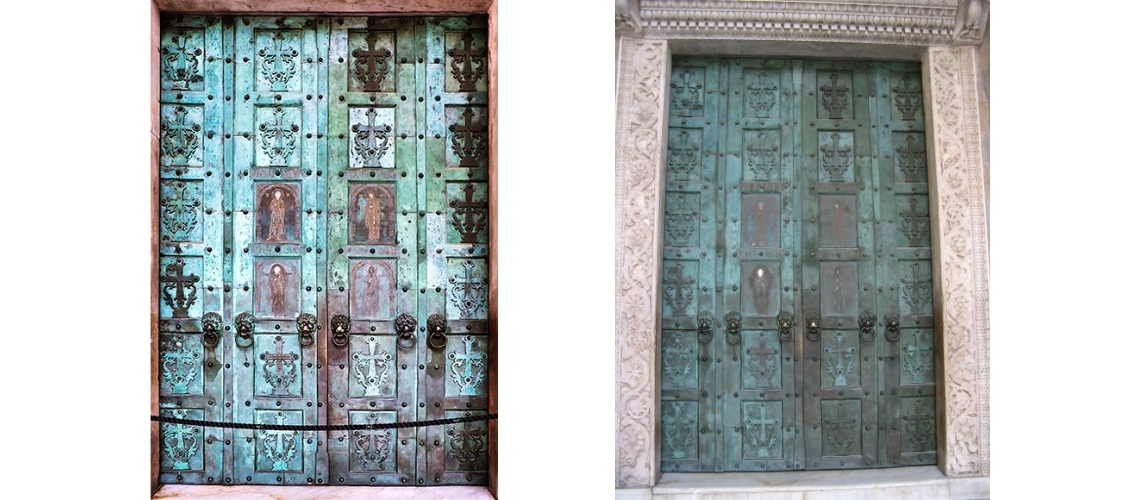

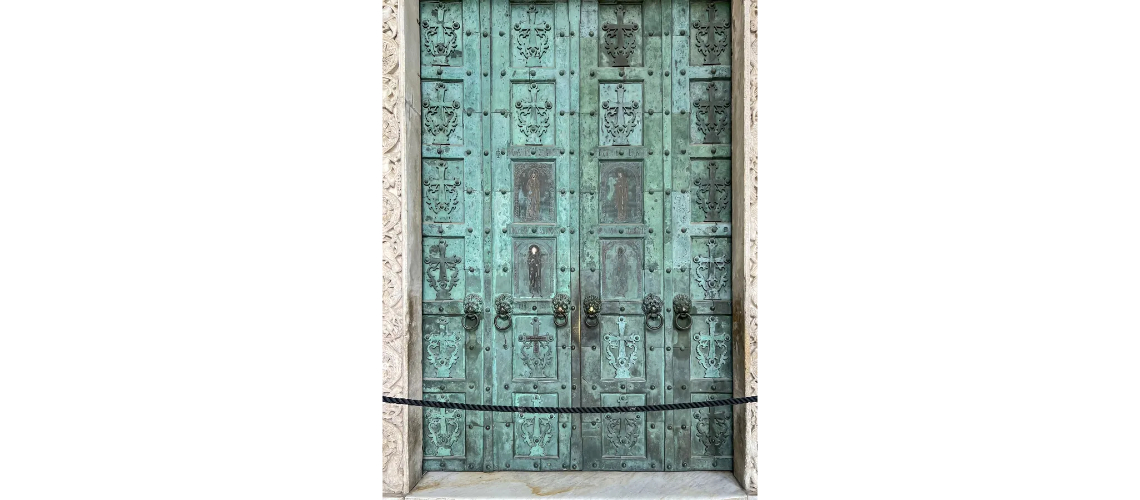

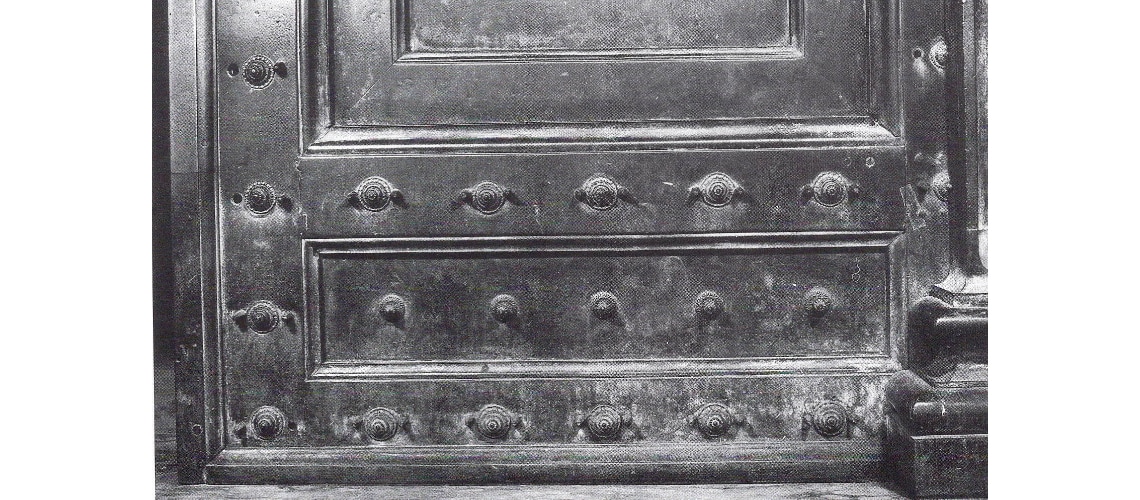

The two doors of St. Mark’s Cathedral in Venice, the central one in the atrium and the door of San Clemente, were made in Constantinople but are later than the previous ones, dating to the first half of the 12th century. Both are covered with bronze panels with typically Byzantine damascening.

The central door was commissioned and donated by the merchant Leo da Molino, procurator of the Basilica from 1112 until his death in 1146.

Both were conceived as the “Gates of Paradise,” featuring the supplication (Deesis) represented by Christ with the Virgin on his right and St. John the Baptist on his left, and the Litany of the Saints, for the remission of sins that would allow Leo da Molino and the faithful to enter Paradise. [PHOTO series VENICE, first the Maggiore and then San Clemente]

| 27 – Venezia, San Marco, Porta Maggiore | 28 – Venezia, San Marco, Porta Maggiore |

29 – Venezia, San Marco, Porta Maggiore, detail

30,31,32 – Venezia, San Marco, Porta di San Clemente and detail