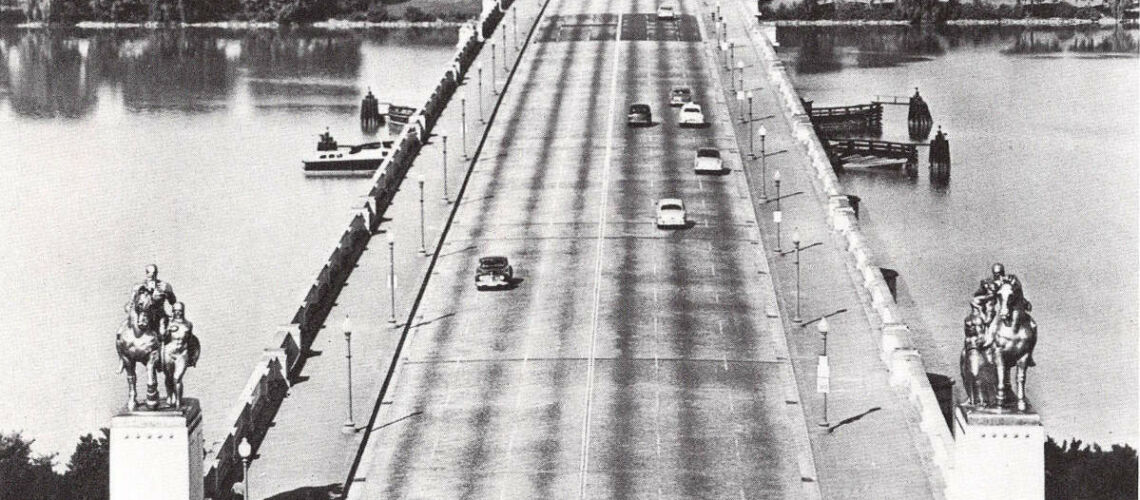

Arlington Memorial Bridge in Washington

In 1886 and then in 1898 the US Congress proposed for the first time the construction of a new bridge over the Potomac River in Washington, but to no avail. In 1902, the Senate Park Commission proposed in its so-called McMillan Plan to build one at the western end of West Potomac Park (an area that the Senate Park Commission successfully proposed as the site for the Lincoln Memorial) across the Potomac River to Arlington National Cemetery. . This bridge would line up with Arlington House as a symbol and memorial to the nation’s unification after the American Civil War.

On March 4, 1913, the US Congress finally enacted the Public Buildings Act, which, among other things, created and financed an Arlington Memorial Bridge Commission (AMBC) whose purpose was to design the bridge. The suggestion was for a classical style architecture on the type of bridges built during the Roman Empire, or a neoclassical model.

But due to the start of the First World War, the US Congress did not allocate the funds for the operation.

The US Congress finally authorized the construction of the Arlington Memorial Bridge in 1925.

With the project in hand, work began to authorize its construction: and in 1928 it was decided to place equestrian statues on the 4 pylons of the bridge project.

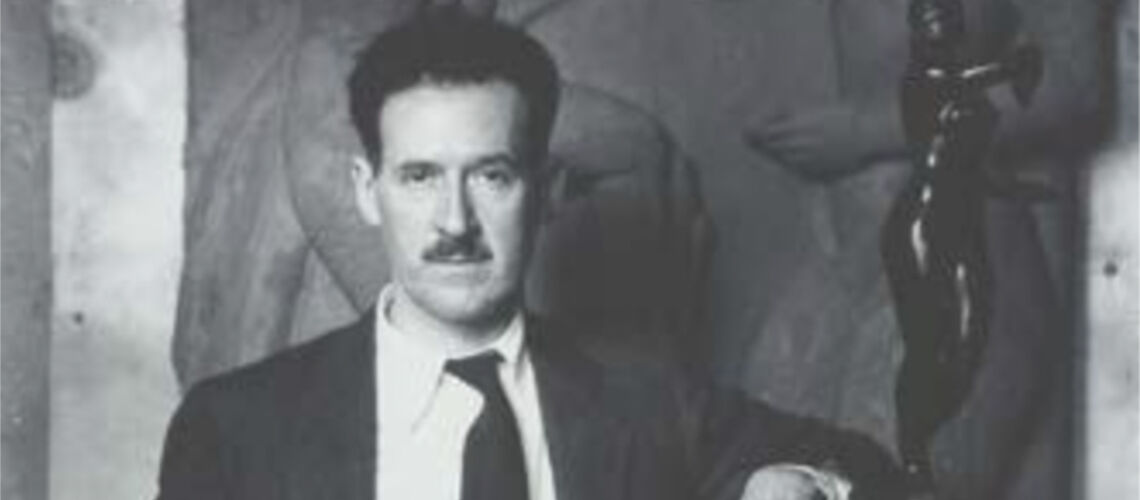

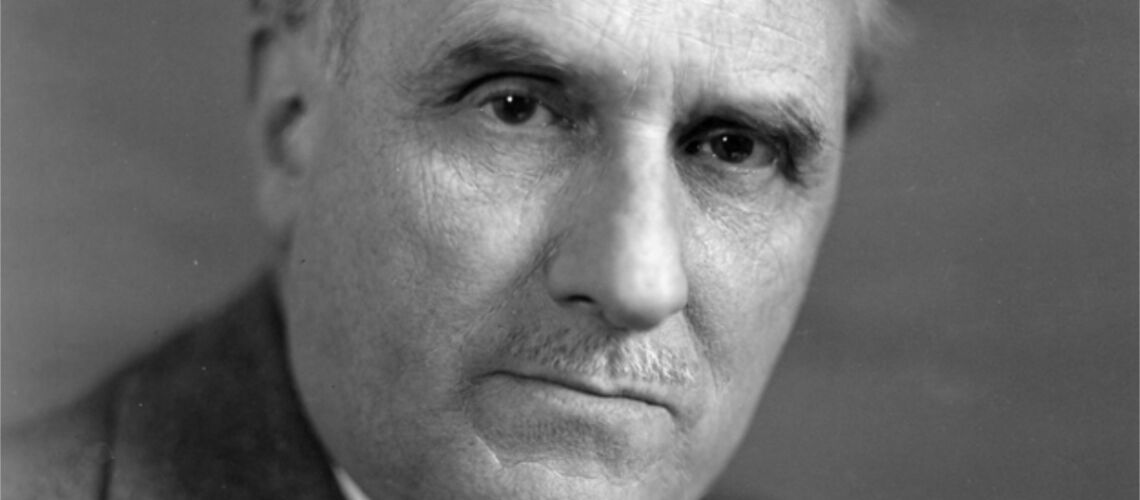

James Earle Fraser and Leo Friedlander were both commissioned to make the sculptures.

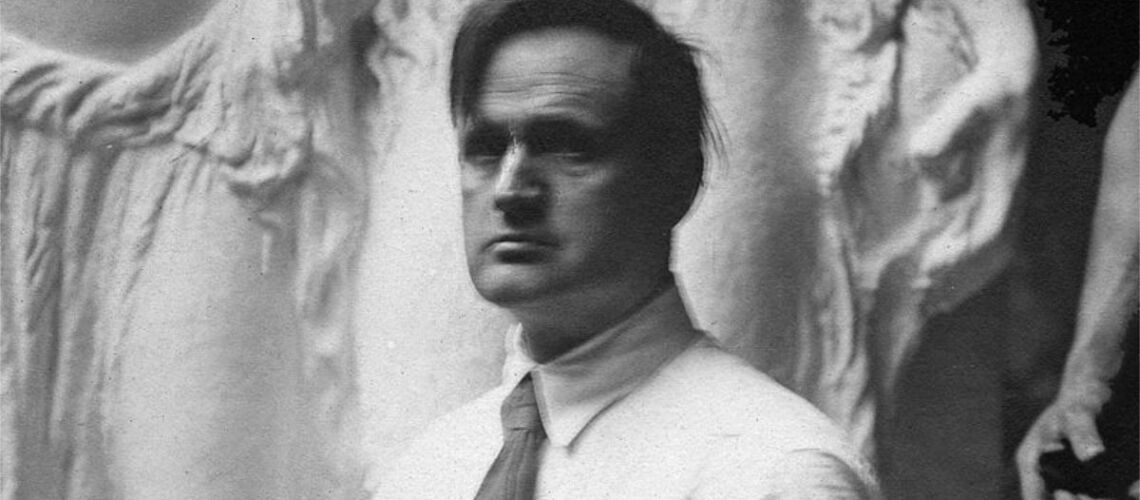

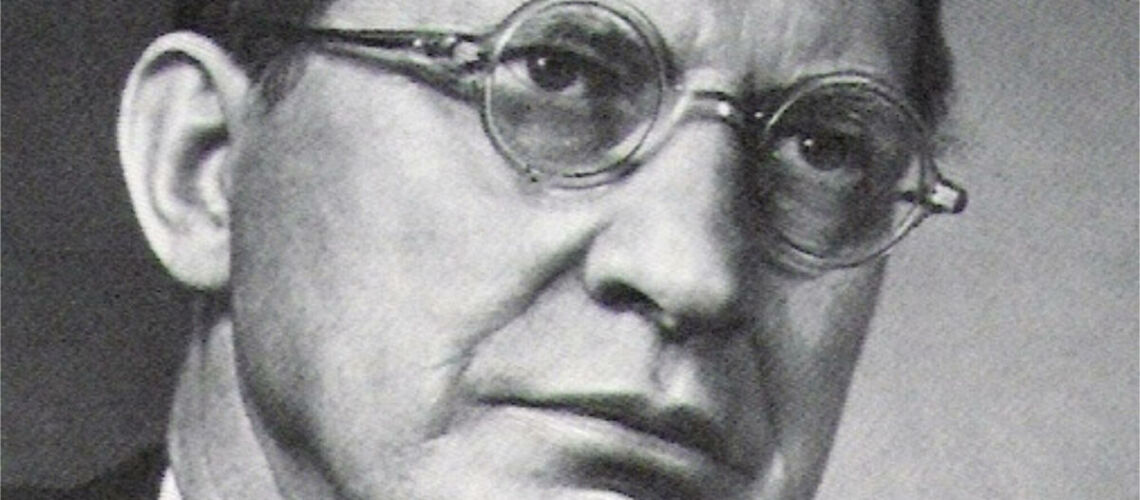

Leo Friedlander (July 6, 1888 – October 24, 1966), American sculptor, had studied at the Art Students League in New York City, at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Brussels and Paris and at the American Academy in Rome, he also had a passion for Etruscan art. He was assistant to sculptor Paul Manship and had taught at the American Academy in Rome and at New York University, where he headed the sculpture department. He was president of the National Sculpture Society. In 1936 he was elected associate member of the National Academy of Design and in 1949 he became a full academic.

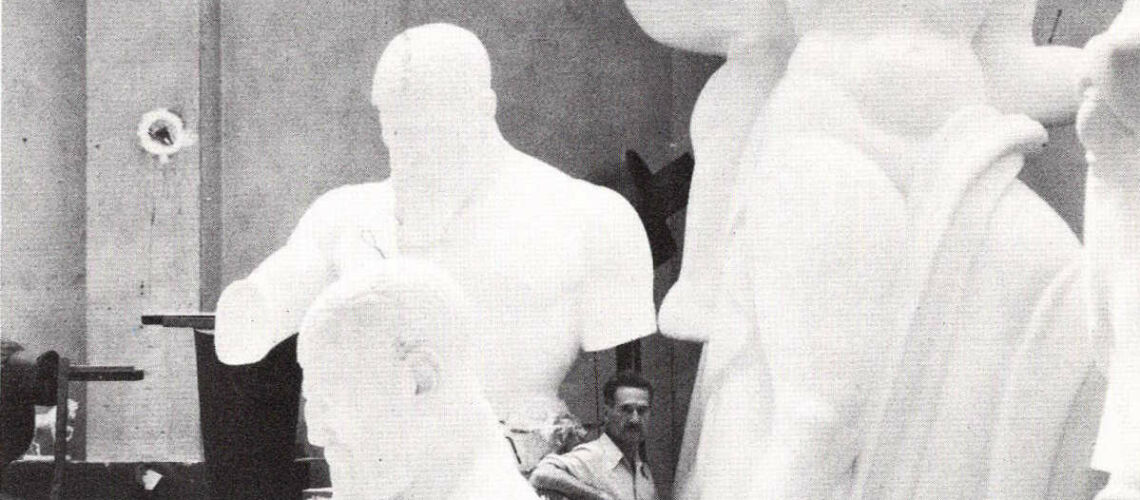

Government regulations required sculptors to create four versions of their plaster work before final approval for making could begin. These models had to be smaller and in three different sizes in addition to the actual size one. By June 1929, the smaller models were finished.

In the early 1930s, Friedlander and Fraser were discussing the positioning and pedestals for the two equestrian groups with the Army Corps of Engineers about .

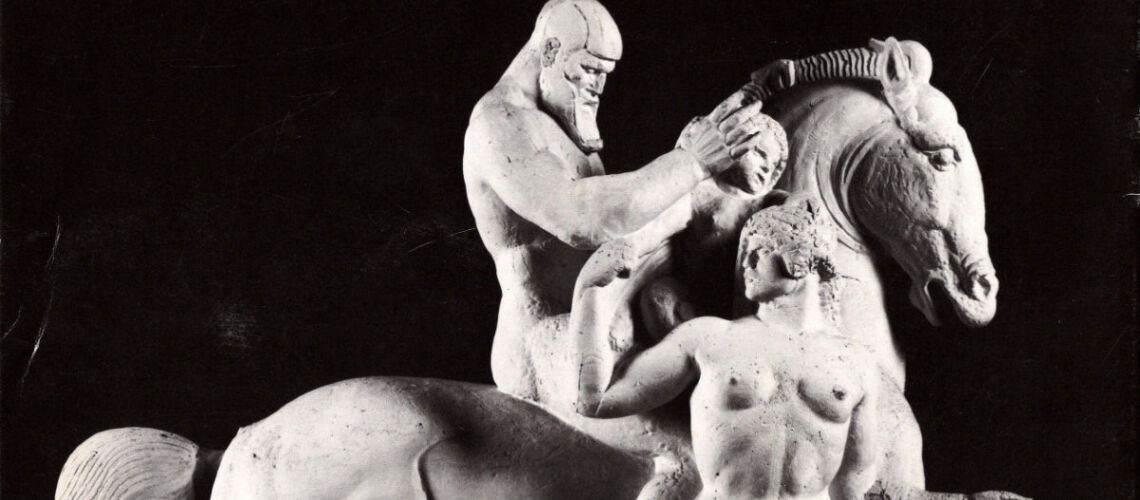

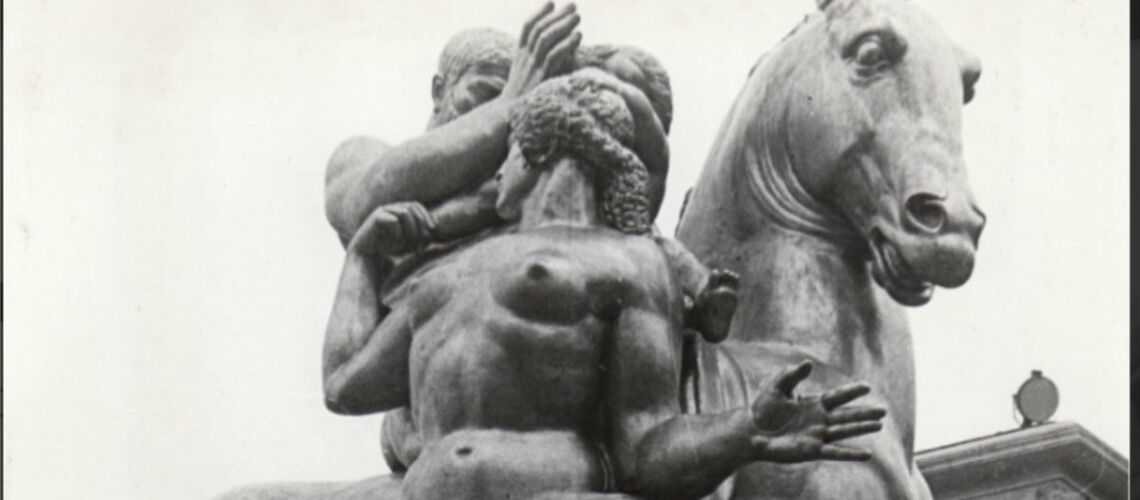

In December 1930 the Commission of Arts (CFA) approved the larger models in which the details on the sculptures were better read. Friedlander’s two statuary groups were called Valor and Call to Arms (later renamed Sacrifice). These two groups were to frame the entrance to the Arlington Memorial Bridge.

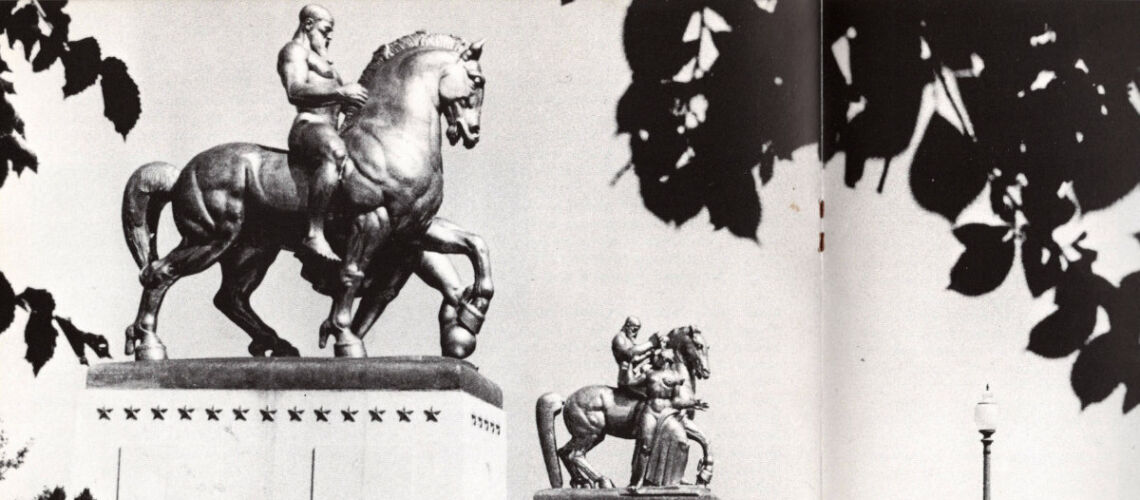

The set of 4 models by the two sculptors were called The Arts of War. Friedlander’s two statuary groups were in an Art Deco style known as “Delayed Deco”.

“Valor” was based on a study that Friedlander had completed in 1915-1916 while a member of the American Academy in Rome, while “Sacrifice” was created specifically for the bridge: the sculpture modeled in 1929, used the same figures as Valor but with the addition of the figure of a child.

The sculptures were originally to be made in bronze but the AMBC had specified instead that the statues were to be made of white granite.

Fraser’s two statuary groups were titled “Music and Harvest” and “Aspiration and Literature”. known as The Arts of Peace. Both modeled in a modern neoclassical style.

The contracts (probably for the full-size models) were made shortly after the CFA meeting on 11 December 1930.

In January 1931 the positioning of the 4 sculptures was again discussed.

Finally, on October 24, 1932, the Commission visited Fraser’s studio in Westport, Connecticut and approved his designs.

When the models half the size of the originals were about to be completed in 1933, the CFA put the project on hold. By now, the United States was in the midst of the Great Depression. The bridge was finished and cost more than budget and the funds available for the 4 granite statues were seized under the 1933 Economy Act. However, the CFA, with the full-size models already paid for, asked the sculptors to finish the their work. The CFA visited Friedlander’s studio in White Plains, New York, on October 14, 1933, and approved his designs.

In October 1933, the CFA approved the height of the statues (each would be 16 feet (4.9 m) high), the pedestals 13 feet (4.0 m) high, and the height of the plinth under the statues would be 1 foot tall (0.30m). Granite from Mount Airy, from North Carolina, would have been used for the bases.

Applications for partial funding for the four monuments in 1935, 1937, 1938 and 1939 were unsuccessful. However, in 1939 Fraser and Friedlander completed the full-size models.

James Earle Fraser suggested that the statues be cast in bronze, which allowed for considerable savings over granite sculpture; Friedlander and the CFA agreed with this suggestion, and in August 1941 both sculptors signed contracts to redesign their models for bronze casting.

But during the Second World War, the money for the project was no longer available.

In January 1948, the National Park Service informed the CFA that $ 1 million in authorized funds existed to complete the Arlington Memorial Bridge. Fraser reported on the foundry quotes he had received in the summer of 1947 and, at the request of the Park Service, the CFA asked Congress for an initial grant of $ 185,000 to start the work, but did not get it.

At the CFA meeting on September 13, 1948, the commission again discussed how to obtain an appropriation to perform the groups of statues. American foundries had not been converted from war work to art fusion. In addition, only one foundry in America was large enough to handle the work, and its contract required a sliding scale clause, a clause not accepted by federal budget officials. Congressmen thought of asking a European nation to consider statues, for the payment of castings, as part of the Marshall Plan, with broad consensus from the CFA and sculptors.

In 1949, the Italian government agreed to use funds from the Marshall Plan to cast the four statues of the Arlington Memorial Bridge. In October, officials of the National Park Service and the sculptors Fraser and Friedlander came to Italy to inspect various foundries and found a work agreement: and in 1950 the work began. The plaster models arrived in Italy in January. However, customs officials kept them for several weeks outdoors, in the cold, in the rain and snow. Fraser’s student, Edward Minazolli, traveled to Italy to help supervise the casting process and found that the models had deteriorated. With the permission of Fraser and Friedlander, he had them repaired and restored.

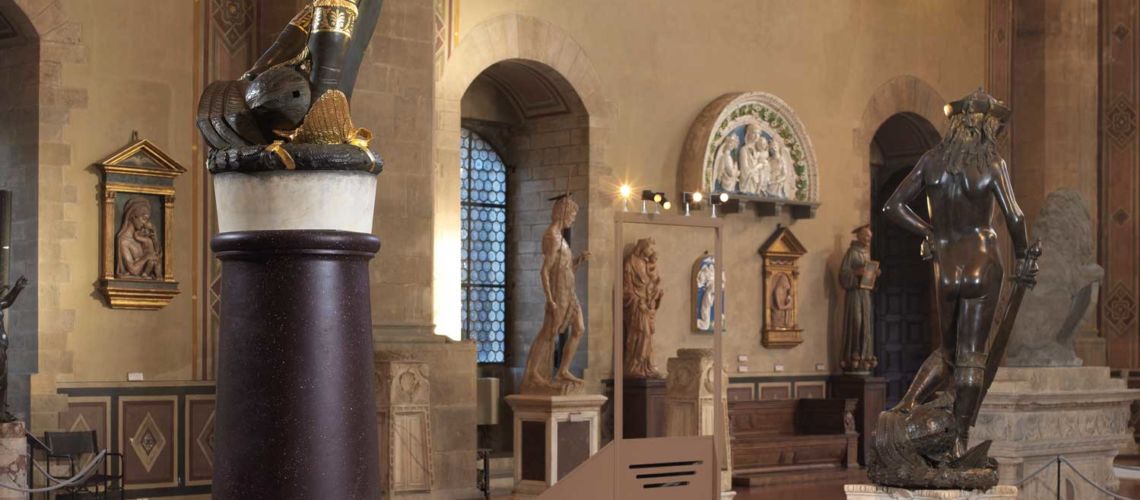

The Bruni Foundry in Rome and the Lagana Foundry in Naples cast the sculptures assigned to them. and intended to use fire gilding. But the quality of the samples was not satisfactory, as was the color of the gilding. Fraser then asked to apply for part of the casting work to the Battaglia foundry in Milan and the Ferdinando Marinelli Artistic Foundry in Florence. The work of the Milanese foundry was as discreet as that carried out by the Neapolitan foundry. The Florentine foundry, on the other hand, did an excellent job of casting but did not like the color of the gilding: it was then made in Milan.

The four statuary groups were assembled at the end of April 1951.

They were inaugurated on May 3 and then exhibited in various Italian fairs before being shipped to the United States. The four groups of statues were transported from Milan to Norfolk, Virginia aboard the SS Rice Victory, then placed aboard a United States Navy barge and taken up the Potomac River to Washington, DC.

During the inauguration of the four groups of statues on September 26, 1951, the Italian Prime Minister Alcide De Gasperi officially offered the statues to the United States as a gift from the Italian people, through the then Italian Ambassador Alberto Tarchiani, as a sign of gratitude for their assistance. American in the reconstruction of Italy after the Second World War; US President Harry S. Truman accepted the statues, inaugurated by the wives of James Earle Fraser and Leo Friedlander. In his remarks after the inauguration, President Truman pledged to remove some military and economic constraints imposed on Italy in the 1947 peace treaty.

Across from the Arlington Memorial Bridge from the District of Columbia, the Sacrifice sculpture is on the right.

A bearded and muscular male nude, a symbol of Mars, holds a small child in his arms, with his head bowed. The half-naked woman is to her right, from behind with her head turned back to look at the knight, while with her outstretched right arm she touches his right elbow.

Each monument weighed approximately 80,000 pounds (36,000 kg). Each was 19 feet (5.8 m) tall, 16 feet (4.9 m) long and 8 feet (2.4 m) wide. While the pieces of the Sacrifice were all welded together, those of James Earle Fraser’s “Music and Harvest” were bolted together cold.

The total cost of transporting, casting, and gilding the four groups was $ 300,000. Fraser and Friedlander were each paid $ 107,000.

Each pedestal has 36 equally spaced gilt bronze stars at the top, representing the number of states in the United States at the time of the American Civil War. At the front of each pedestal is a classic flower crown, designed and sculpted by Vincent Tonelli (who also sculpted the Trylon of Freedom in front of E. Barrett Prettyman’s US courthouse). According to art curator Susan Menconi The Arts of War and The Arts of Peace were the largest equestrian sculptures in the United States.