Sergio Benvenuti, an artistic friendship and a long American history - The Broncos

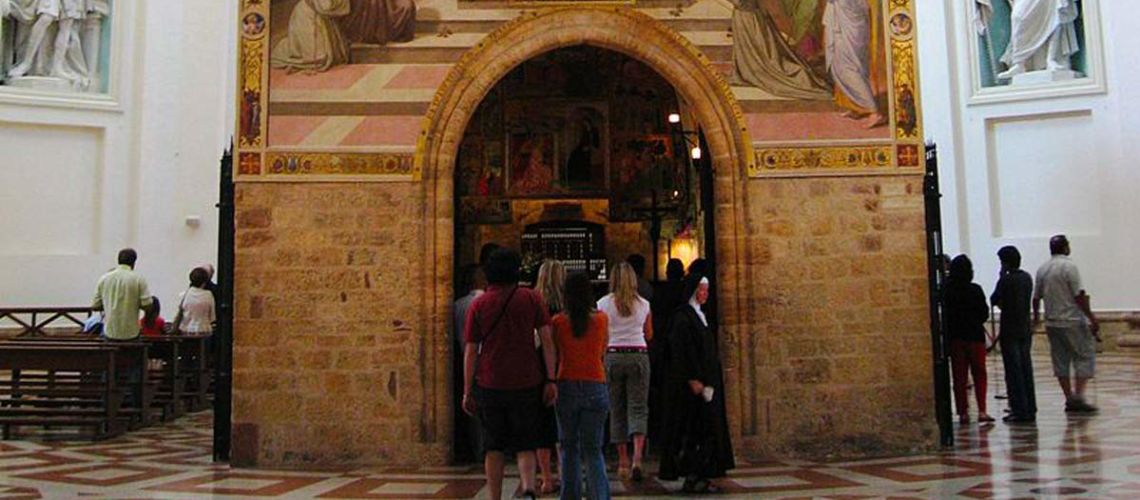

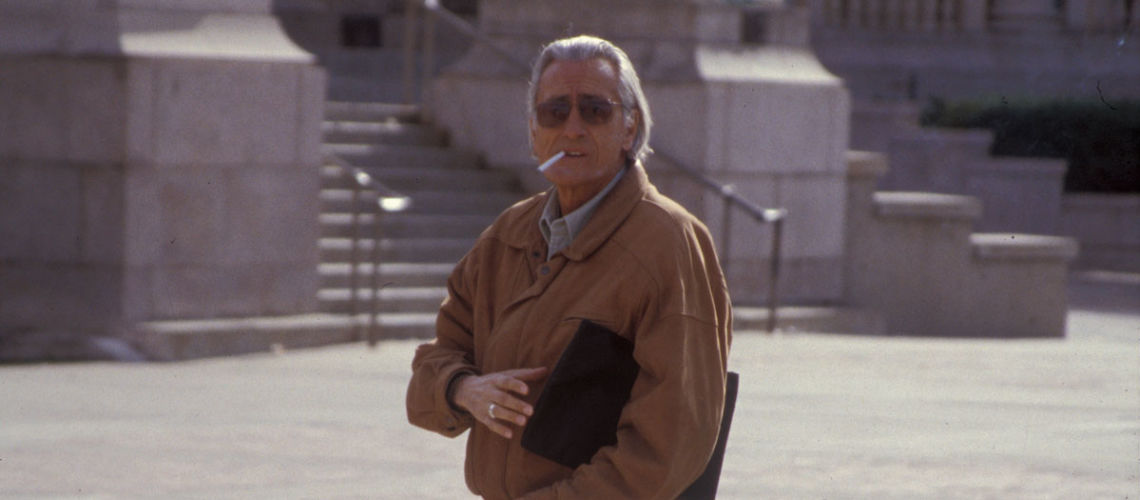

After the inauguration of the Fountain of the Two Oceans in Saint Diego, the contacts between Dudi and Pat Bowlen with me and Benvenuti softened, each one taken from their work; they confined themselves to greetings for the year-end holidays.

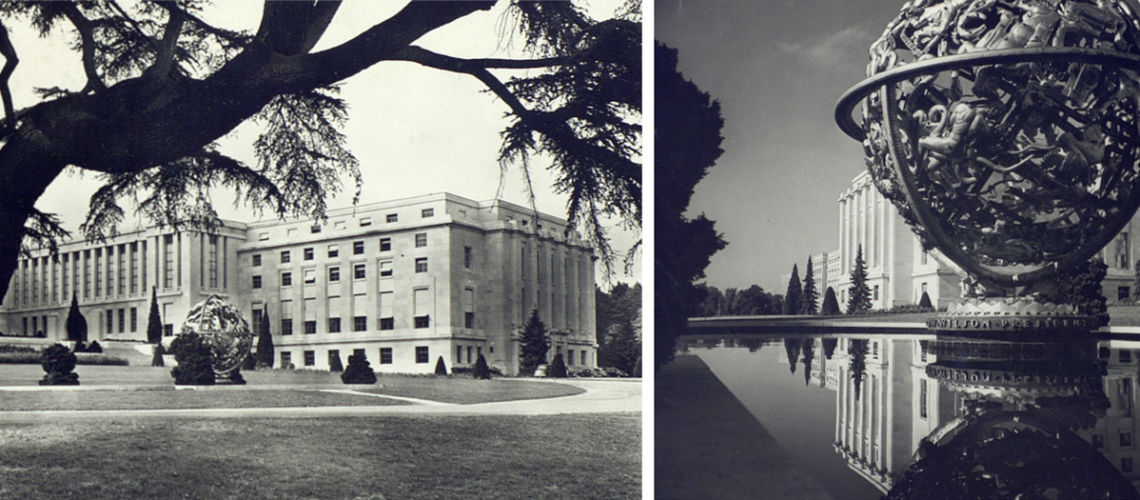

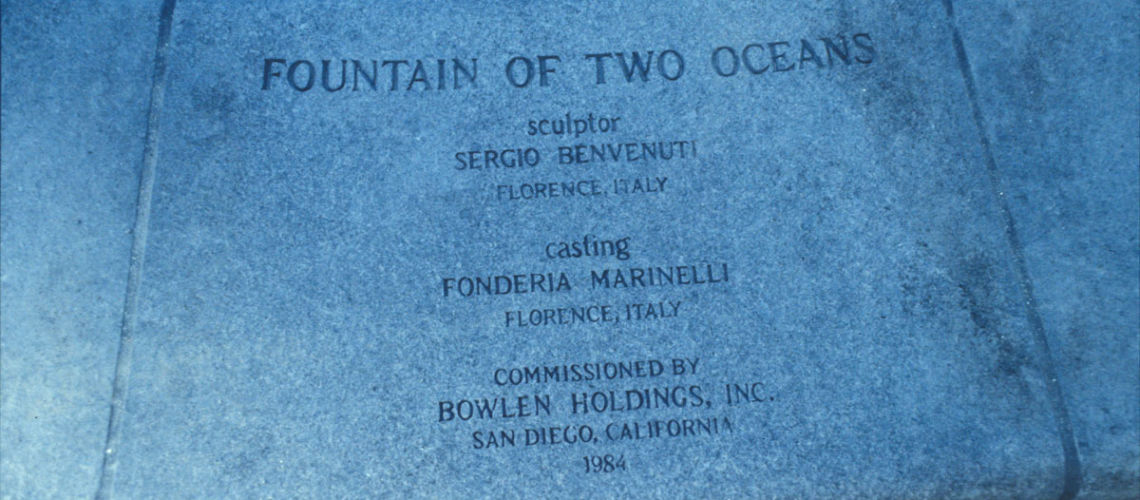

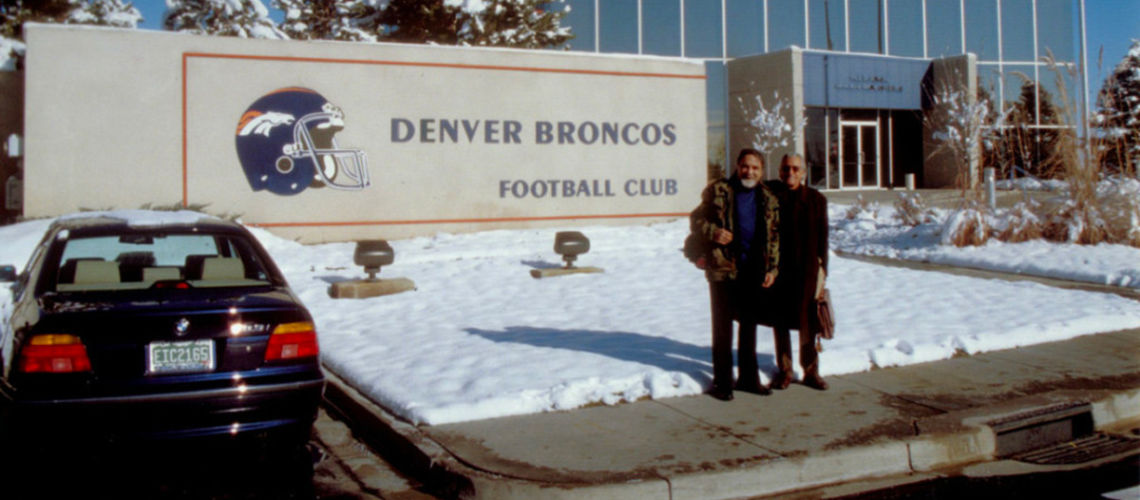

Much later, one afternoon Franco Barducci, director of the Galleria Bazzanti, received a phone call: it was Dudi Berretti who was looking for Ferdinando Marinelli. As if by magic the past years disappeared, the voices on the phone consolidated the old friendship in an instant. Once again Dudi Berretti, commissioned by Pat Bowlen to take an interest in the creation of a great monument for the construction of a new football stadium in Denver for the Broncos team, of which Bowlen was president,

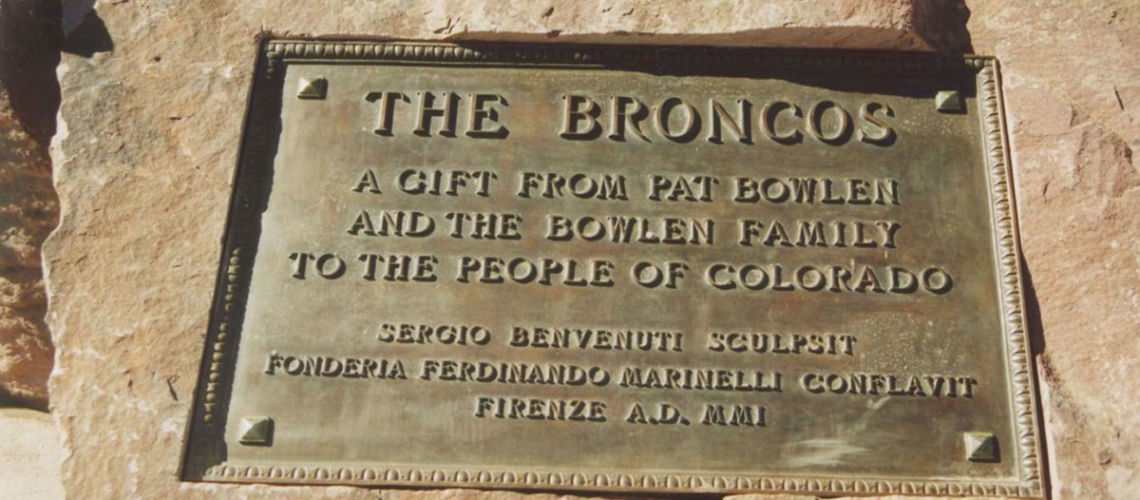

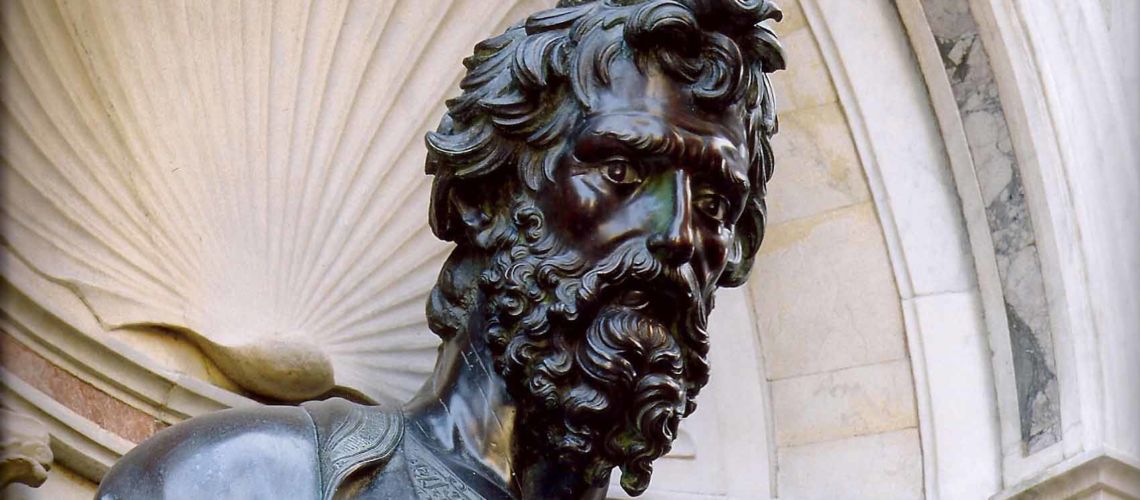

he turned to the binomial Ferdinando Marinelli-Sergio Benvenuti. The calls between the three of us followed each other along with the faxes, exchanges of drawings, sketches, notes. The new stadium projects included around it an embankment that Dudi wanted covered with grass, shrubs, trees, with various grazing bronze horses. It was then that Pat Bowlen decided to give the citizens of Denver a monument with a strong symbolic content: a group of seven horses that climbed the embankment near the entrance stairway of the new stadium. The horses had to be seven because this was the number of the champion of the Broncos team, John Elway, (and also the lucky number in the life of Dudi Berretti).

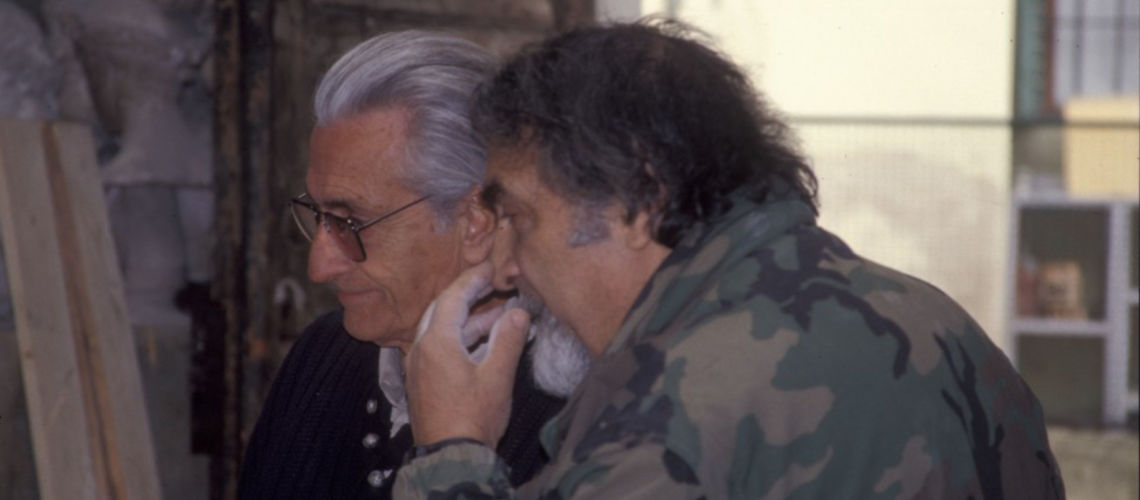

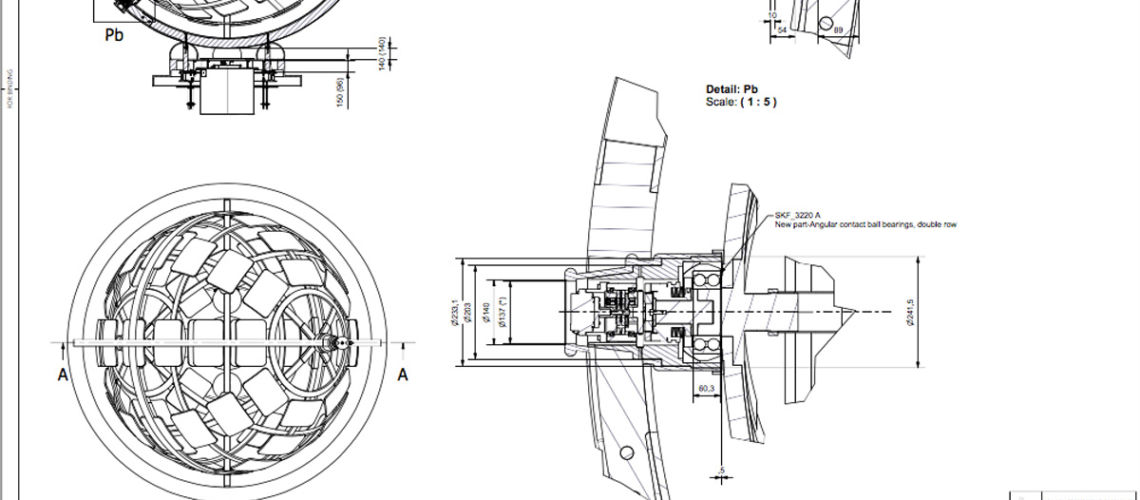

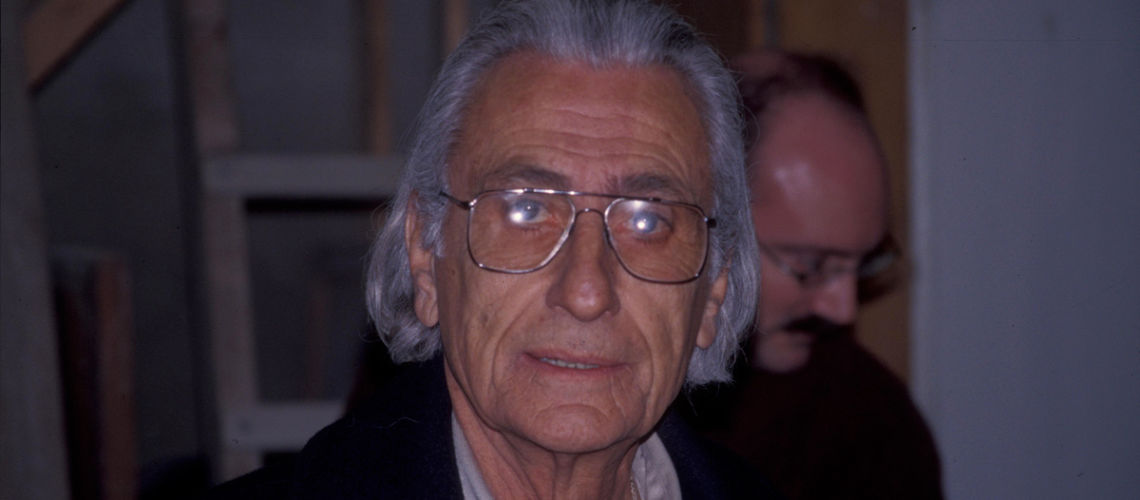

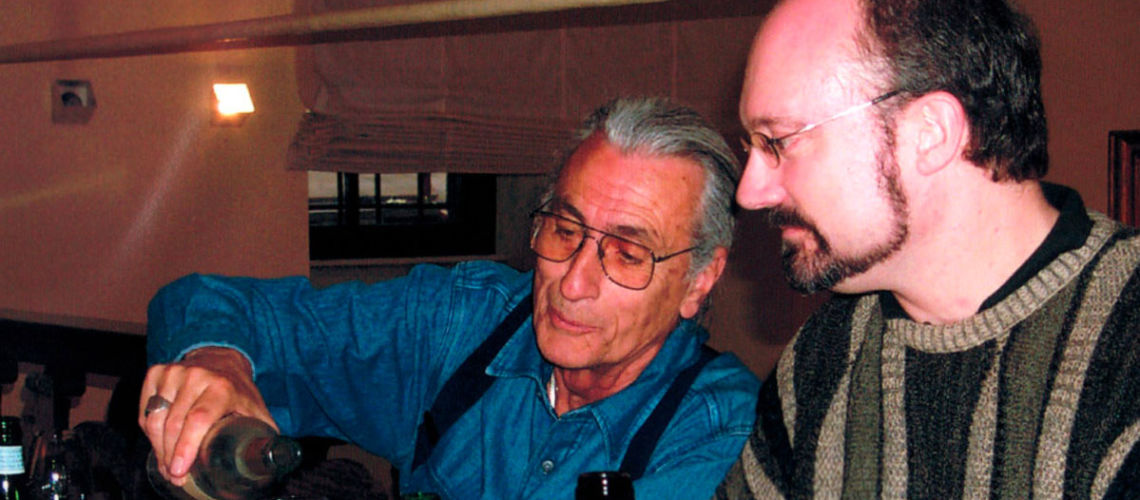

At the invitation of the “Stadium Management Co. Denver Broncos” I flew with Sergio Benvenuti to Denver to present the project to Stadium Management and the various artistic commissions in the District. The monument received the full approval and applause of all. Upon returning to Florence Benvenuti immediately set to work performing the models ad 1/5 of the size of the final sculpture. Shortly afterwards Dudi Beretti together with the landscape architect Lanson Nichols came to Florence to see the models and to discuss with us the best setting for the fund on which the seven horses would be run.

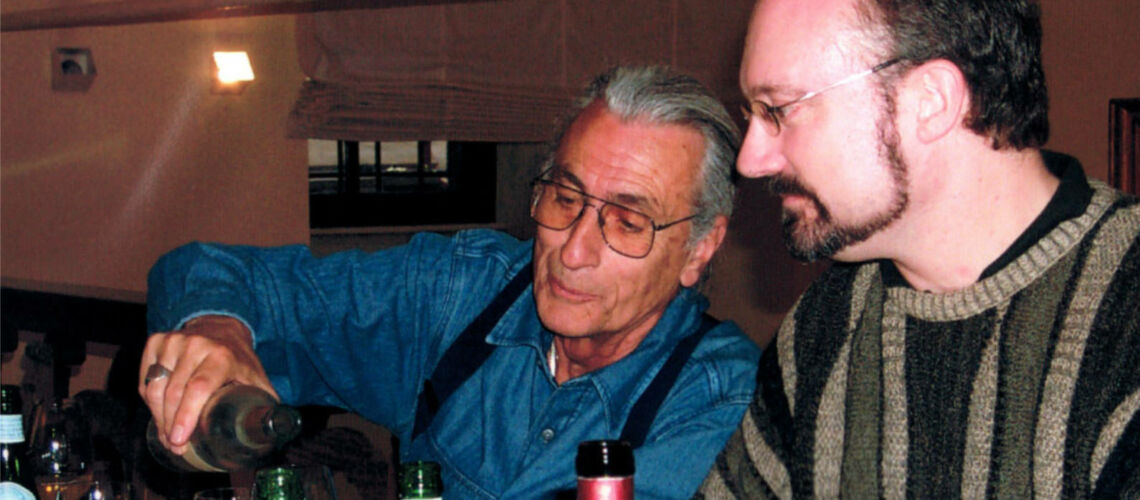

At the table, as we know, we discussed better.

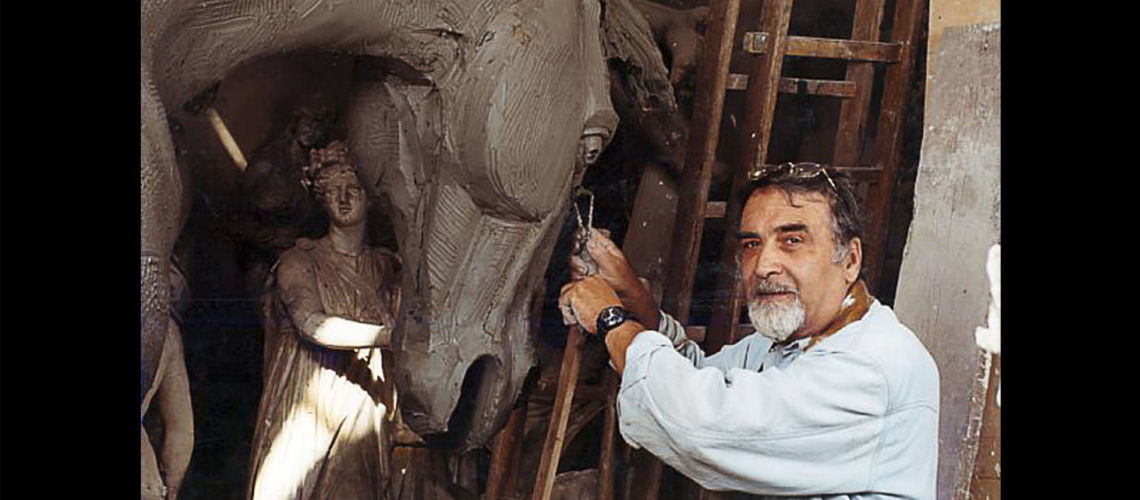

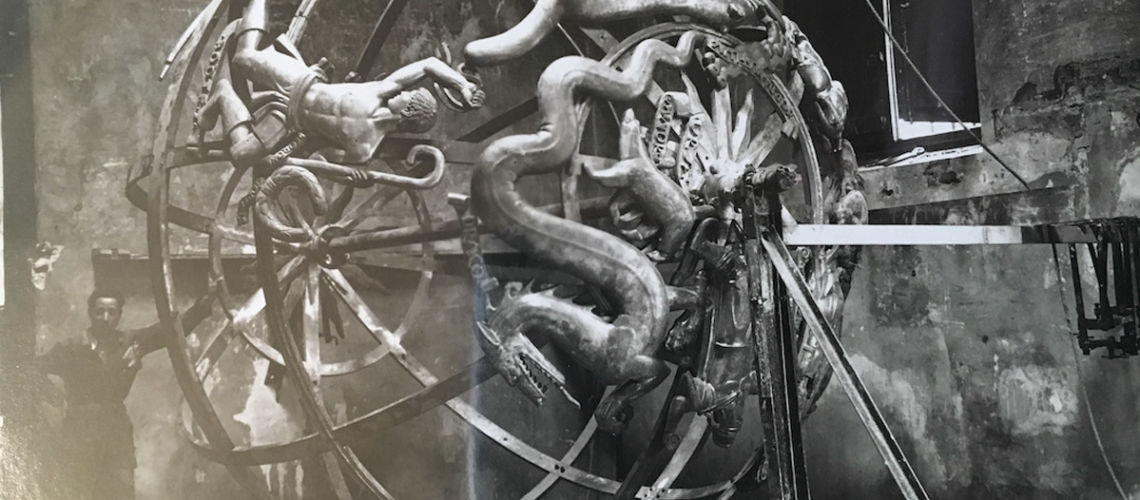

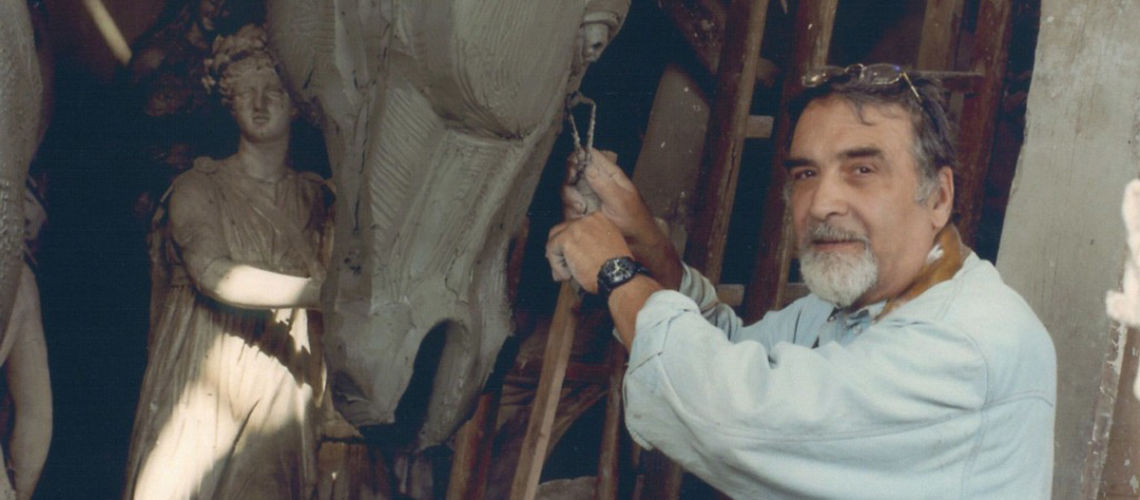

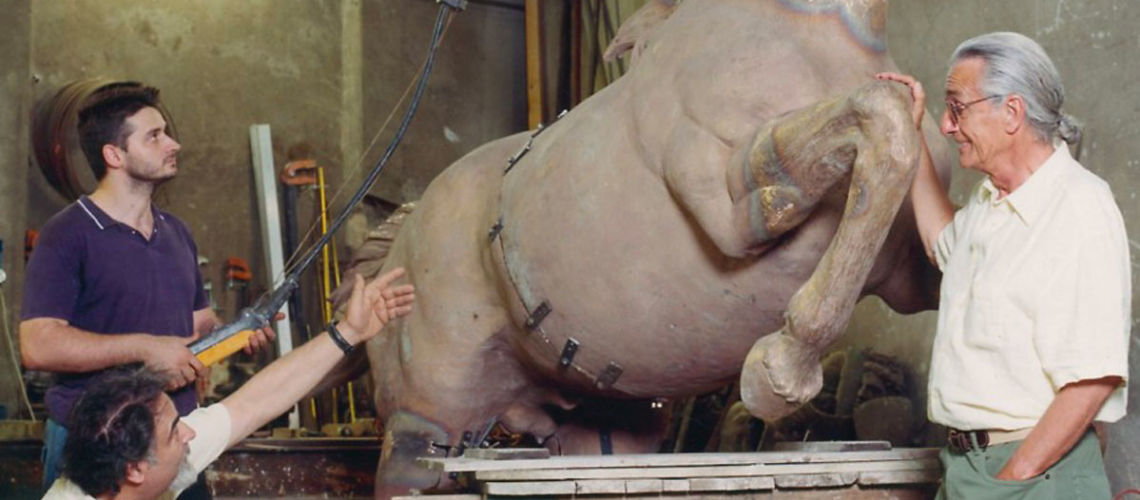

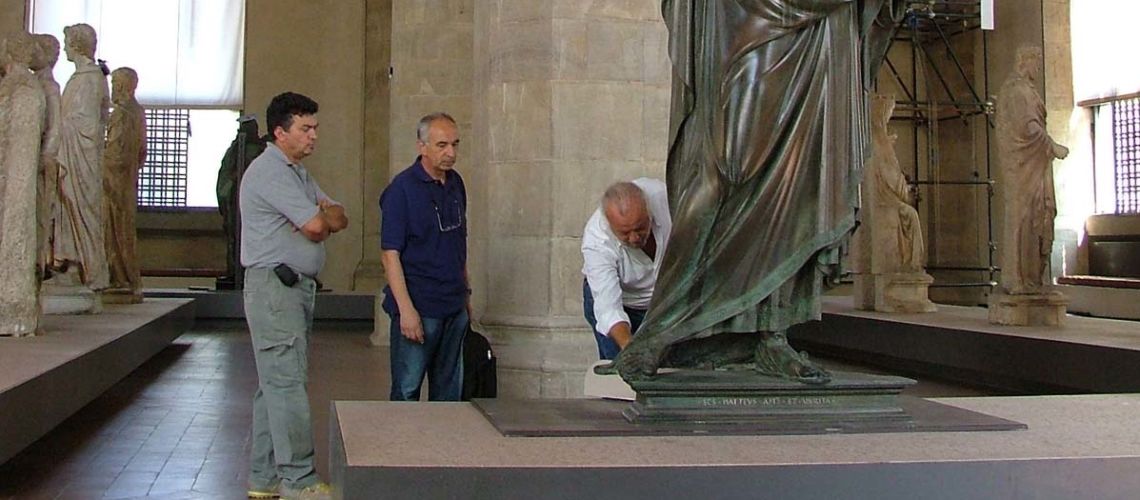

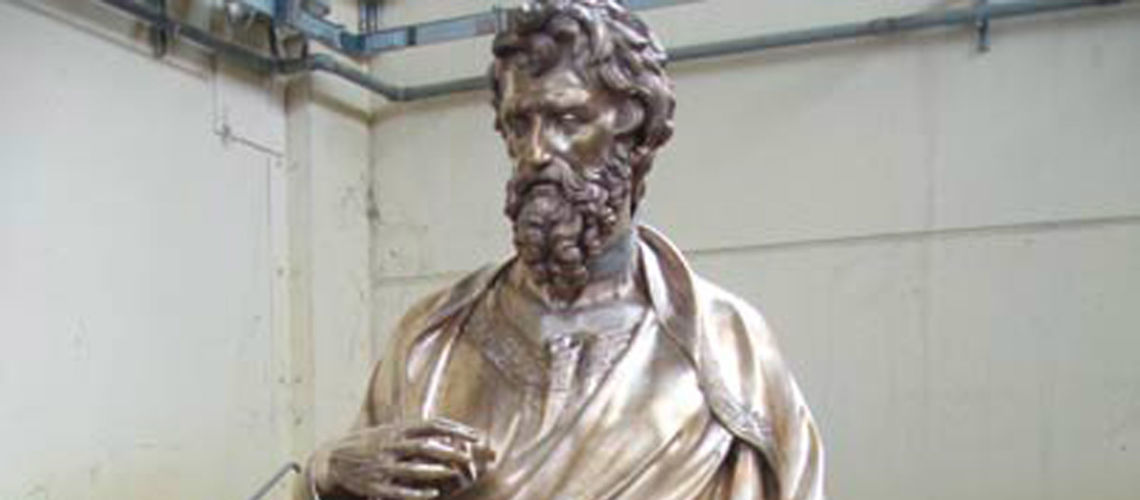

At the Marinelli Foundry, Benvenuti began enlarging the first horse, then continuing with the other six.

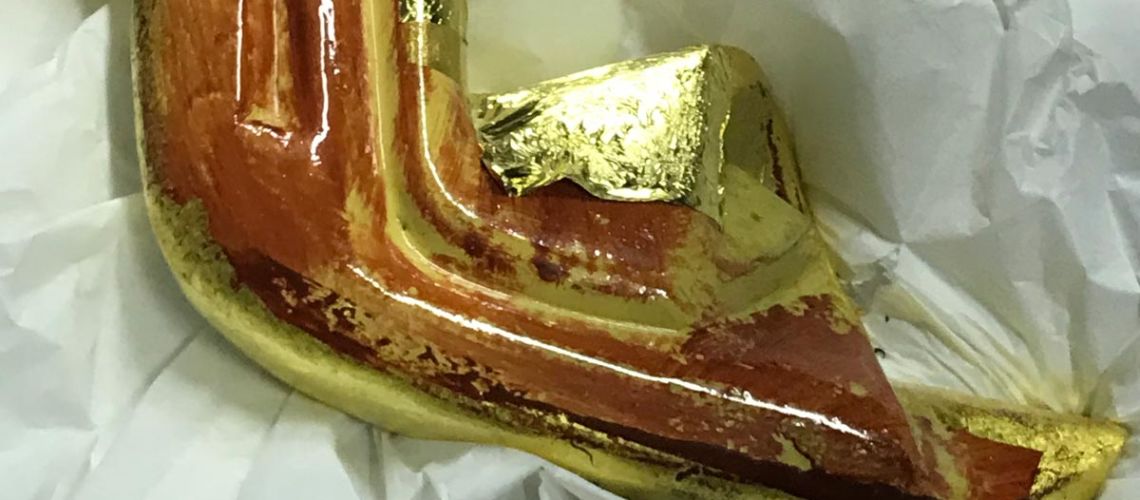

As soon as a horse was brought to the required size, the negative mold was made in the foundry and then the wax that was immediately retouched and then taken to the subsequent phases necessary for the bronze casting.

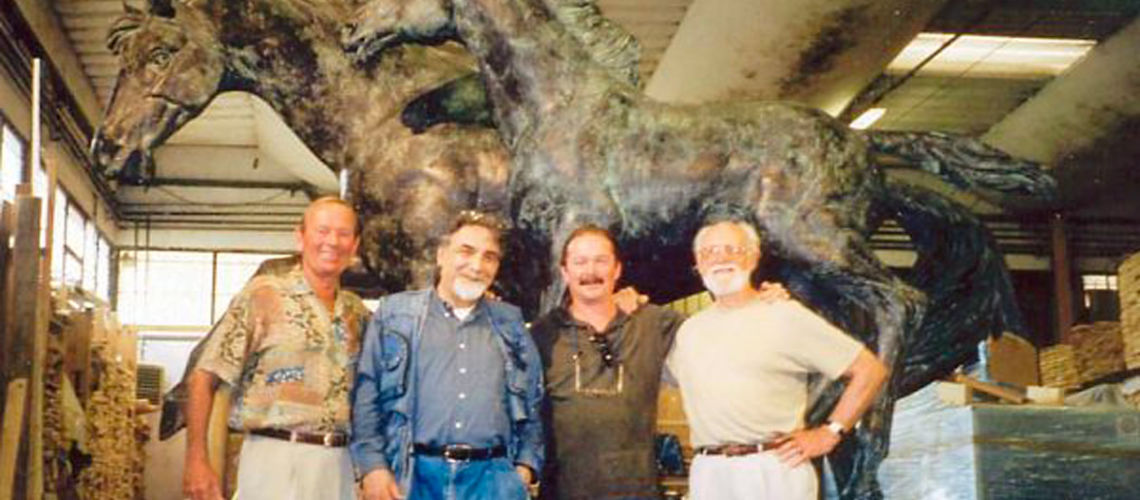

A few months later Dudi Berretti accompanied appointees from the Studium Management Co. Denver Broncos, who at the Foundry checked with satisfaction the progress of the work.

They were also introduced to the specialties of Tuscan cuisine.

Castings proceeded,

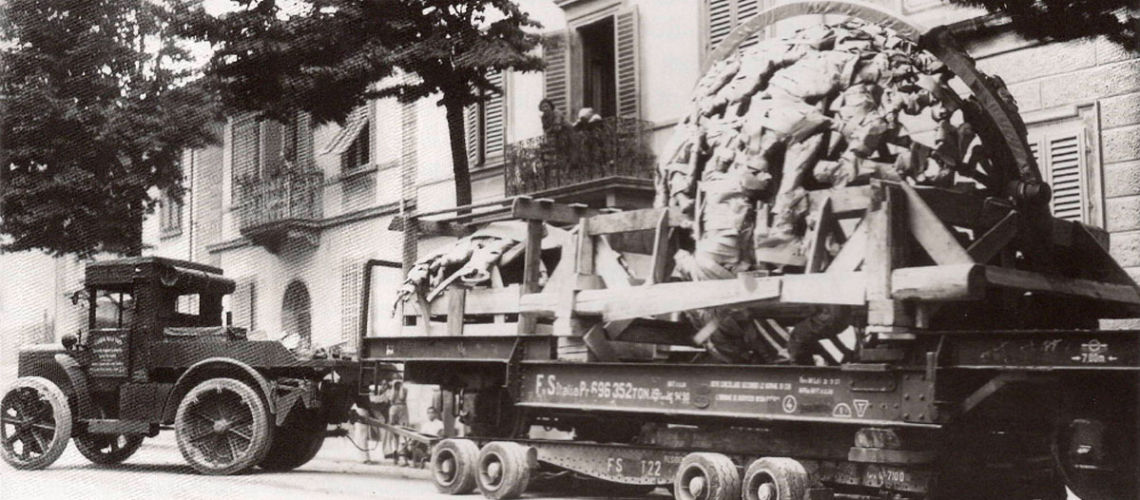

and while the first four bronze horses were on the ship bound for the port of Huston and from there to Denver, Pat Bowlen himself came to Florence to meet Sergio Benvenuti and to view the last three horses, which impressed him very much. After drinking special wine we had his approval.

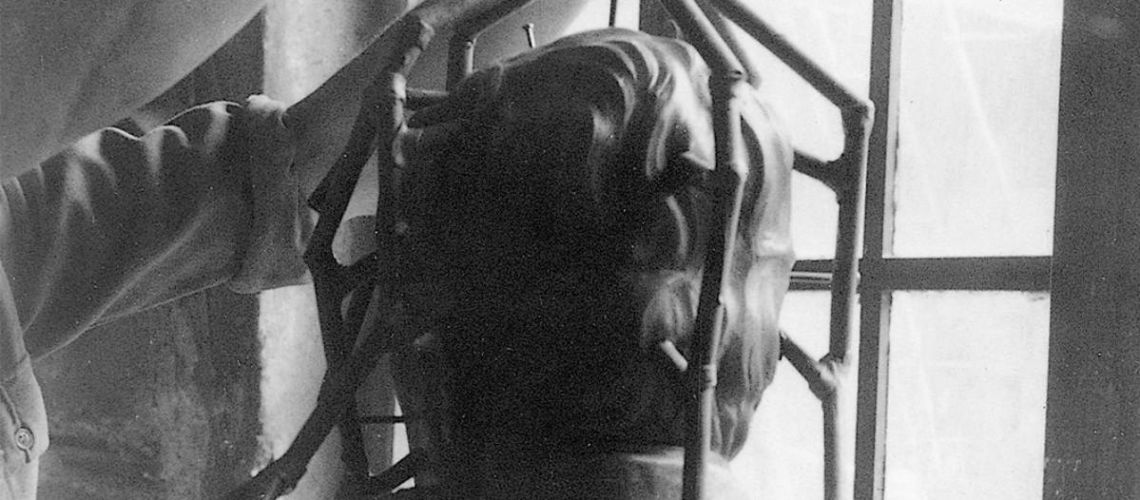

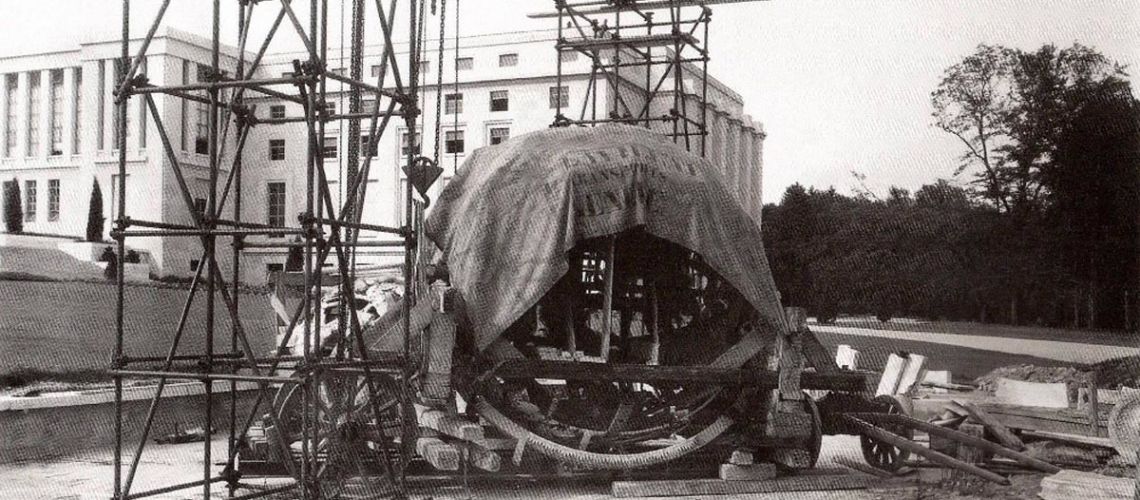

The seven horses were already in Denver when together with Benvenuti we also arrived in Denver to direct the assembly of the great fountain.

Placing and assembly work lasted a few days,

until the official inauguration.

It has been a wonderful experience.