Michelangelo and the marble quarries

Part II

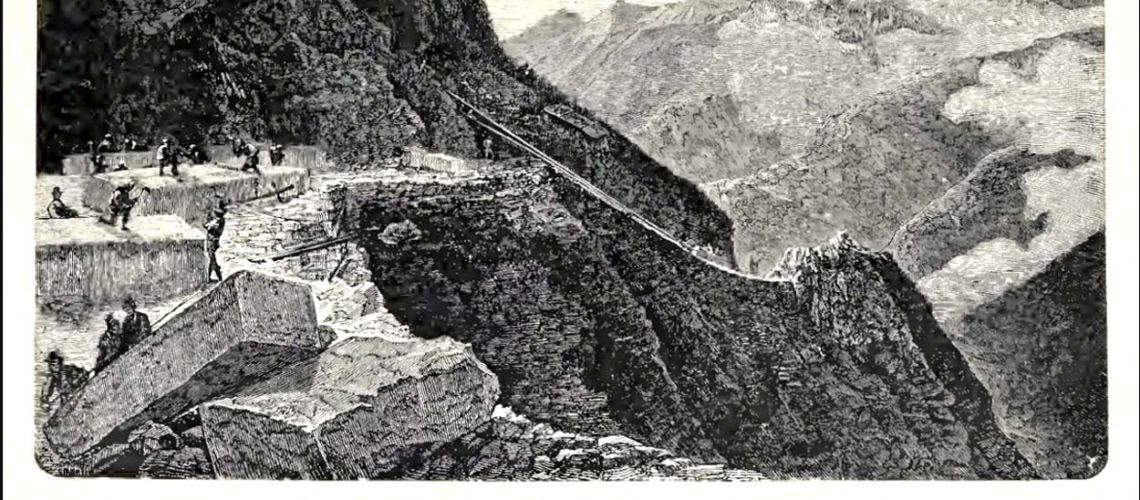

The quarries of Serravezza - Pietrasanta

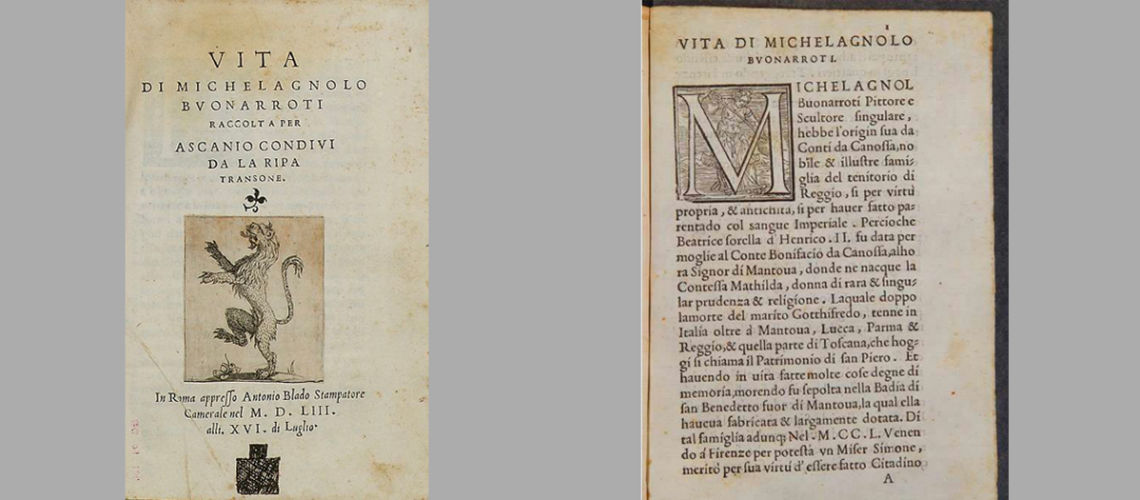

Michelangelo, as he himself wrote in March 1520, at the request of the pope, in 1517-8 left from Rome for the Serravezza quarries: “I was sent from Rome to Seraveza, before I started to quarry, to see if there was marble”.

But he goes on to get them from the Carrara quarries .

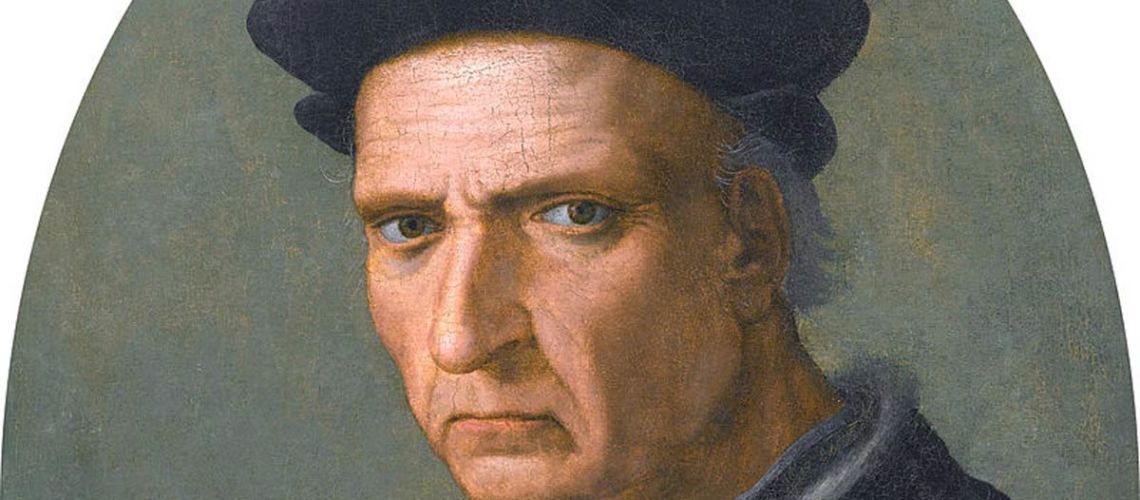

Finally, however, he persuades himself to have the marble extracted in Serravezza as the Pope asked him, with the appreciation of Cardinal Giulio dei Medici, a family who owns the quarries of Pietrasanta and Serravezza, who wrote to him in this regard on 23 March 1518. Cosimo I dei Medici will then build the Medici villa of Serravezza in these lands in 1564, probably by Buontalenti architect .

From a letter also written in March 1920 to Sebastiano del Piombo, Michelangelo, who has always been against the quarries of Searravezza, justifies this change by saying that he was no more satrisfied by the Carrara’s quarrie workes. So I went to get these marbles to be quarried in Seravezza owned by Florentine people.

And it certainly weighs on him having to open new virgin quarries, rather than using those very well-known of Carrara. Furthermore, the Carraresi boycotted the transport by sea of the blocks already purchased and quarried, so much so that Michelangelo was forced to resort to the recommendation of Jacopo Salviati to convince a ferryman from Pisa.

But Serravezza disappointed him: the marbles were not as he would had liked them, deliveries were very late, the road to reach them was not yet finished. Now Michelangelo was very angry, and on April 18, 1518 he wrote from Pietrasanta to his brother Buonarroto that he was desperate and that he would had ride on horseback and go to visit the Cardinal de ‘Medici and Pope telling them that he would leave return to Carrara, were the quarry workers where praying him to go back.

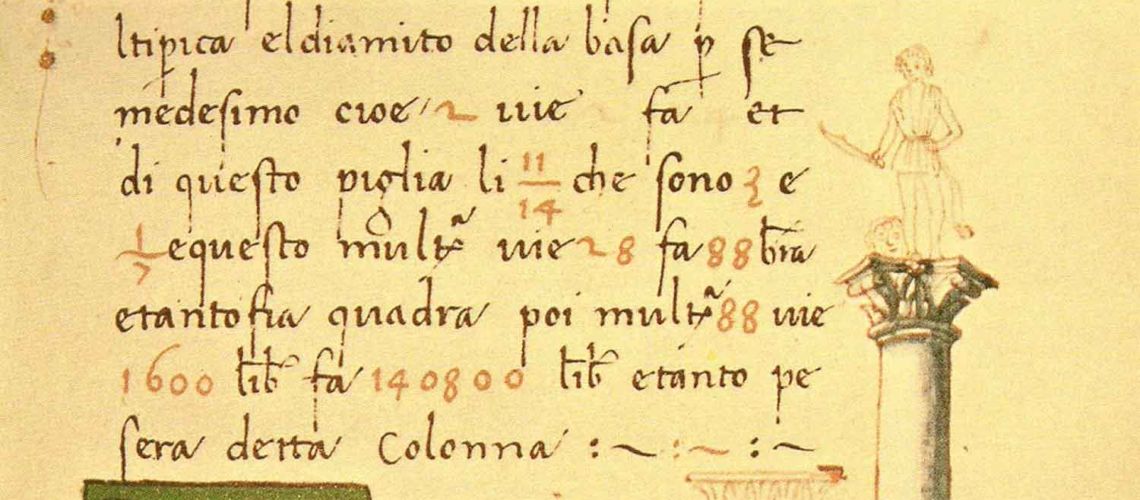

He actually returns to Carrara, but things have become enormously complicated there too: always higher prices for marble and infinite difficulties for transport. In Serravezza things where no better: the stonemasons, all from Settignano near Fiesole, had no experience in quarrying marble, they had continuously accidents in the quarry, one of which had been fatal, it was not possible to dig a healthy column without unexpected veins or without breaking it. He had to commission and pay some architectural pieces three times, he had to personally go and teach the inexperienced quarrymen the quality of the marble, as he wrote in the letter to Domenico di Boninsegni at the end of December 1518.

After a series of accidents also in the loading on ships, misunderstandings with the Marquis Alberico Malaspina,

Michelangelo commissioned blocks from the Carrara quarry workers, and communicated to Cardinal Giulio dei Medici that he had found these quarrymen more humble than they usually did. The pope temporarily renounced the plan to exploit the Serravezza quarries and accepted Carrara, as Michelangelo wished. Vasari, an artist at the service of the Medici, in his Dell ‘Architettura will be the only one who will praise the marbles of the Pietrasanta quarries, owned by the Medici.

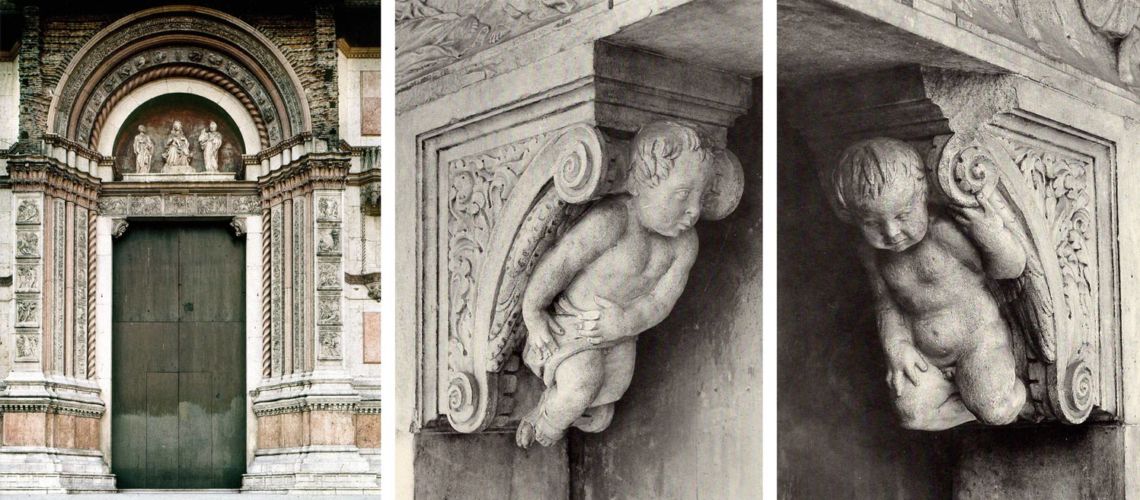

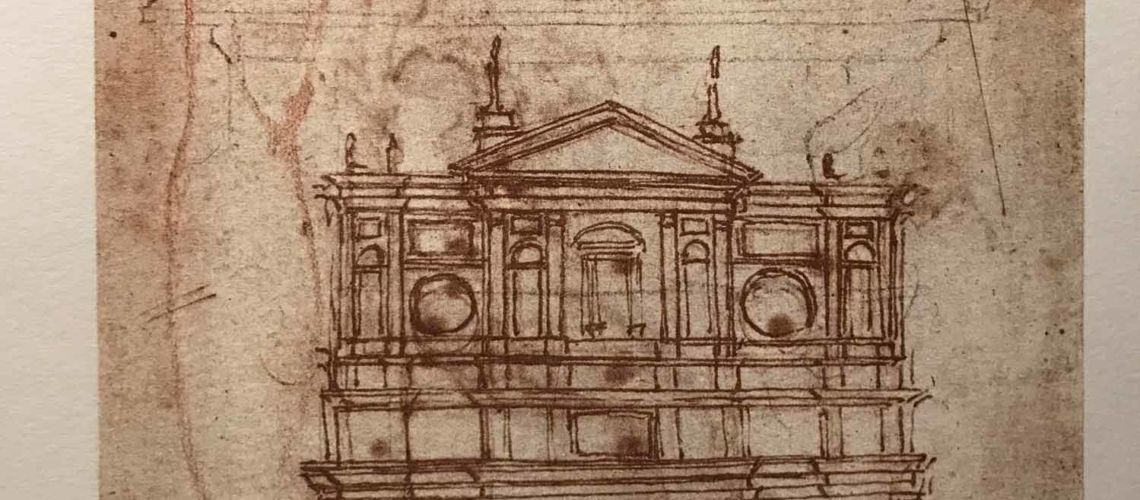

Things continued to go slowly and Cardinal Giulio Della Rovere sended the papal secretary Pallavicino to Michelangelo’s studio in Florence, where he finded with satisfaction 4 statues sketched for the facade of San Lorenzo.

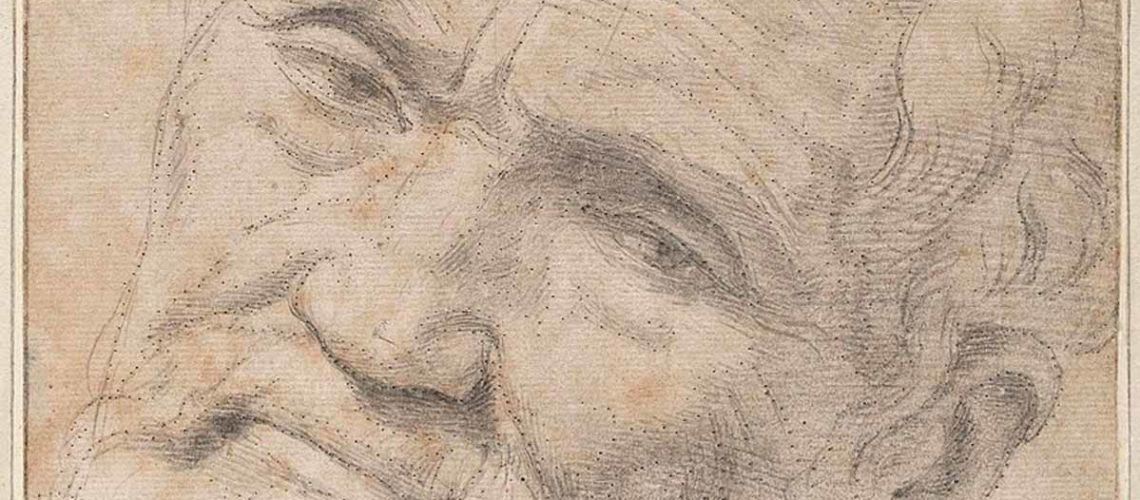

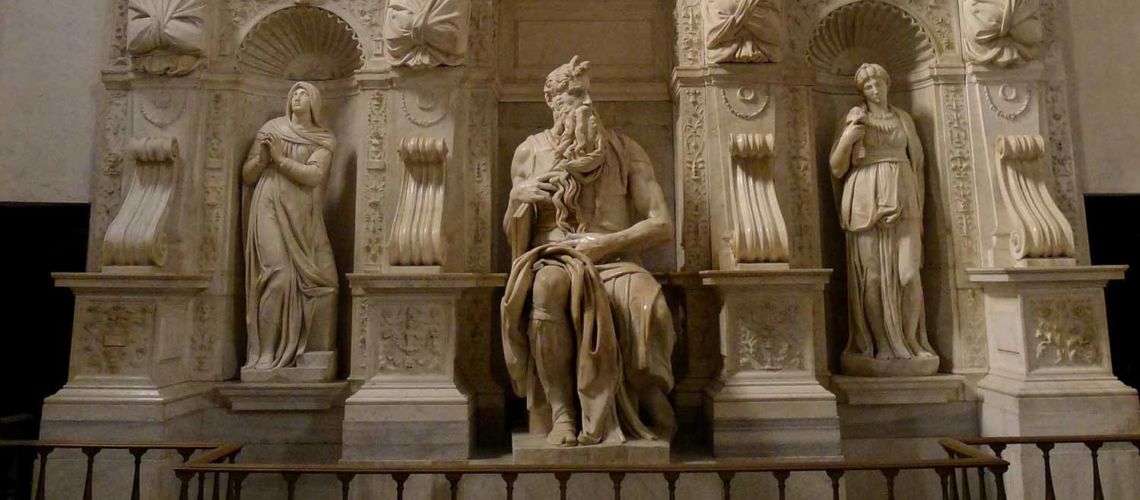

To check the supplies constantly delayed of the marble for the facade of San Lorenzo Michelangelo sended his disciple Pietro Urbano on horseback several times to the Carrara quarries together with an apprentice. Difficult task, because being able to identify microfractures in the blocks and even more to understand which direction they take within the block, was very difficult. So much so that even in the marble of the Pietà in Florence during the restoration one of these microfractures appeared, and in that of the Moses an evident small crack starts from the coat and crosses the right knee.

In his studio in via Mozza in Florence, Michelangelo, assisted by the Maestro Domenico di Giovanni di Bertino from Settignano called Topolino, continued the working of the marble for the facade. The foundations of the new facade where also carried out.

But in 1519-1520 the work on the facade was blocked: the pope no longer seemed interested, or perhaps also because of the lack of money (Vasari). Between February and March 1520 the contract was cancelled: Michelangelo was embittered, also because the real reason for the blocking of the works had not been told to him, and he writes that because of the infinite displacements for Carrara and Pietrasanta … I was on horseback eight months …

The marbles still in the quarries where purchased in part from Sansovino, in part they where sent to Naples for Vittorio Ghiberti (son of Lorenzo Ghiberti).

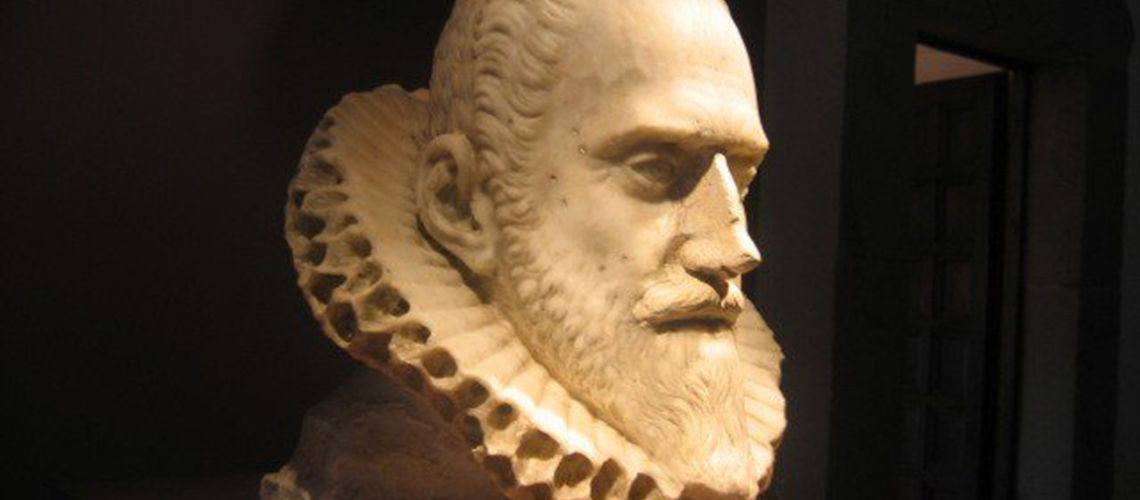

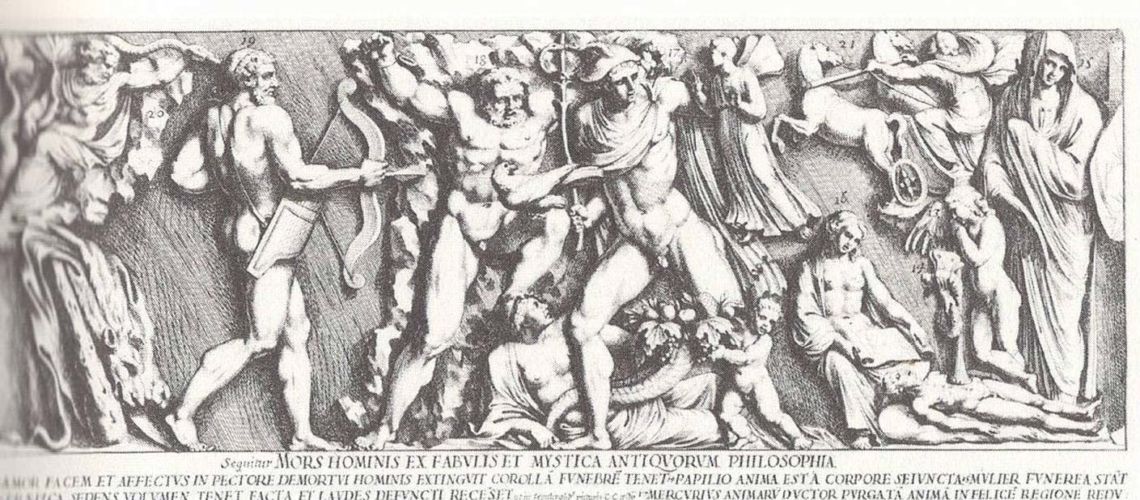

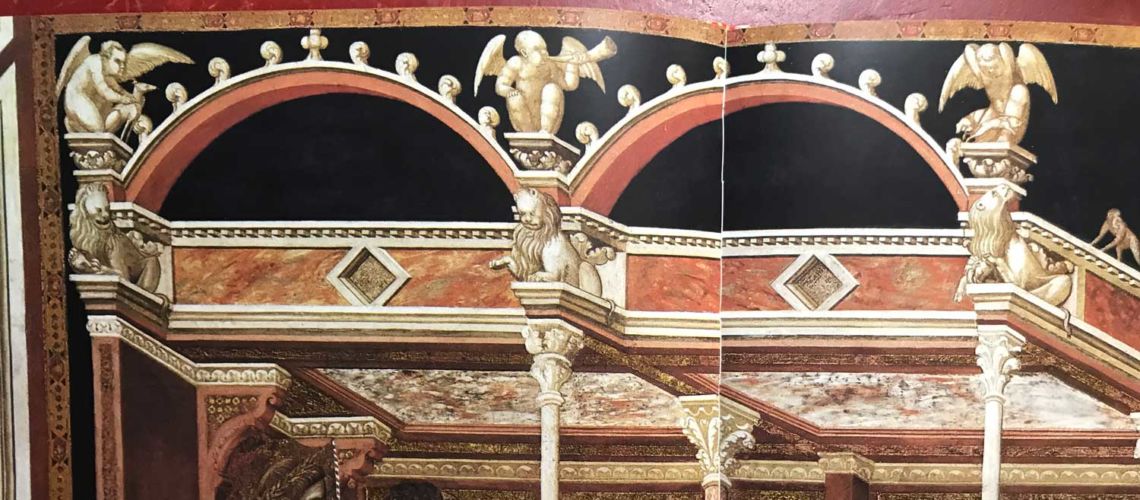

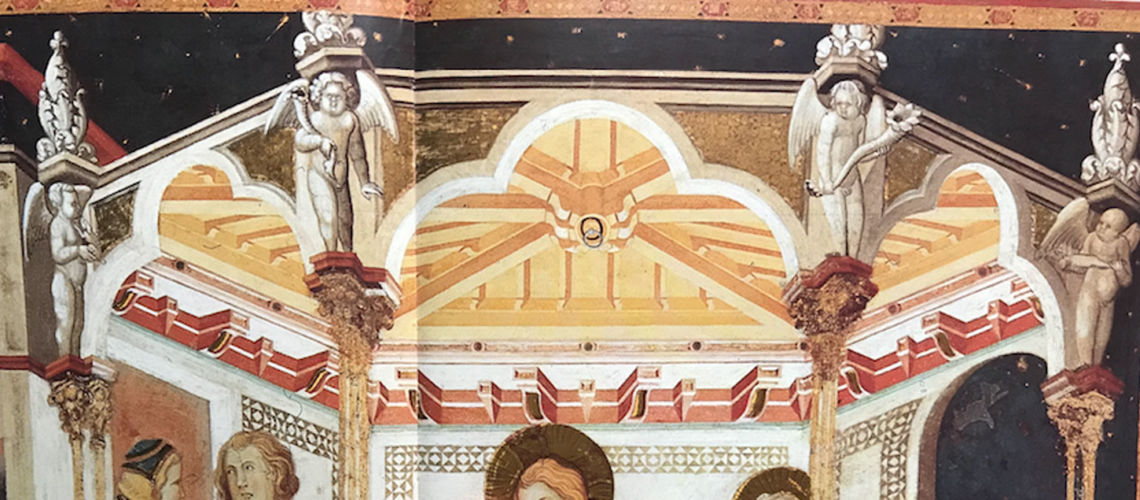

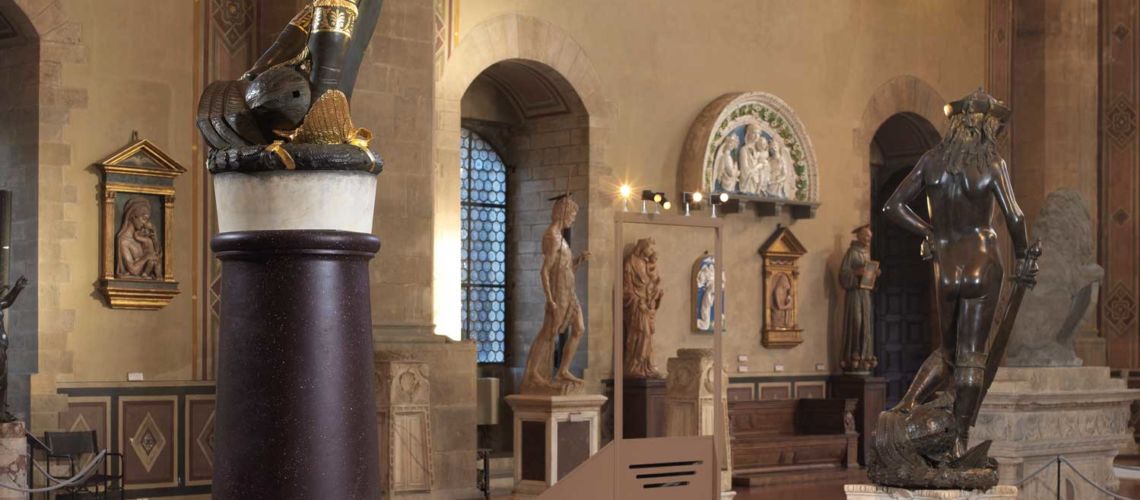

But soon Michelangelo was heartened: he received from Giulio dei Medici, the future Pope Clement VII, the task of designing the New Sacristy in San Lorenzo, to place the tombs of Lorenzo the Magnificent and his brother Giuliano, of Lorenzo duke of Urbino (seventh son of Lorenzo the Magnificent), and Giuliano Duke of Nemours (grandson of Lorenzo the Magnificent).

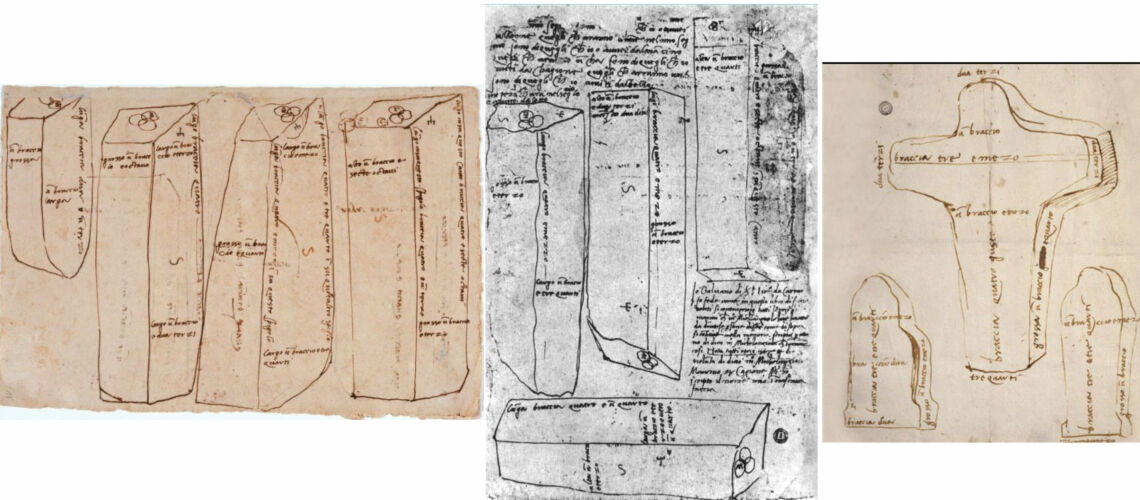

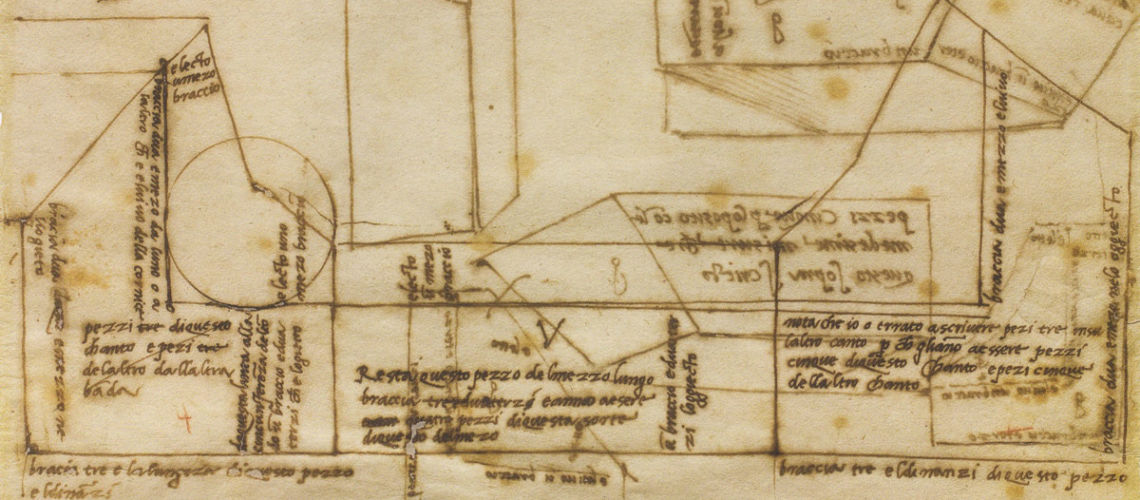

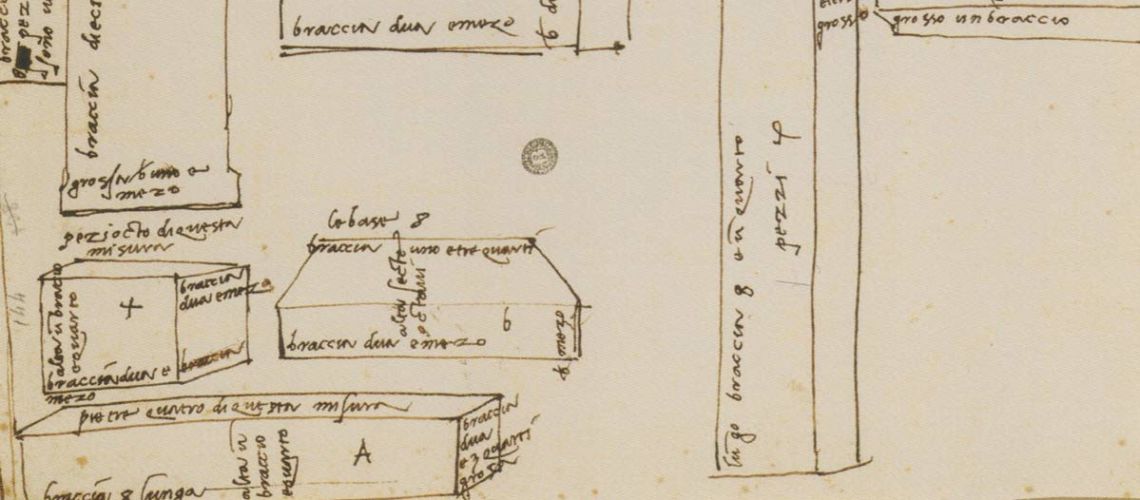

In 1521 he received 200 ducats from Cardinal Giulio and on 9 April he returned to Carrara to order the marbles for the tombs of the New Sacristy. He stayed there for about 20 days making the measurements of the burials and drawing them. He returned to the house of the quarryman Francesco Pelliccia, as usual in Carrara, ordered 200 cartloads of marble specified on the notary contract which he stipulated on April 23 with the quarrymen Pollina, Leone and Bello. On April 2, he signed another contract for 100 cartloads of marble with the quarrymen Marcuccio and Francione del Ferraro.

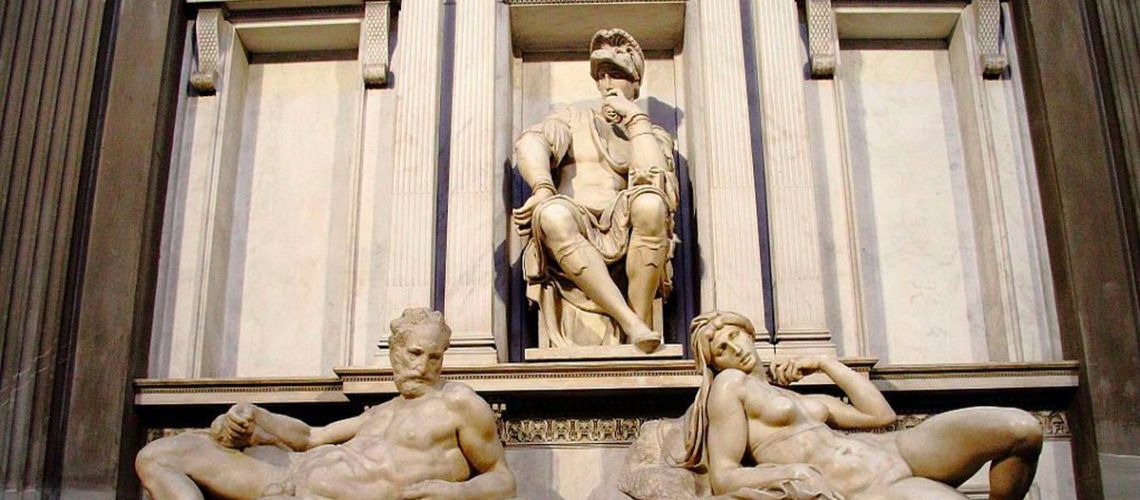

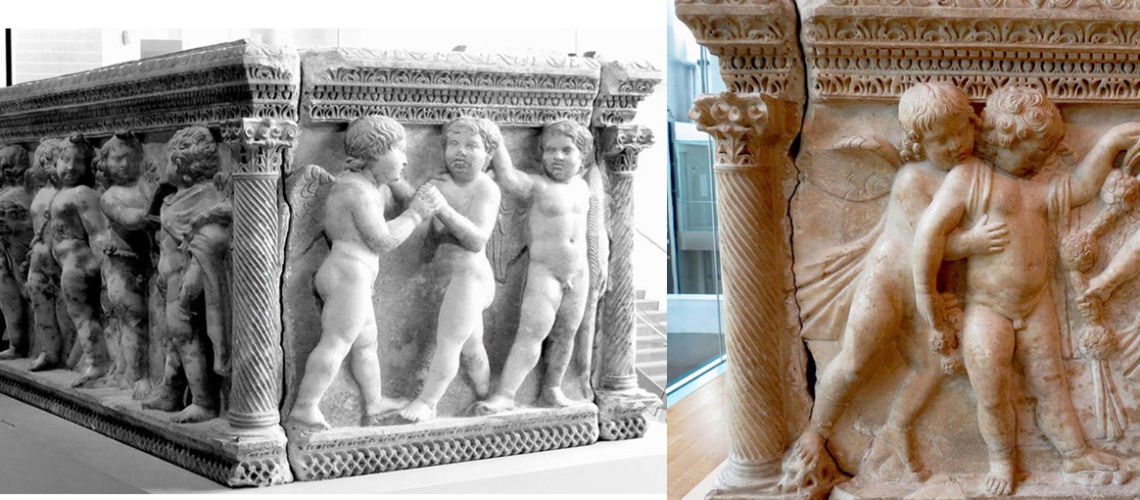

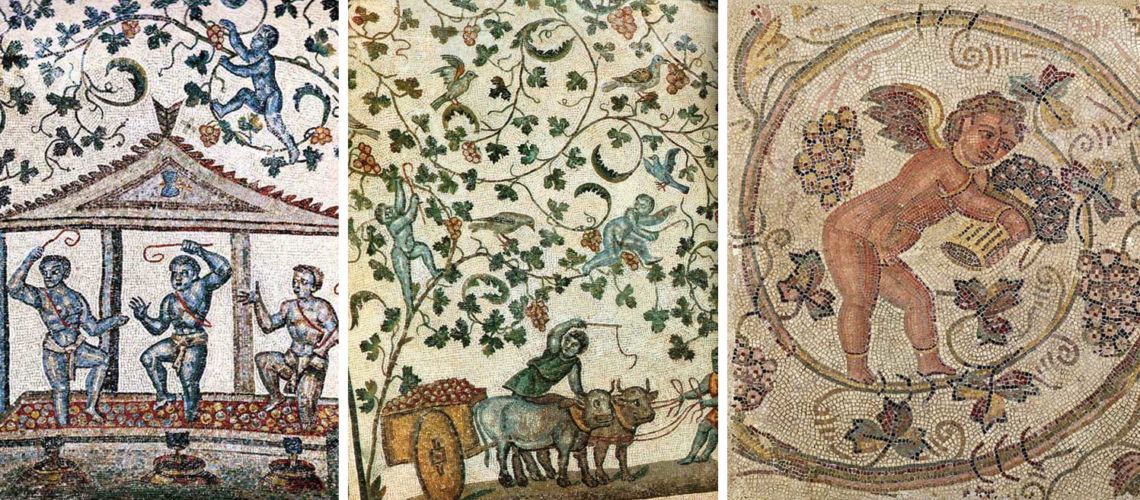

Since 1520 Michelangelo had designed various plans for the tombs, which he discussed with Cardinal Giulio. In 1524 he had created the definitive models that he began to sculpt. In 1526 the first tomb was walled in the chapel, that of Lorenzo Duke of Urbino with the statue of Lorenzo posing as a thinker and allegories of Aurora and Twilight.

Subsequently he sculpted, with the help of Montorsoli, that of Giuliano Duke of Nemours with allegories of Night and Day.

The events relating to the supply of marble from Carrara become tangled and complex, Michelangelo returned several times to Carrara, but was too busy in Florence and leaved his seconds to manage the extractions. But the work on the New Sacristy went on.

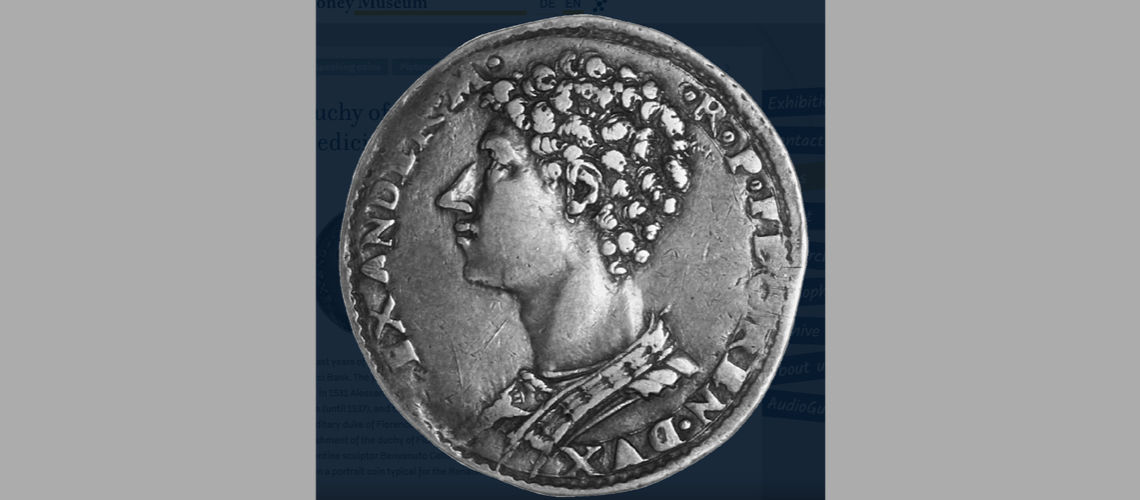

In 1527 following the crisis between Pope Clement VII of the Medici family and Emperor Charles V of Habsburg, the Florentine people, fomented by the friar Girolamo Savonarola, expelled the Medici from Florence by establishing a republican government. Michelangelo collaborated with the new government taking care of the fortifications. In 1530 Florence was besieged and surrendered in 1532, the republican government was replaced by the Medici lordship of Alessandro dei Medici, illegitimate son of Pope Clement VII.

On the return of the Medici, Michelangelo resumed work on the New Sacristy which continued until 1534, the year in which he went to Rome to fresco the Sistine Chapel.